REPORTS

Pressure pointe

When are you ready for your first pointe shoe? Will a ballet influencer’s advice or a cheap online shoe be safe? Alia Waheed visits the RAD to learn the dos and don’ts of a pointe shoe fitting.

Read more

Against the odds

Iran’s protest movements drew attention to the plight of young people living in a nation where dancing is banned. Sally Howard reports on the Iranians who, despite everything, continue to dance.

Read more

Bodies of work

As disabled dance artists find greater visibility, Emily May meets choreographers who are breaking down barriers for other disabled dancers – and for the dance world as a whole.

Read more

Where are the silver foxes?

Silver Swans is one of the RAD’s most popular projects, bringing women over 55 to dance. But why do so few men embrace dance as they grow older? Sanjoy Roy goes in search of the silver foxes.

Read more

Inside out

Inmates in prison can find release from their difficulties during dance workshops. Charlotte Rowles meet the artists taking dance behind bars.

Read more

Keep the faith

Alia Waheed was surprised that her daughter was often the only Muslim student at her ballet class. She explores the barriers preventing Muslim girls from enjoying ballet, and asks how religious values can fit with the demands of dance.

Read more

Take your shot

The Fonteyn famously helps dancers grow. But how can the competition share opportunities more widely? Isaac Ouro-Gnao reports on the bursaries making The Fonteyn accessible.

Read more

Breaking point

Dance features in the Olympics for the first time this summer, when breakers compete for medals in Paris. But how was breaking chosen, and what will be the impact on the art form? Kaelen Jones reports.

Read more

Think fig

Ballet, music and more are on the syllabus at the Fig Club in Erbil, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Bekir Aydoğan visits the only RAD-registered school in Iraq.

Read more

Swan songs

The RAD’s Silver Swans programme brings older students to ballet classes. As the RAD launches the next stage of the programme, Emily May meets dancers in Germany and the UK.

