It’s 2013, and in a packed Jamsil Arena in Seoul, 5,000 fans encircle a small stage that’s about to see a battle between two hometown favourites. The Red Bull BC One Finals, the largest one-on-one competition in the b-boying world, was being hosted in South Korea for the first time. After nine months of battles among 2,000 b-boys from 53 countries, two Korean dancers, Hong 10 and Wing, were among just four to make it to the semi-finals. Both had won the event in the past; the winner of this bout would become only the second-ever b-boy to be crowned a two-time champion.

The two dancers wear Red Bull logo t-shirts, black khakis and Nike shoes. Wing sports a bright red flat cap with flower prints. As the DJ starts to break to a looping hip-hop track with an intense drum solo that blares and echoes throughout the arena, the rivals share a staredown: it’s often strategic to go second in a battle. The two have trained and toured the world together since they were a part of South Korea’s breakdancing heyday in the early 2000s, when the nation’s b-boy crews started to dominate international competitions traditionally won by Americans and Europeans. Wing eventually gives in and jumps to centre stage first as a sign of respect to his senior of one year – as is expected in conservative South Korea.

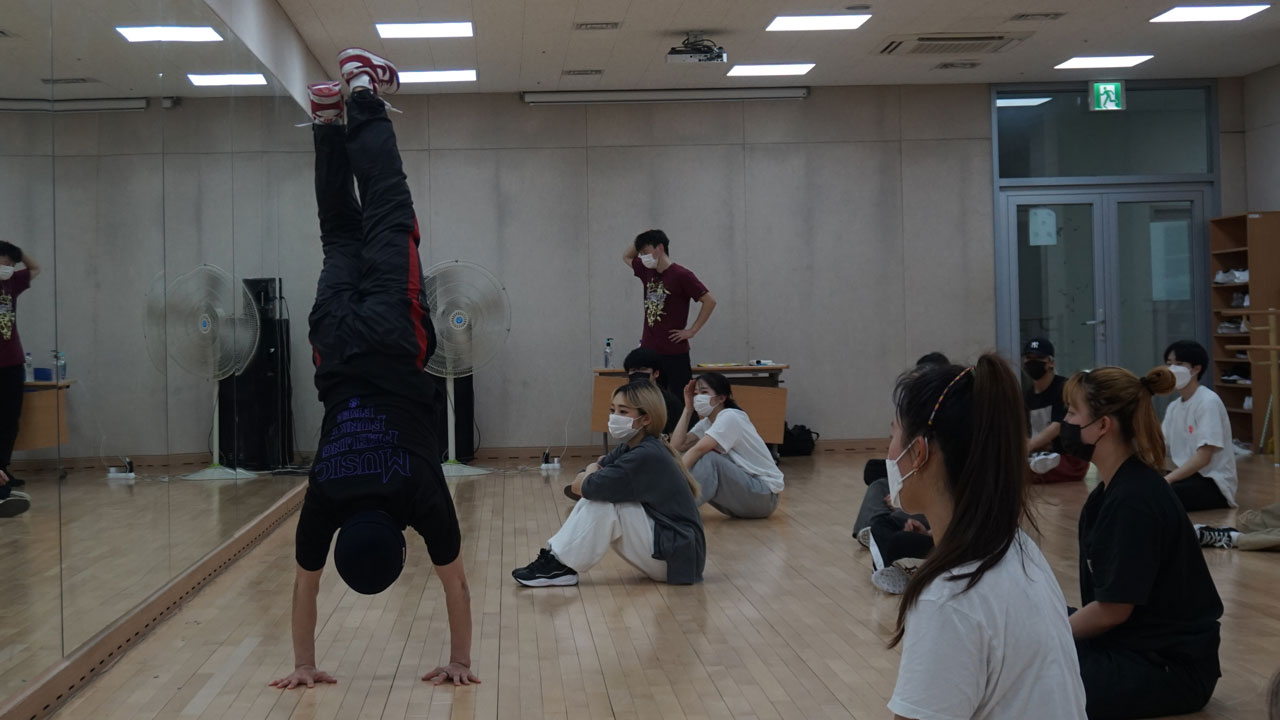

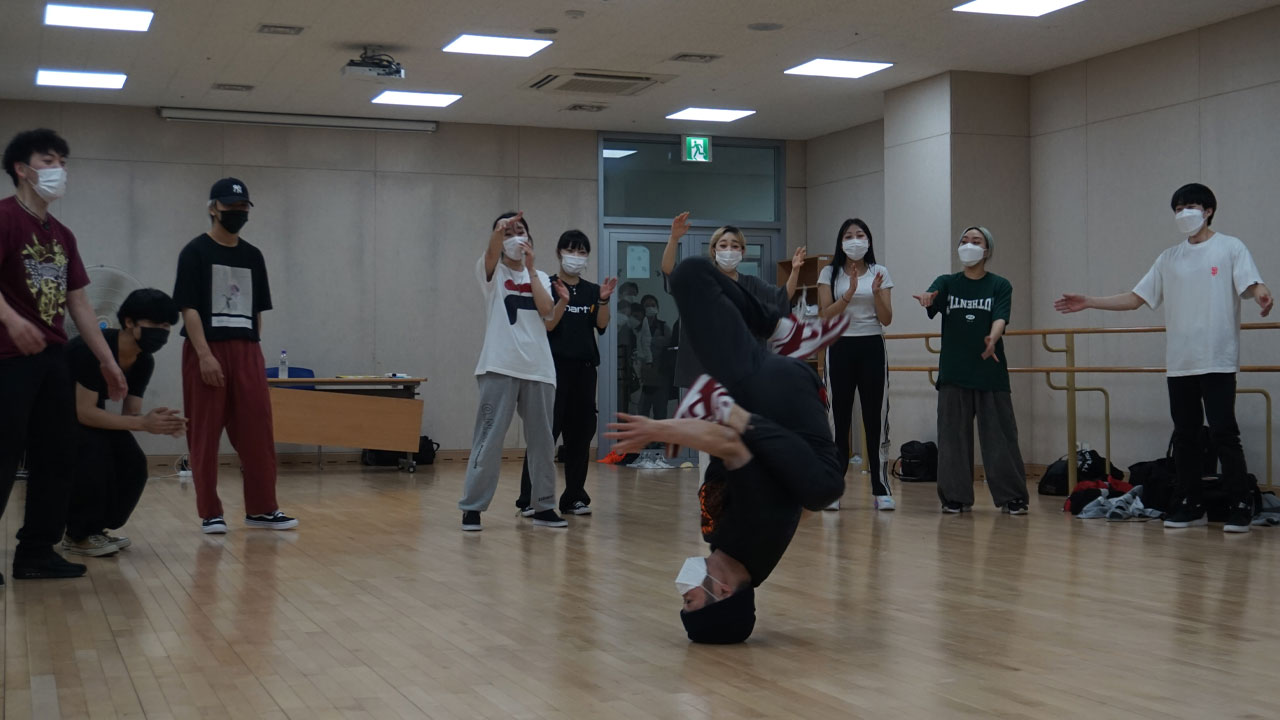

The contenders take turns stepping to the rhythm, spinning on headstands and handstands, and freezing in the most contorted positions imaginable. While each awaits his turn, he constantly throws playful gestures and fierce gazes at his opponent. Hong 10 wins the three-minute battle – he would also end up getting his second champion’s belt in an event watched by hundreds of thousands around the world.

Now, nearly eight years on, the International Olympic Committee has announced that breakdancing – a term the b-boying community does not welcome – will make its debut at the 2024 Paris Games. Many South Korean breakers are filled with anticipation about winning a medal representing their country.

