A flurry of little feet and eager faces run into the bright studio, dressed in shades of pink and lilac, ready for ballet class. These are the youngest students of MyBallet Academy in east London, starting at age two. ‘She’s excited to come to ballet,’ one of the mums tells me of her daughter. ‘She even wakes up on mornings when it isn’t Saturday and says, “Is it ballet today?!”’

In the studio, RAD teacher Lydie Schrepfer gathers the girls around to sing The Wheels on the Bus. They bend their knees to show the doors of the bus opening, they ding the bell by tapping a pointed toe on the floor, they rise onto the balls of their feet to play at being mums wearing high heels, and jump and clap their hands like the children on the bus. Schrepfer then takes the children on an imaginary adventure to a toy shop where they dance through the story. One little girl who is very reluctant at the start is, by the end, twirling and marching and smiling along with the rest.

‘You have to understand: who is this little creature? How can I entice them into dance?’

Imogen Knight

Introducing the youngest children to dance might seem like play, but it’s one of the hardest jobs in dance teaching. ‘It’s very fun, but very demanding,’ says Schrepfer, author of the book Teaching Pre-School Ballet. In ballet schools it is often the younger teachers who are given the pre-school classes, says Imogen Knight, principal of Colours of Dance in Cambridge and an RAD Trustee. ‘And I think that’s the wrong way round,’ she adds, ‘because it’s much more about fundamental movement than dance movement and it takes experience to turn fundamental movement into dance.’ Schrepfer agrees. ‘If I look at myself when I was 20 years old, I was not able to do what I’m doing now,’ she says. ‘That only comes with experience.’

Not that there aren’t brilliant young teachers working with preschoolers, but the skillset needed, taking in child psychology and development, is so much broader than teaching technique. ‘You really have to understand, who is this little creature before me, and what stage are they at, and what is driving them,’ says Knight. ‘And how can I entice them into this world?’

There’s so much that young children can get out of dance classes beyond the pure pleasure of movement. ‘We’ve seen her confidence grow tenfold,’ says one of the parents at MyBallet of her three-year-old. ‘It’s also helped her posture a lot.’ There are skills to be nurtured in attention, listening, turn-taking, physical development and love of music, as well as new friends to be made. ‘It isn’t just dance, it’s socialisation, it’s separation,’ says Knight, noting that for some children this might be their first experience of a class dynamic.

For all the things dance can be for children at this age, what it isn’t is ‘ballet’. ‘We don’t call it “baby ballet”,’ says Knight, ‘It isn’t ballet until you’re about grade 1. It’s dancing.’ The RAD introduced its Dance To Your Own Tune curriculum in 2003, for ages two-and-a-half to five. It’s not a prescriptive syllabus of exercises, more a framework for learning that focuses on a child’s cognitive, motor and affective (emotional and social) development. It suggests themes and imagery to build activities around, from a secret island to an enchanted castle. ‘I like the sense that every class is an adventure,’ says Knight. Schrepfer particularly loves the music that comes with the curriculum, ‘because I didn’t want to use Disney.’

Knight agrees with Dance To Your Own Tune’s child-centred approach, involving the children in exploring each theme. ‘You might say: “we’ve landed on an island. Goodness me, there’s a turtle! Can anyone see anything else?” And that’s your child-centred cue. Somebody says something and you follow that child.’

Knight will expand on the children’s ideas. ‘You try different planes of movement – circles, random, straight lines, stopping and starting to music. You make sure you have fine motor skills as well as gross motor skills. You develop rules: no talking while the music’s playing, unless I ask you.’ Forty-five minutes goes in a flash, she says. ‘And you send them out with their neurons firing.’

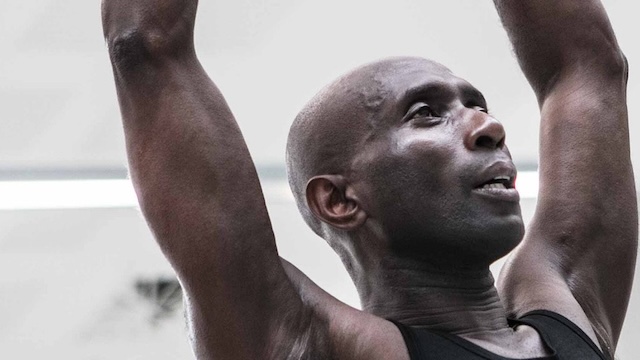

‘I got so much enjoyment from being able to create things in my own body’

Fiona Campbell

You need to have a creative mindset. ‘Not, “everyone stand up straight,” but “everyone, could you grow like a sunflower?”’ says Knight. Fiona Campbell, who runs the Wee Movers dance classes in London uses props to send imaginations in different directions. ‘Not just blowing bubbles, but imagining ourselves inside a bubble,’ she says. ‘How would that change the way we move? We’re encouraging them to think about different movement dynamics. Then how our emotions might change the way we move – things that a child might not be able to explain in words, but they can show you.’

