Why did you want to make a ballet about Anna Pavlova?

I love celebrating people who did extraordinary things in dance. So when the director of En Avant Dance Company in Guayaquil, Ecuador, wanted to work with me, I went to my folder and asked: what happened in Latin America related to dance? Who needs to be celebrated? Anna Pavlova was a pioneer, and actually performed in Guayaquil in 1917. It was a new ballet, so we needed to do a lot of audience development – but a challenge always makes me excited.

How do you reimagine Pavlova on stage?

How can you sum up a whole life and honour her legacy, in just an hour and a half? I work with an extraordinary writer and dramaturg, Ignacio Vleming. It was an 11-month process of development, and before that, all the research. You need to go into the archives, as I did at the Royal Academy of Dance. I analysed her body language in images and also in recordings held at the British Film Institute in London. She develops as a Russian prima ballerina but becomes aware that she can impact people. At the end of the day, you need to make her human and approachable.

Pavlova belonged to the Belle Époque: the moment when fashion, photography and cinema all started. She was very connected with what was happening: she always wanted to be photographed, and developed her own posing style. Diaghilev didn’t allow his productions to be filmed, but she did. She embraced new technologies, which was very exciting.

‘The RAD were very keen to share everything. I recommend everyone to go there’

How did visiting the RAD archive help?

The RAD has lots of magazines that talk about Pavlova, lots of photographs that I hadn’t seen. There are even some items that she owned, like a little figurine that she crafted herself and a scarf she wore. I even found an article that she wrote about pointe shoes. She says that using pointe shoes is a sacrifice, but also gets you close to something mystical. That’s the only text that we have from her.

The RAD were very keen to share everything with me. I recommend everyone to go there, they have a lot of things for anyone that wants to develop choreography. Until I did this research, I didn’t feel there was a space for me in the RAD, as a choreographer. But when I started to use the archive and library, I felt there is more room for members like me.

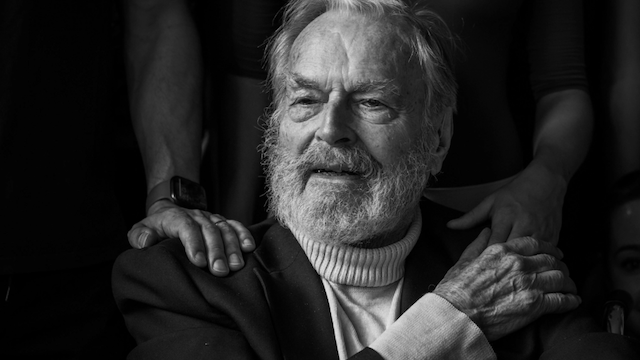

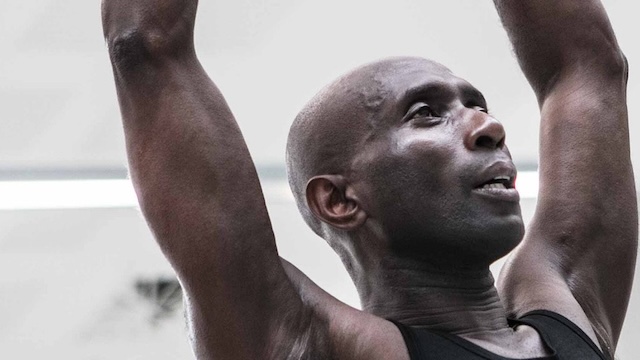

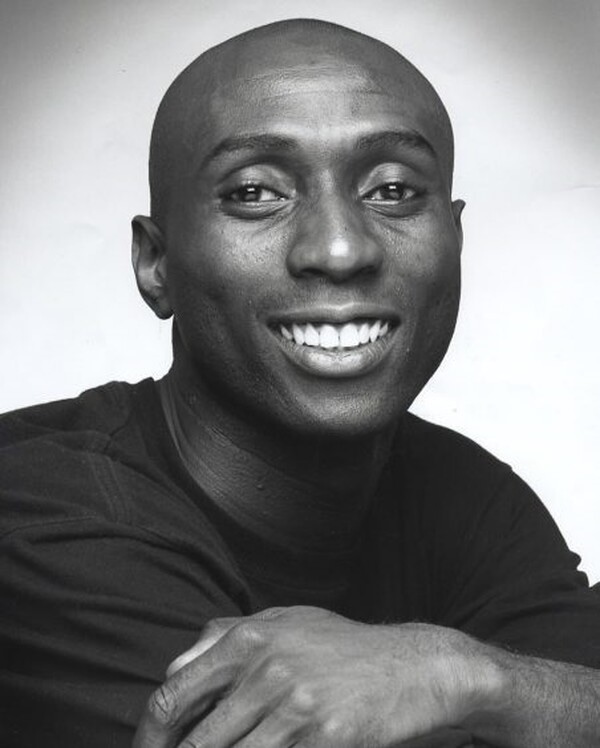

What connects your work as a performer, choreographer and mentor?

What connects is my love for dance, but also for the people that dedicate their lives to dance. I’ve travelled a lot and seen the difficulties that women and girls especially have to develop their creativity. So my work always tries to celebrate women and girls. In my tiny world, I’m hoping that I’ll help them to achieve their dreams.

How did your dance journey begin?

My parents loved to dance – in Spain, people dance all the time – but I was shy. When I was seven, a friend of mine was going to ballet. I didn’t know what that was, but gave it a try. I loved the fact that I was connecting to myself with my body. It was something that I hadn’t experienced before. I trained in Mallorca, but also went to Madrid to study Hispanic philology and linguistics. A tumour in my leg stopped my dream of becoming a ballet dancer, so I went on to tango and then contemporary dance. I could tell things in my own way, which was mind-blowing: I can be myself!

Having an independent company is, as you can imagine, challenging on every level – you don’t have the same resources as a big company. But it is like a laboratory. You can experiment. You can try ideas. You can progress your art, your vision – have flexible creativity. I also make a conscious effort to overcome my Eurocentrism by collaborating with other artists. I went to the North Pole to work with the Inuit at minus 40. I’ve been in Patagonia, Burkina Faso, Senegal and Taiwan, working with pioneering artists whose work deserves to be seen.

What makes a good teacher?

Generosity. You need to find a generous teacher who will offer you the best approach according to your needs: your physical and mental condition, your emotional context. That takes a lot of work from teachers.

Creating a no blame environment in the space is also important. A good teacher should be happy to be challenged. Pavlova was actually a very good teacher. Her dancers said how generous and humble she was – but at the same time she changed the lives of so many people.

Watch

Trailer for La Pavlova