It’s still unclear if the Olympics will hold a crew-orientated tournament, as in most international b-boying events, or if there will be only individual categories. Either way, Kim Hong-yul (Hong 10’s real name) expects to be a part of the national team. That famous run at Jamsil Arena cemented his legacy as one of the most successful and decorated b-boys the world had seen – and the 36-year-old veteran is hungry to prove that he is still at the top of the game: he is currently ranked third in the world by Bboyrankingz.com. ‘I exercise regularly at home and practice about five hours a day in the studio,’ he says. ‘I didn’t know before, but this is not a given for many b-boys out there.’

Wearing his signature black beanie, Kim and his crew enter a cafe in a crowded alleyway in Hongdae and blend into the trendy Seoul neighbourhood. However, abroad he is often approached for photos and autographs by fans who have been following him over the past two decades.

Last year, he formed Flowxl with longtime friend Shin Kwang-hyun (B-boy Rookie), who shared a vision of ‘making bigger stages.’ Both were members of Expression Crew in 2002 when they became the first South Korean crew to win Battle of the Year, known as the ‘world cup of b-boying.’ But they wanted more. While their first official performance was at a church in Seoul earlier this year, Flowxl plans to continue collaborating in music, fashion and religion to change how street culture has traditionally been seen in South Korea.

Despite South Korean success in the field, a new generation of world-class b-boys hasn’t yet followed those that paved the way. Despite his victories, people have told Kim to get a ‘proper job’ and to quit before his body deteriorated from breaking. However, Kim is already looking ahead to his fifties and he says he will still be a b-boy.

‘I think highly of b-boys and b-girls. They’re so cool and fresh,’ he says. ‘So I want to change the perception that b-boys don’t think straight, can’t make a living and only make their parents worry. I hope I see the day when people view b-boying as cool, just as they would any other sport or hobby.’