As important as creativity is organisation, says Schrepfer, and perhaps most important, ‘you have to be fully present.’ I see in Schrepfer’s class how she pre-empts a distracted child by asking her a question and involving her in the story. ‘One good way of avoiding children not listening is to listen to them,’ says Schrepfer.

When Campbell launched Wee Movers, she wanted to create something different to her own early training. Her classes are rooted in contemporary dance, something Campbell didn’t discover till her late teens. ‘I remember just getting so much enjoyment from being able to create things in my own body, it felt so satisfying. My childhood training was very concerned with aesthetics and right and wrong,’ she says. ‘What if we flipped it round and started from this place of enjoyment, creation, imagery and ideas, and asking kids to explore that?’ Children’s creativity is central, and the students choreograph their own performances – with Campbell’s guidance, and sometimes working with visiting choreographers.

Campbell founded her school after taking her own daughter to a more formal baby ballet class where parents sat at the side, and she remembers the adults’ discomfort when their children didn’t do as they were asked. Her answer was for the parents of the youngest two-to-three-year-olds to join in too: you all dance together. ‘They settle into the environment quicker, so you get more out of them,’ she says. (Full disclosure, I attended these classes with my own son when he was small and it was a tonic to joyfully move to music on a Saturday morning.) Unlike many dance schools, Campbell has lots of boys in her classes, a roughly 50/50 split in the early years, and the content, language and branding lean away from gender stereotypes (there’s no uniform either).

Childhood has changed since Knight was young. ‘When I grew up we were quite feral,’ she says. ‘Go outside, come back when you’re hungry.’ Children’s lives are much more managed now, often for valid reasons, ‘but that means children are often frightened to do something in case it’s wrong.’ Some children are cautious and need to watch something before they try it, she says. Others will be neurodiverse and may be sensitive to choices of music. Knight has a soft toy, Miss Minnie, that children can hold if it helps them feel secure.

‘Success is participation,’ says Knight, with the caveat that you will never achieve that 100% of the time. Schrepfer suggests not holding the reins too tight. She doesn’t put small children in lines, for example – they can find their own space. But that doesn’t mean a lack of discipline. You need boundaries in place, something not all children are used to, says Knight, and you have to be the grown-up. ‘I’ve heard younger teachers say, “I didn’t want to be mean,” but children know that they’re safe when they know where the line is.’

Positivity is essential when teaching young children, says Schrepfer. ‘They listen more to the tone of your voice than your actual words.’ As well as drawing on all her years of experience, Schrepfer says you also have to ‘tap into your inner child. For me, teaching little ones is far more about offering positive human connection through dance than focusing on technical details,’ she says. ‘It’s about planting the first seeds of care, attention, curiosity, and the discipline that ballet brings to small humans who are just beginning to explore the world.’ She clearly loves her work, adding, ‘it is a privilege to play a part in shaping another person’s early experience of dance and of themselves.’

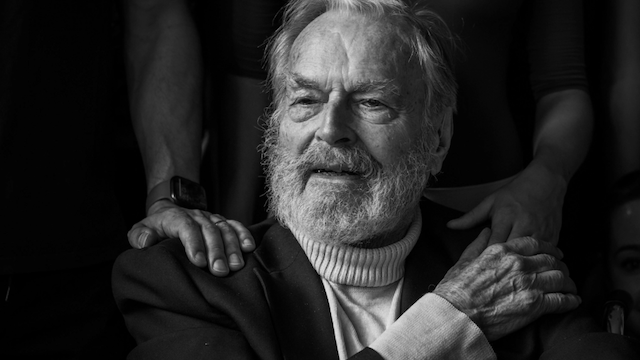

‘You have to tap into your inner child. It’s about offering positive human connection through dance’

Lydie Schrepfer

Lyndsey Winship is the Guardian dance critic and author of Being A Dancer.

Mandy Mackenzie Ng is a visual designer based in London. mandymackenzieng.com