Read more

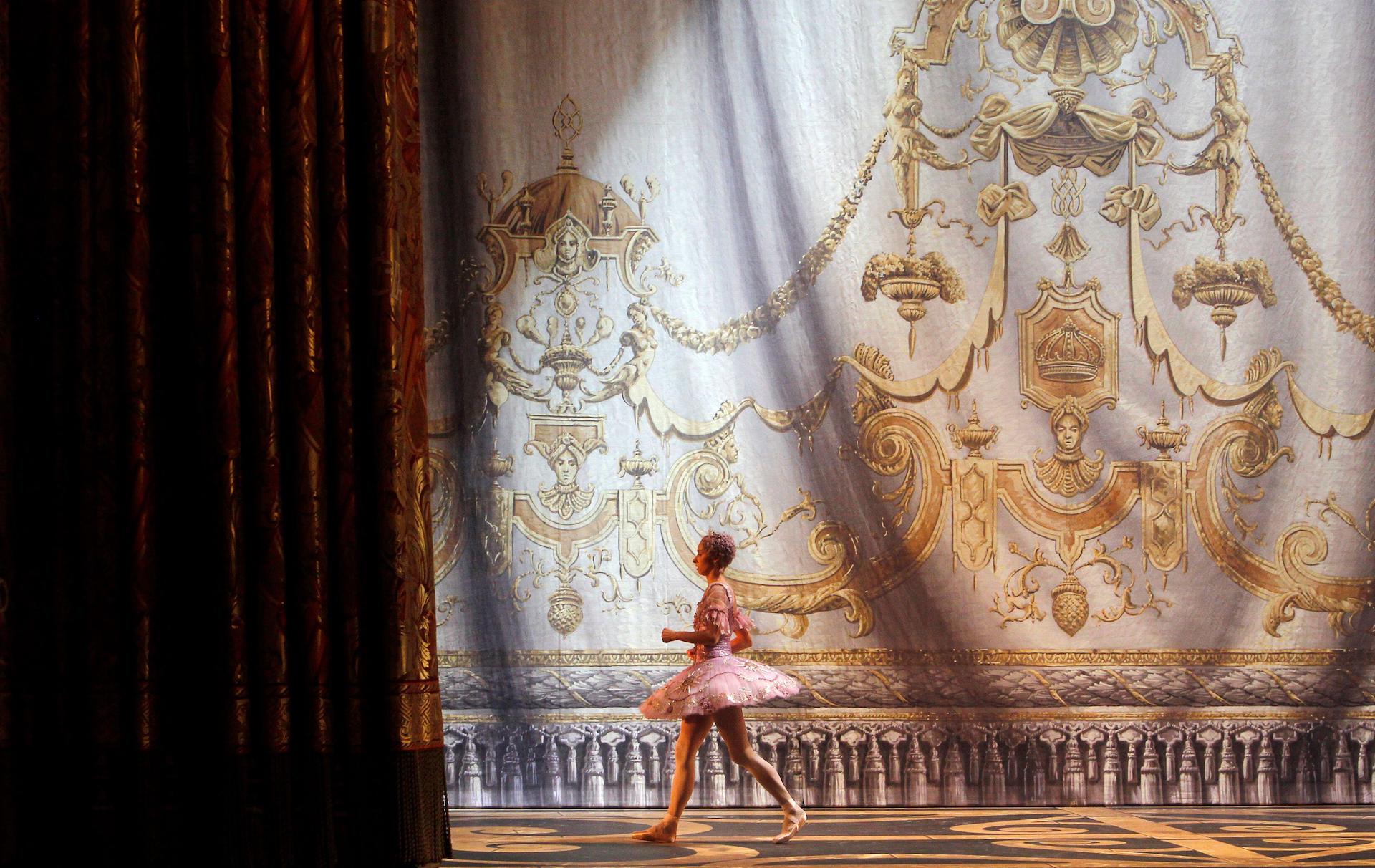

Curtain up!

The Fonteyn, the RAD’s flagship ballet competition, returns to the live stage this year. But how does it feel to be part of this cherished event? Rosemary Waugh hears from dancers, teachers and crucial figures behind the scenes.

Read more

High hopes

Ballet classes shouldn’t depend on income, says Peruvian RAD teacher Marícarmen Silva. Dan Collyns visits her school in Lima to hear about resilience and turning trash into opportunity.

Read more

Strike!

Industrial action is rare in the ballet world – but artists from Melbourne to Paris and London are protesting over pay and conditions. Jane Albert reports on what it takes for dancers to strike.

Read more

Be well

There’s a mental health crisis in the post-pandemic dance world, say RAD teachers and other dance professionals. Isaac Ouro-Gnao asks if a new focus on wellbeing can lift students and dancers struggling with their mental health?

Read more

TikTok: good for dance?

No social media platform has had a greater influence on dance than TikTok. But just how do you go viral, and is the app safe and valuable for dance? Nicolas-Tyrell Scott investigates.

Read more

‘Dance is my blood’

In Georgia, a celebrated national children’s dance company shakes off the shadow of Russia and aims to nurture national pride. Sally Howard reports from Tbilisi.

Read more

Protection programme

Dance organisations at last accept that safeguarding and child protection should be central to their work. Sally Howard reports on how the RAD is at the forefront of a slow revolution.

Read more

Curtains for the Bolshoi?

One year on from the invasion of Ukraine, Russian ballet is isolated from the wider world. Simon Morrison traces the recent history of the Bolshoi, Russia’s iconic ballet company.

Read more

Dance on prescription

Can dance help both patients and healthcare professionals? Rosemary Waugh investigates.

Read more

Where dance happens

The RAD’s new global headquarters will let the Academy spread its wings. Sarah Crompton meets the people who made it happen.