‘When people ask me how much b-boys make,

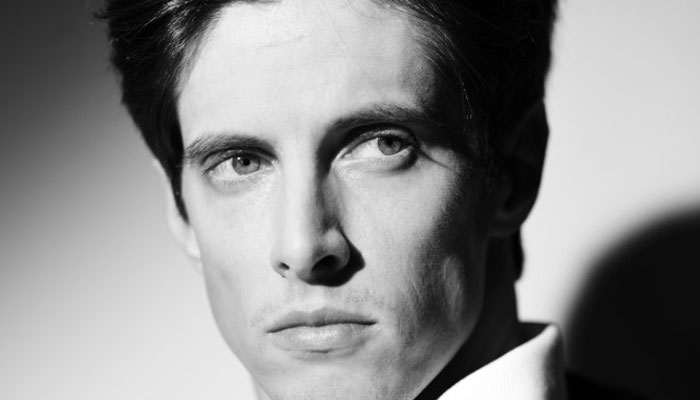

Chung Hyung-sik

I tell them to find another job’

For another pioneer of the South Korean scene, providing guidance to young breakers has become a career following competitive breaking. Inside a quiet college campus, fast-paced music and excited howls emerge from downstairs in one of the buildings. In a mirrored room, 20 students make a circle around a man in track pants and a beanie. This is Chung Hyung-sik, better known as B-boy Sick, and he was showing his class at Sejong University in Seoul that he too once stood head-to-head with b-boys like Hong 10. He is a part of the legendary Gamblerz Crew that stacked up more than 50 wins in international competitions after making their name worldwide in 2002.

‘When I first started, there weren’t a lot of older b-boys who would show us the ropes,’ he says. ‘The competition was so fierce that the only thing I learned was to step over competitors in order to climb to the top. It was total survival mode back then.’

He found early in his career that he had a knack for teaching when he helped fellow crew members in international competitions. He hosted workshops and was eventually scouted by the university to teach breaking. ‘Our philosophy here is to try to get students to like b-boying rather than trying to make them elite b-boys,’ he says. Most of his students take it as an extracurricular class.

‘I think there was a fallout in the South Korean b-boy scene because we failed to make it attractive to newcomers,’ Chung says. ‘Instead of harboring an environment that made b-boying fun, the country’s tendency of cramming education so one can “be good” made it unenjoyable for young dancers.’

Extreme competitiveness has brought success, but it’s also this mindset of only striving for first place that makes South Korean parents send their children to crammer schools rather than dance academies once the school day ends. ‘The Olympics can only do so much for our scene,’ Chung says. ‘We need a restructuring of our system that cultivates b-boying as a culture before focusing on competition.’

He remembers visiting dance studios with his friends after school in his hometown of Busan, when he first fell in love with breaking. ‘In these community centres and youth facilities I would meet up with other kids and form crews,’ he says. ‘There’s no space to practice these days for young people just starting out, as dance studios and community centres have started to charge fees or have limited access. Ultimately, we need the country to back us up through funding.’

At one time Chung and Gamblerz Crew made frequent TV appearances. ‘But the hype around our country’s b-boys eventually faded away, and many resorted to part-time jobs to make up their living.’ B-boys who are part of named crews can offer lessons, appear in music videos or on stage and take other freelance work. ‘When people ask me how much b-boys make, I tell them to find another job,’ Chung says. ‘This profession is for people who enjoy the culture. But it’s possible to make enough to get by if you work hard enough.’

‘I often think about how good it would’ve

Sho Youn Kyoung

been if I knew how to break as a kid’

This is why b-boys are mapping out different business ideas. Jinjo Crew, South Korea’s top team, started a YouTube channel and Expression Crew toured internationally with their musical Marionette, incorporating breakdance with elements of modern dance. Other b-boys are returning to school to get degrees and elevate their dance repertoire. ‘Some are now looking for new ways to generate revenue such as participating in educational enterprises sponsored by local governments,’ Chung says.

He also thinks there has been major progress for women in the scene. ‘The women have started to change the perception around b-girls,’ he says. ‘The energy and dynamics of some of the top b-girls have made their performances catch up to the men in some ways.’ However, due to the lack of opportunities for women to earn a stable income, there haven’t been significant changes in participation. In the past two years, Chung estimates he has only seen three female students enrol as a b-girl major.

B-girls like Yell, a member of Gamblerz Crew, prove that women can succeed in street dance. In addition to being a junior Olympic champion, she is also a choreographer for YGX, one of the country’s biggest entertainment academies, and is sponsored by Nike.

