INTERVIEWS

Opportunity knocks

Goodbye spotlight, hello Power Point: Alexander Campbell, the Royal Ballet Principal, is the RAD’s new Artistic Director. He tells David Jays that he’s excited for the role ahead.

Read more

A sheep burst into the room

The RAD has been sending examiners around the world for decades – initially in a world before mobile phones, internet or email. The RAD’s remarkable retired examiners share some unexpected travellers’ tales.

Read more

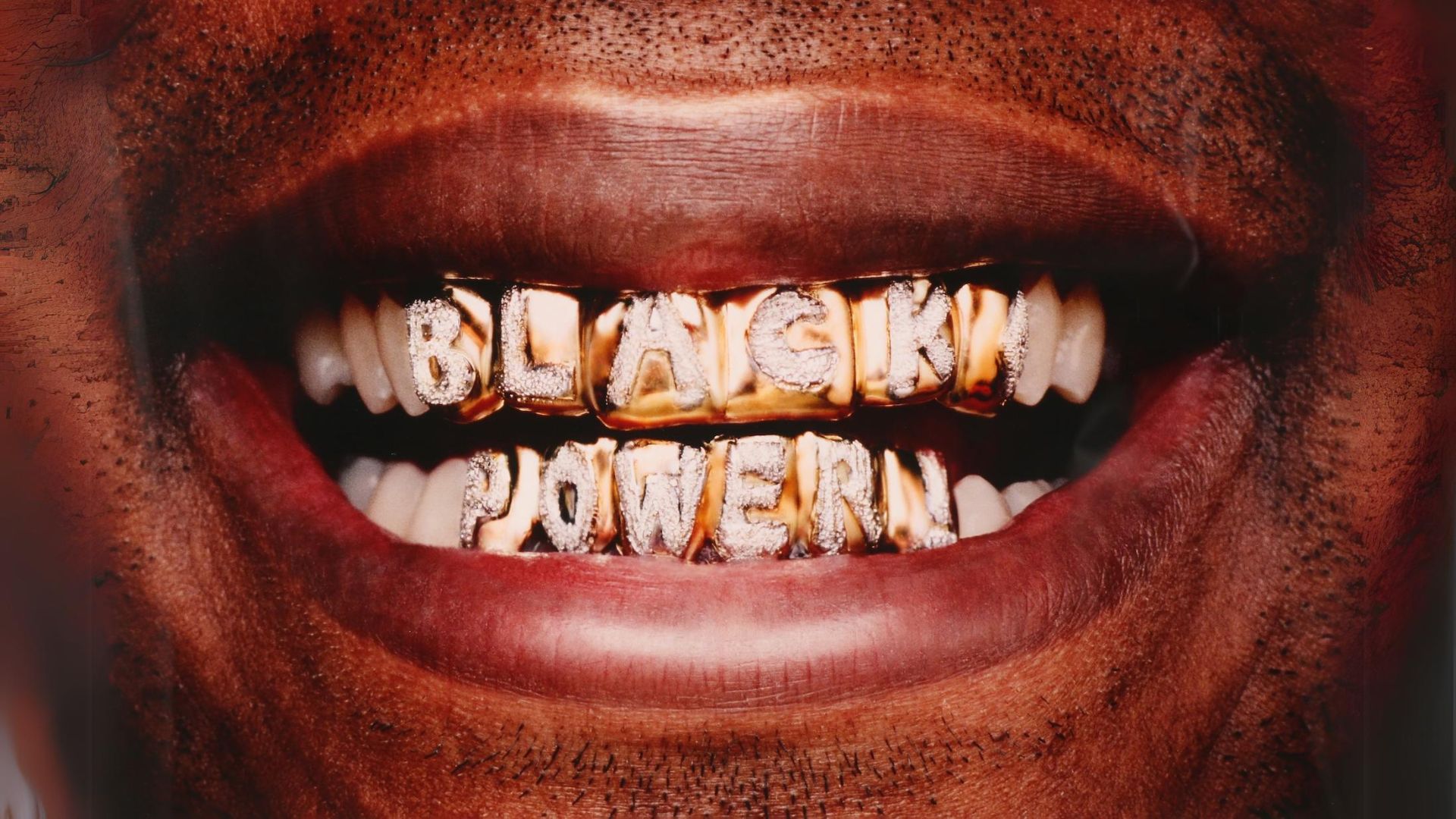

Fight the power

Celebrating 50 years of hip hop, expert voices – including the rapper Ice T – talk dance, relevance and sneakers.

Read more

Music matters

Dancers and singers live and breathe music. In this special audio feature, we visit the Royal Opera House in London to ask a leading soprano and principal ballerina about working with music, and how it feels to perform to a mighty score.

Read more

Together forever

This issue of Dance Gazette brings together three pairs of dance people to share and compare experiences. Dancers in different styles, RAD teachers of different generations, RAD directors in different countries – do they share more than divides them? Deirdre Kelly listens in.

Read more

Full circle

From gold medallist at the Genée to choreographer at the Fonteyn – the Royal Ballet’s Valentino Zucchetti tells David Jays about creating work.

Read more

‘It’s a force stronger than me’

David Hallberg – star dancer, now artistic director of the Australian Ballet – tells David Jays about surviving bullying, being the boss and why dance still compels him.

Read more

Meet Mr Baryshnikov

Q&A interview with Baryshnikov and a report from the award ceremony at Buckingham Palace.

Read more

Ambassadors assemble

The RAD has been part of dancing life for both Céline Gittens and Steven McRae, from early steps to becoming principal dancers. Now, as the RAD’s new ambassadors, they share experiences.

Read more

Meet the boss

Tim Arthur has worked in theatre, publishing and finance – now he’s the RAD’s Chief Executive. Learn about his love of the arts – and unexpected dancing past.

Read more

Leading the way

Carlos Acosta’s life would have been very different without ballet. He is committed to sharing the artform – as artistic director of Birmingham Royal Ballet and through a new partnership with the RAD.

Read more

Luke Rittner: exit interview

Dance Gazette invites RAD National Directors to put questions to Luke Rittner as he prepares to stand down as Chief Executive.

Read more

Forever Amber

Australia’s star ballerina on coaching for The Fonteyn and passing it forward.

Read more