Read more

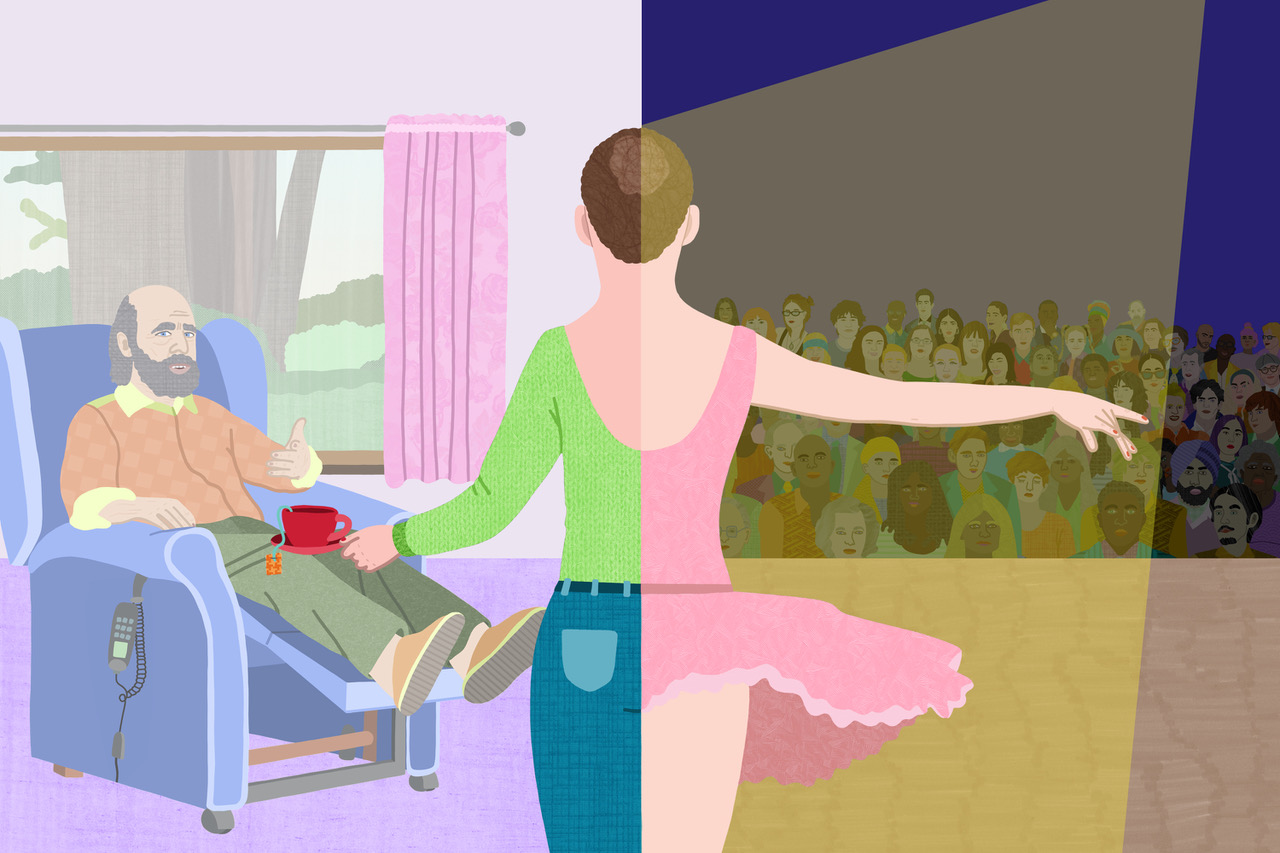

Taking care

Dance is a demanding career – especially when you also have caring responsibilities. Georgina Lawton hears about the challenges of balancing them both.

Read more

New reality

Demands on dance companies are changing rapidly, and they require new kinds of leaders. Three new directors tell Deirdre Kelly about making a difference.

Read more

Singing and dancing in the rain

Rain-drenched song and dance is a staple of Indian films. Sally Howard and Geetanjali Krishna chart the past and future of this key Bollywood motif.

Read more

Shake it up

As calls for racial equity in dance teaching grow, Isaac Ouro-Gnao asks what tangible action looks like and explores how to bring about change.

Read more

Walk tall

A migrant child crossed Europe this summer. What makes Amal unusual is that she is an 11-foot puppet who draws crowds wherever she goes. She began her journey in Turkey, where Altuğ Akin sees her welcomed by Izmir’s folk dancers.

Read more

Step change

From dancewear to touring and the RAD’s new HQ: can we dance the world greener?

Read more