FEATURES

Labours of love

Behind every professional dancer is a shadow support system committing time, energy and hard cash to help a child succeed. Sally Howard explores the highs and lows of being a ballet parent.

Read more

Settling the score

Ballets can live in memory and on film – but nothing captures their details and essence like a Benesh score. Sarah Crompton discovers the precise magic of notation.

Read more

In living colour

Audacious and imaginative, Léon Bakst’s Ballets Russes designs created a sensation. A century after his death, Jonathan Gray explores Bakst’s influence on ballet, fashion and design.

Read more

Walk the line

Eyes up, swaying hips, no smile. Fashion models have used the same fundamental walk to showcase clothes for over a century. But how easy is it? Veronica Horwell joins a catwalk workshop.

Read more

In other words

The words we use and hear in dance classes can have a lasting impact – for good and bad. Lyndsey Winship explores how teachers can harness the power of language.

Read more

Testing times

100 years on from the first RAD children’s exam, Rosemary Waugh looks at how exams have changed, and how their fundamental principles hold true.

Read more

Dance Gazette Top 40

Music and dance are intimately linked. Sanjoy Roy explores this essential relationship, and we share the Dance Gazette Top 40 – music for movement ranging through place, time and style.

Read more

Inside the music

Dancers are often praised for musicality – but what does that mean? Lyndsey Winship asks dancers, musicians and coaches at The Fonteyn.

Read more

Scene Change

Ballet classics can contain beloved dance and music – but also outdated cultural stereotypes. Can we reimagine them? Phil Chan offers a sound solution to problematic music.

Read more

The long goodbye

What happens when a student decides to move away from ballet? How do teachers feel when someone they have known since childhood leaves their class? Alice Robb explores how to say goodbye to ballet.

Read more

ACTION!

Who does the daredevil stunts for action movies – and why does a ballet background help? Veronica Horwell investigates.

Read more

Total immersion

Audiences flock to immersive theatre experiences, choosing their own path through action that happens all around them. But what are they like to perform? Writer and dancer Isaac Ouro-Gnao shares a view from the inside.

Read more

Paint job

From chalk and lard to gold leaf and mascara: Vera Rule reveals the hidden history of ballet make-up.

Read more

Sound of The Fonteyn

The Fonteyn – the RAD’s prestigious international ballet competition – took place in person for the first time since 2019. The final was held at His Majesty’s Theatre, the opulent London theatre that is home to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera – and Dance Gazette was there to capture the evening in sound.

Read more

Family guy

From the RAD’s Production Club to the world’s great ballet companies: Jonathan Gray explores the life and legacy of choreographer John Cranko, who died 50 years ago.

Read more

Bullet at the ballet

One critic described Mikhail Baryshnikov as ‘a shining golden bullet’ on the ballet stage. Jonathan Gray looks back on his miraculous classical career.

Read more

Misha and me

Even as his ballet career drew to a close, Mikhail Baryshnikov embraced modern dance, screen acting and experimental theatre. Artists including Mark Morris, Robert Wilson and Willem Dafoe tell Sarah Crompton about working with Baryshnikov.

Read more

Golden thread

From students to teachers, from adults taking up ballet in later life or using their dance training to pivot into a new career – the RAD forms a supportive thread through many dancing lives. We follow varied RAD stories from Brazil, Greece, Australia and the UK.

Read more

Queen Elizabeth II

Queen Elizabeth II, the UK’s longest-serving monarch, died on 8 September aged 96, after reigning for 70 years. She had been Patron of the RAD since 1953.

Read more

Happiness. Inc

What makes a happy organisation? As the RAD asks its members how they feel about the Academy, Ella Satin explores what makes for a happy company or workplace.

Read more

Home and away

Teaching is a portable skill, one that can carry you across the world. Jane Albert meets RAD teachers who have made new lives in completely new countries.

Read more

Safe spaces

Isaac Ouro-Gnao meets ballerinas and young dancers from Ukraine who have fled the Russian invasion and building new lives.

Read more

Permission to dance

K-pop’s high-concept dances have conquered the world from their native Korea. In Seoul’s dance studios, David D Lee meets both tourists and students determined to break into the industry.

Read more

Welcome to Battersea

Take Veronica Horwell’s unique audio tour through Battersea’s rich history – a place of pets, parks and power, and home to the RAD.

Read more

Here, queer and dancing

From folk dance and New York ballrooms to Strictly Come Dancing: Emily Garside explores the history and power of queer dance.

