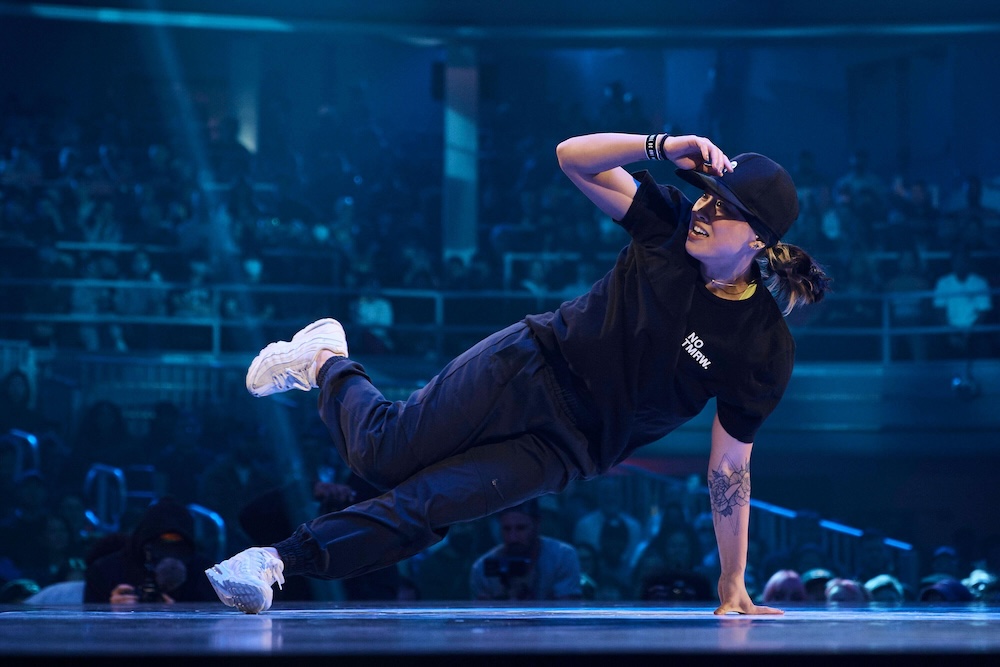

The setup is unlike any other Olympic event before it.

A DJ spins their tracks while the MC encourages the crowd to vibe to the beat. Competitors bop and stalk around a stage, twisting their bodies, shuffling their feet, flipping into the air, freezing instantly, contorting their arms, and boasting in their opponents’ faces throughout a spontaneous one-on-one dance battle.

This is what the scene will look like in Paris on 9 and 10 August, when breaking (don’t call it ‘breakdancing’!) will feature at the 2024 Summer Olympic Games, signifying its official debut on the world’s biggest stage. Over those two days, 16 b-boys and 16 b-girls will compete to become breaking’s first-ever Olympic champions. For many members of the breaking community, the Paris Games will be a coronating moment. For others more leery, an iffy rendition of what they consider their way of life.

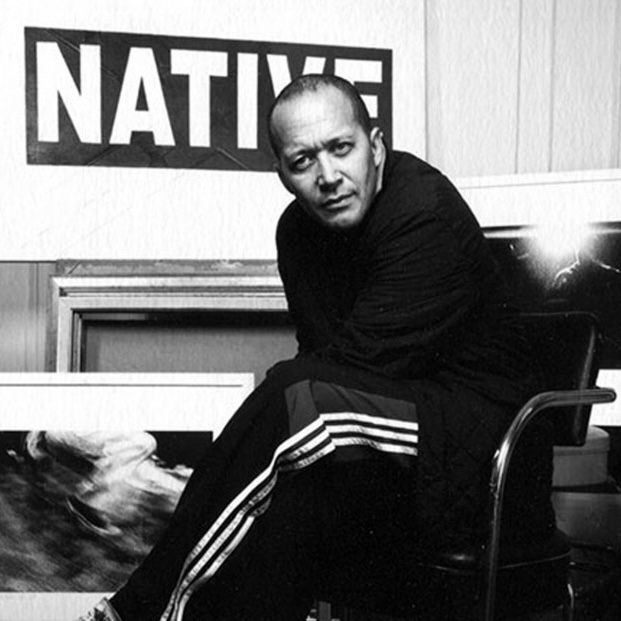

Breaking’s presence has spread out to the streets of Europe and Asia from the Bronx. Ken Swift’s breaking education began on 99th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, in the Upper West Side projects of Manhattan, during the late 1970s. Just an adolescent, Swift (born Kenneth Gabbert) observed Black and Puerto Rican kids breaking in parks as the hip-hop movement swept through New York City, inspiring rappers, poets and other creatives. ‘Breaking is the first dance of hip-hop culture,’ says Swift, one of breaking’s foremost figures as a longtime member of Rock Steady Crew. ‘It’s the dance that stood the test of time and is still here.’

Now, breaking is the first dance sport discipline to be included in the Olympics. It is one of four ‘new’ events (along with sport climbing, skateboarding, and surfing) in Paris 2024, in tandem with 41 established sports.

Starting with the Tokyo 2020 Games, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has allowed host cities’ Organising Committees to propose events for their specific Games. They can include events the IOC believes will fit their hosts’ vision, intending to showcase and reach younger, diverse athletes and audiences. (For example, Los Angeles 2028 will include five new sports: baseball/softball, lacrosse, cricket, flag football and squash.)

Several years of effort culminated in breaking getting into the 2024 Olympics. Breaking’s popularity first peaked in the 1980s, with some seeking to make it mainstream. (Think Flashdance.) Swift, by then a chief member of Rock Steady, remembers battling the New York City Breakers, who wore matching ‘really tight’ bobsled suits. ‘We’re on the other side, we’re laughing,’ Swift says. ‘We’re like, “Yo, y’all look stupid, man! Like, this is not the style. That’s not how you dress. Dress fresh!” But they were pushing in that direction.’

