At the end of last year we launched a new set of values for the RAD, created through workshops with colleagues and members.

We are:

Creative Innovators

Champions of Wellbeing

Exceptional Together

Open to All

Happy To Help

There’s so much in each of them but today I’d like to talk about ‘Happy To Help.’ As we embark on this journey together, I want to share not only what this value means for our organisation but also how it resonates with me personally.

At the core of ‘Happy To Help’ lies a simple yet profound ethos: the joy of service. It’s about cultivating a culture where every interaction, task and moment is infused with a genuine eagerness to support and uplift one another. This is not just about fulfilling obligations, but embracing the opportunity to make a positive difference in the lives of others.

For me, this means leading by example. Whether lending an ear to a colleague or rolling up my sleeves to tackle a challenge alongside my team, I strive to embody the spirit of service in everything I do. A quote from Laura Ashley has always resonated with me: ‘we don’t want to push our ideas on to customers, we simply want to make what they want.’ I believe this ethos should permeate every aspect of the RAD from our colleagues to our members.

From our teams assisting students at HQ to our teachers all over the world going above and beyond to ensure every student feels supported, this value serves as our guiding light. Putting members first is paramount because you are the lifeblood of the RAD. By prioritising your needs, we build on the long-term relationships that have made us who we are for over 100 years. A boss once told me, ‘do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do.’ I totally believe this. It’s vital that we make sure members feel valued and heard – not just because that’s how to build a successful business but because it’s the right thing to do. This approach drives innovation, striving to anticipate and exceed expectations. Ultimately, prioritising customers is not about increasing revenue; it creates meaningful connections and delivers genuine value, the foundations of any great organisation.

‘A boss once told me: do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do’

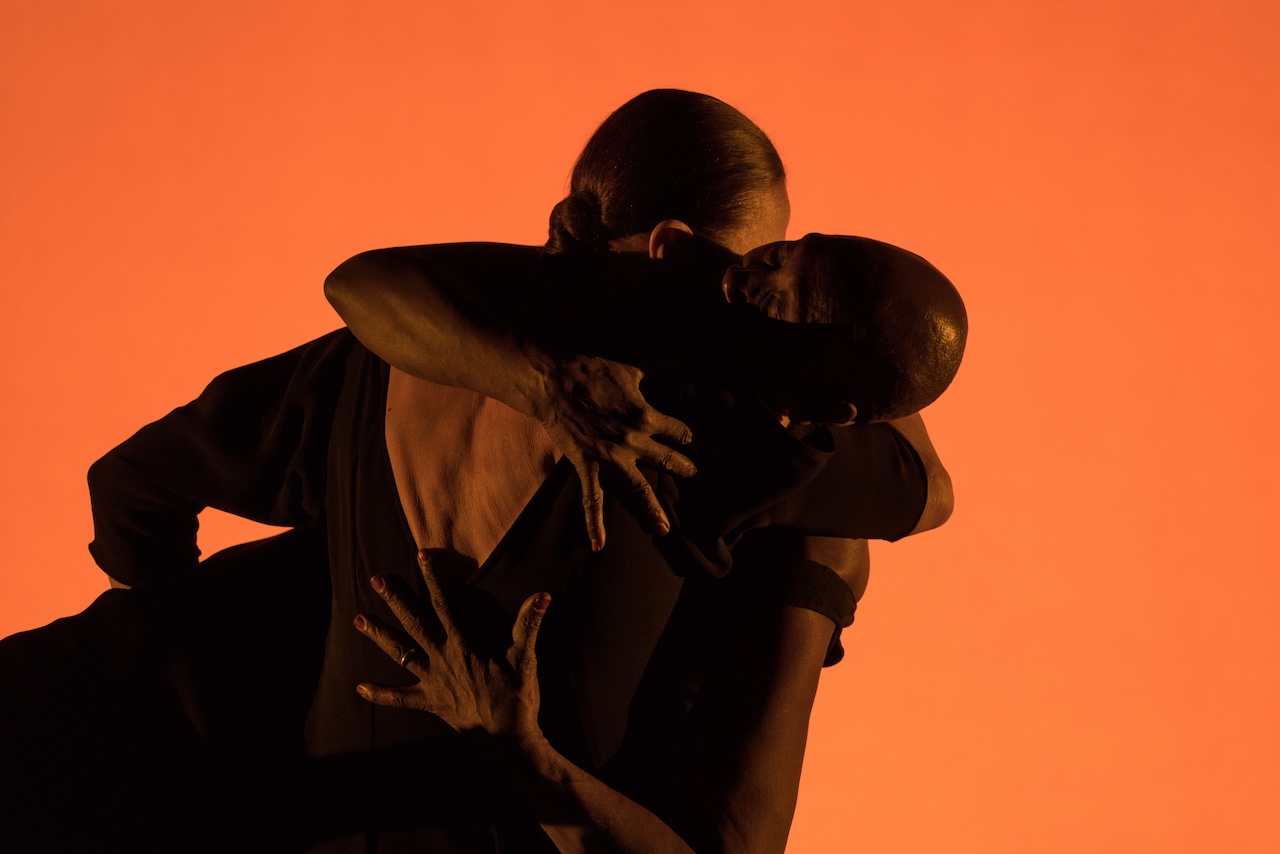

Being ‘Happy To Help’ is not just about responding to needs; it’s about proactively seeking ways to make a difference. We’re constantly looking at ways to help members in this fast-changing world. Dance and dance teachers wield a transformative power that extends far beyond the studio walls. The art of movement nurtures individuals to become the best versions of themselves. Dance instils invaluable life skills: teamwork, perseverance and confidence. Dance teachers are both mentors and role models, guiding students towards self-discovery and personal growth. Your dedication and passion not only shape skilled dancers but also compassionate, empathetic individuals who contribute positively to society. In a world often marred by division, the transformative impact of dance shines brightly. It’s our job at the RAD to help you in that.

We haven’t always met the mark in providing exemplary customer care, and there’s still a considerable distance to travel. We’re dedicated to learning from our missteps, refining our processes and enhancing our commitment to serving you better. Your feedback fuels our determination to evolve and exceed your expectations. Your trust in us is invaluable, and we’re grateful for the opportunity to earn it anew each day.

With ‘Happy To Help’ as our guiding light, let’s choreograph a future filled with unity, support and boundless possibilities.