Read more

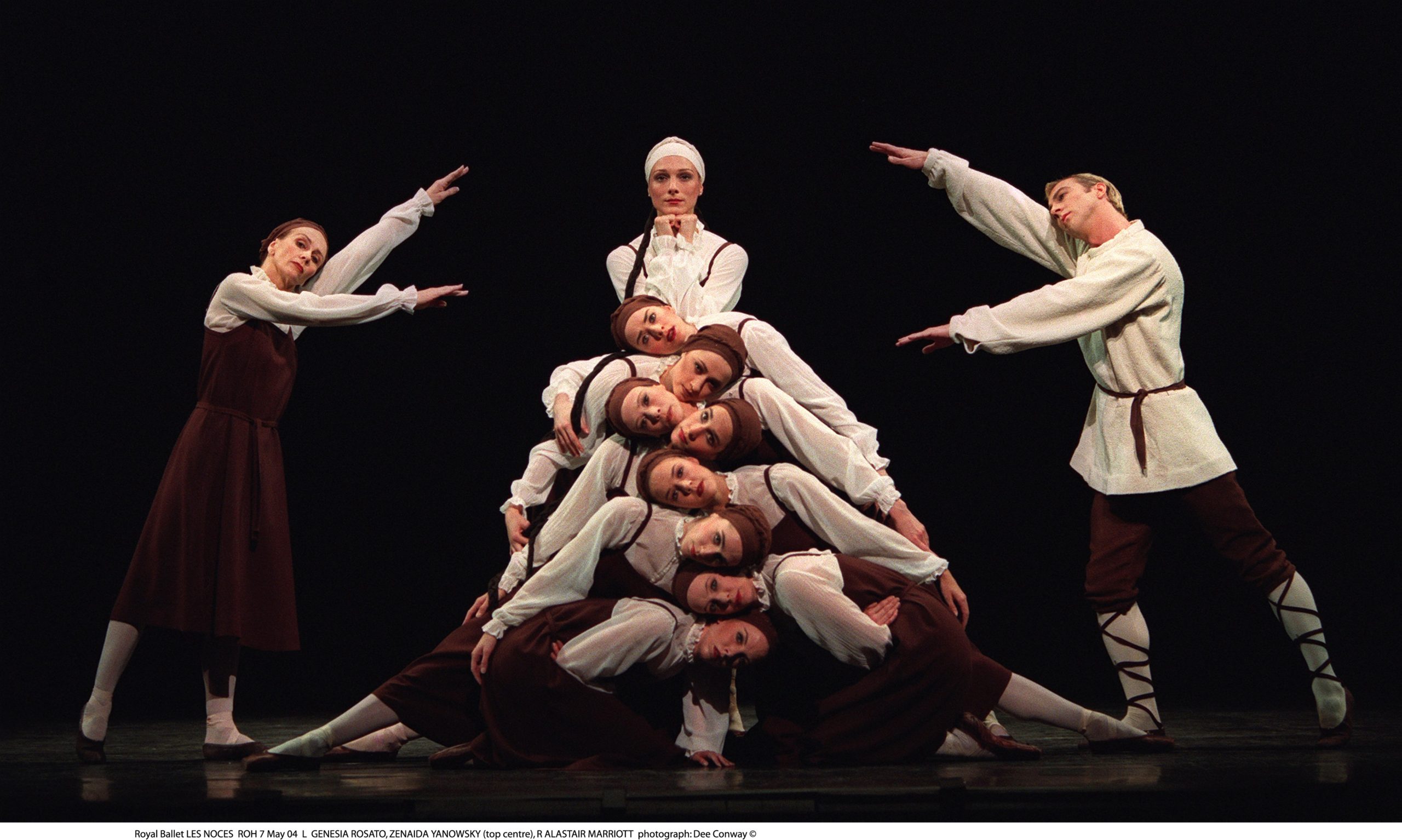

Long way from home

As Bronislava Nijinska’s masterwork, Les Noces, approaches its centenary, Lynn Garafola traces its evolution and shattering effect.

Read more

Say it with silence

A colourful new film based on the classic ballet Coppélia puts live action alongside animation. The cast of star dancers had to discover how to communicate on camera.

Read more

Moving pictures

When dance meets film, magic can happen. Isaac Ouro-Gnao speaks to the makers of three striking new movies: documentary, fashion film and major Hollywood musical.

Read more

Picture this

As the RAD launches a portrait competition for its new London headquarters, Sarah Crompton asks leading portrait artists how they capture a personality in paint.