Michael Holman, the Breakers’ manager, had the idea of putting them in matching outfits. The Breakers were among the first crews to earn widespread notoriety, performing on NBC’s The Stars Salute the US Olympic Team in 1984. ‘Backstage, I was thinking: why are we entertainment?’ Holman says. ‘Why aren’t the breakers themselves Olympic athletes?’’

Holman wrote a proposal calling for breaking to be an Olympic sport, including draft rules and structure for a potential competition. The Breakers all signed it. ‘We, the New York City Breakers, see the Olympic games as our future,’ it said. ‘We see breakdancing as a future. We see breakdancing as a future Olympic sport, and ourselves as pioneers in making this dream a reality.’

‘People at that time saw that proclamation about breaking being an Olympic sport as just a pipe dream,’ Holman says. ‘That was wishful thinking. I wanted that to happen, but I never believed it would.’ He lobbied, but to no avail. Breaking lost some of its momentum entering the 1990s – before Swift and other second-generation breakers helped elevate it back into the spotlight, with judged competitions propelling it forward.

In the 2010s, however, another visionary took up the dream of getting breaking into the Olympics. Jean-Laurent Bourquin served as a senior advisor to the World DanceSport Federation (WDSF), recognised as the global governing body for dancesport disciplines since 1957. After 17 years working with the IOC, Bourquin joined WDSF in 2016, as it sought to get a dancing discipline into the Olympics for the first time.

The WDSF executive board told Bourquin that it wanted to lobby for ballroom dancing. Instead, Bourquin suggested breaking – initially, there was pushback. In April 2016, Bourquin spoke with members of the IOC and suggested implementing breaking at the Olympics. In June that year, he presented the idea to the WDSF board at an assembly in Rome, urging confidentiality so he could get all necessary parties – the IOC, the WDSF and, crucially, members of the breaking community – on the same page.

Getting the backing of major players in the breaking community proved essential. ‘This culture is very important for us to preserve,’ Swift says. ‘Because there are things that destroy and confuse people in the world, especially with hip-hop culture.’

‘I don’t feel like breaking is a sport. This is a dance form. It’s an art’

Ken Swift

Many voices in the breaking community argued that breaking isn’t a sport and shouldn’t be overseen by a governing body. ‘There’s something that’s breaking did for me that was completely different,’ Swift says. ‘It involves the connection to rhythms and drums and beats. And it’s something that’s deeper – I just don’t feel like it’s a sport. People don’t play basketball to the beat. I don’t “play” breaking, you know? This is a dance form. It’s an art. And it’s based upon the music.’

In December 2016, the IOC officially announced that breaking would be added to the 2018 Youth Olympic Games in Buenos Aires. The trial run proved a huge success. Behind the scenes, Bourquin continued working to get key influencers, like Niels ‘Storm’ Robitzky and private equity executive (and former breaker) Steve Graham, on board with his Olympic vision, including how to judge the competition, while expressing respect for breaking culture.

‘I said: “Guys, don’t worry! Breaking will be presented in the Olympic Games in its full authenticity,”’ Bourquin recalls. ‘We will not change breaking in order to make it Olympic compliant. The IOC has to accept the breaking as it is as a culture and we have to work with a community.’ And on 6 December 2020, the IOC confirmed breaking would feature at Paris 2024.

In Paris, nine judges from nine different countries will assess one-on-one battles where each breaker gets three turns to perform, known as a throwdown. Breakers are judged on six criteria: creativity, personality, technique, variety, performativity and musicality. Judges will use a digital scoring platform called Trivium to judge physical, artistic and interpretative qualities of routines. It’s a subjective process, but a sizable difference from how winners were originally determined.

‘Look at the ways they’re training. Strength, toning, flipping – there’s a lot involved’

Whitney Carter

Three basic elements make up breaking: top rock (moves performed while standing), down rock (performed on the ground) and freezes (standstill positions). Flashier are the power moves (where breakers spin their whole body on their hands, elbows, back, head or shoulders) and flares (where breakers are on the ground and swing their legs underneath).

If performances are equal, Swift suggests, judging could come down to demeanour and delivery. ‘As my boy Doze [Green, formerly of Rock Steady Crew] used to say: “In hip-hop culture, style defeats technique every time,”’ he says. ‘Because it’s the individual, it’s the person.’

Whitney Carter, Team USA’s Director of Internally Managed Sports, says that she’s been very impressed by the American breakers. ‘You look at some of the ways they’re training,’ Carter says, ‘it’s strength, it’s toning, it’s flipping and dancing and timing and mentally, there’s a lot involved.’

Despite the United States being the birthplace of breaking, it won’t feature in Los Angeles, but those invested believe that it could return to future Olympics. ‘This is the power of the Olympic Games: it touches everybody around the planet,’ says Bourquin, who left WDSF to start a sports advisory service in 2021. ‘So I’m very happy that people who will be 50 in 2050 will say, “Ah, it was great when breaking was in Paris 2024!”’

Even members of the older guard who are more protective of the culture’s ethos have a respect for seeing breaking on the Olympic stage. Swift, for his part, thinks ‘it’s dope.’

‘If a young person wants a gold medal, and that’s his or her drive, that’s everything,’ Swift says. ‘That’s priceless. It’s hard to be inspired in this world right now – there’s a lot going on. And if a young person has an inspiration for art, I’m down with that.’

WATCH

The French breaking team prepare for Paris

Kaelen Jones is a sportswriter and host of History Channel’s Sports History This Week podcast.