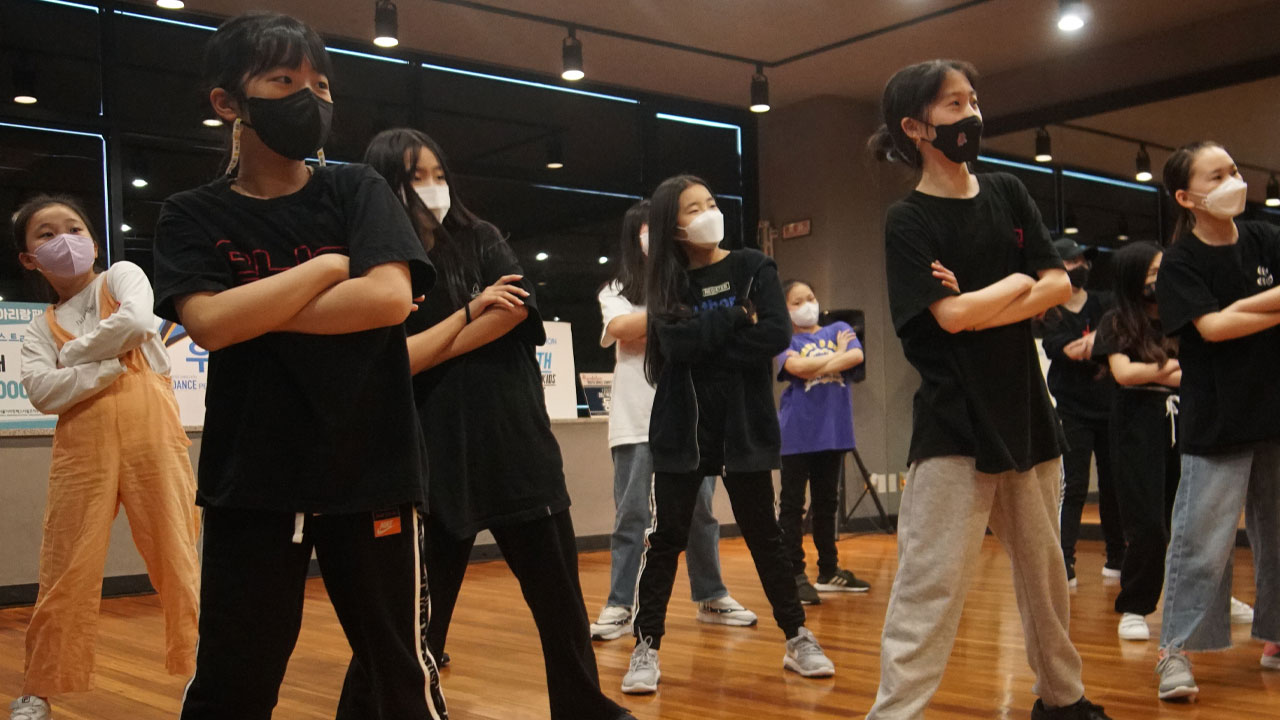

In the city of Paju, north of Seoul, girls in their early teens chat excitedly in a small dance studio with shiny wooden floors and flashy lighting. K-pop plays in the room next door. There is only one breakdance class a week, but Sho Youn Kyoung, the academy’s director, considers this a huge advance. ‘We didn’t start out with a b-boying class as parents view breaking as a dangerous dance and there was no interest in classes,’ she says. ‘But after breaking became an Olympic event, there have been positive reactions to our new class.’

Ninety percent of students at her academy come for K-pop classes. But some of them fall for breaking after seeing instructors performing windmills and headstands. 11-year-old Kim Eun-seo started to dance at the academy two years ago when she wanted to imitate K-pop girl groups she had seen on TV. Now, her favourite class is the b-boy class on Sunday. ‘The poses that b-boys make look so cool and it’s fun to learn,’ she says. ‘I like to look up videos of b-boy Differ breaking in international competitions.’

As for her dreams, Kim wants to become a famous dancer who wins awards and becomes well-known. ‘I also thought about becoming a b-girl,’ she says. ‘I am practising how to do a windmill at home.’

Sho admits that her academy is the only place in Paju that offers breaking classes, but predicts this will soon change. ‘Parents seem to change their views about breaking as successful b-girls make their names known and as we inch closer to the Olympics,’ she says. Sho, 31, maintains that her passion for street culture – including hip-hop music and other forms of street dance – was the reason for her academy in the first place. ‘There is a reason that I like to incorporate street dance as much as we can,’ she says. ‘I want my students to grow up experiencing the street dance I fell in love with as a college student but wasn’t able to learn as a kid when there weren’t studios that taught this type of dance. I often think about how good it would’ve been if I knew how to break as a kid.’

David D Lee is a freelance reporter based in Seoul, writing for South China Morning Post, Vice Asia and others.

Jun Michael Park is a documentary photographer and filmmaker from Seoul. He contributes to the New York Times and Monocle.