Read more

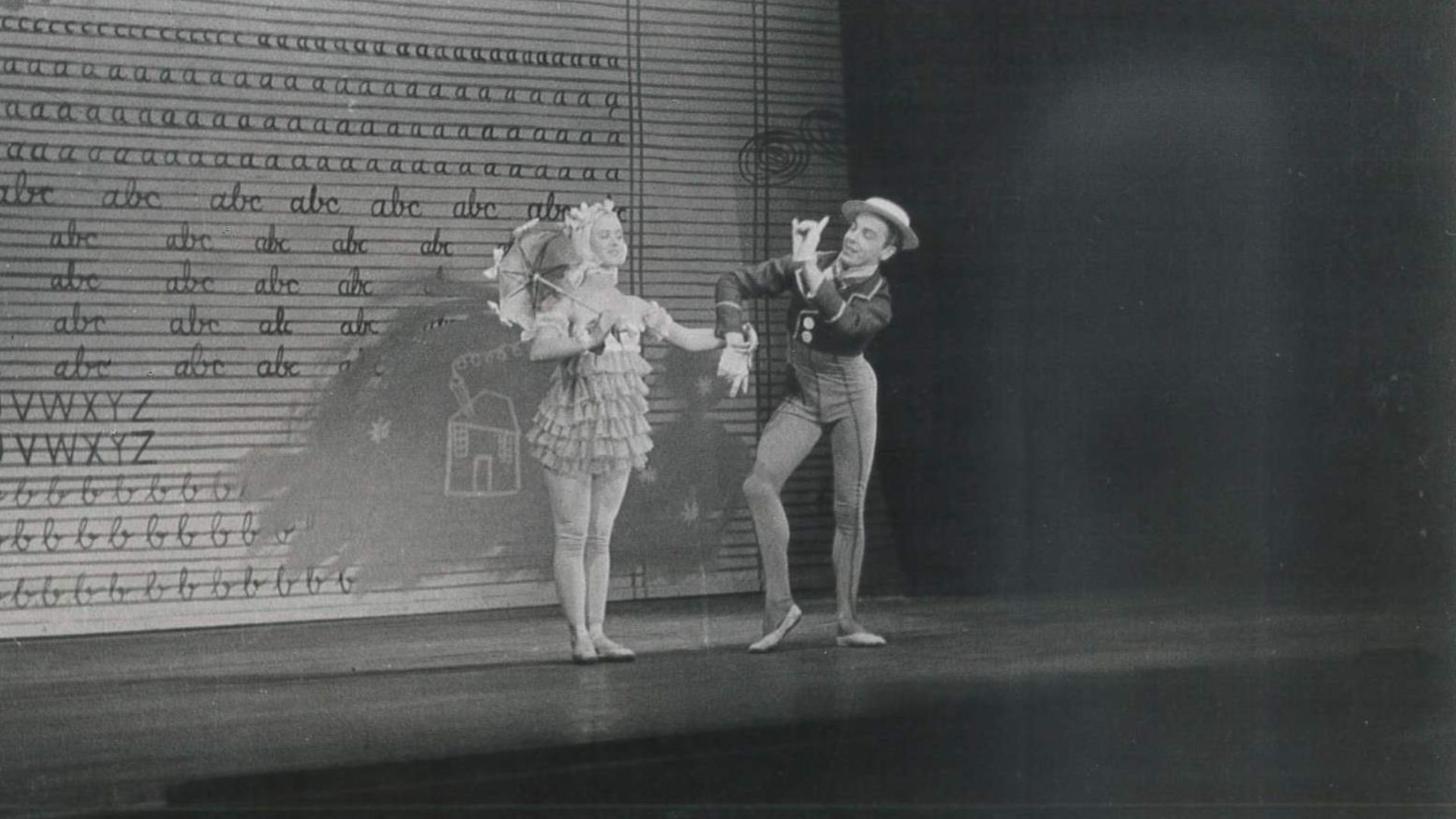

Living doll

The RAD’s new portrait competition celebrates its first President, Adeline Genée. But who was she – and how did she rise from the music hall to the peak of British ballet? Carol Martin reveals the woman behind the porcelain princess.

Read more

Founding father

The French painter Poussin is often called the father of classicism. He was also fascinated by dance – so Rosemary Waugh asks a choreographer and a curator to delve into his paintings.

Read more

Breaking the mould

As breakdancing hits the Olympics, we meet b-boys and girls in South Korea.

Read more