Congratulations on becoming the RAD’s new Chief Executive!

Thank you – I’m still pinching myself!

Why did the role of CEO appeal to you?

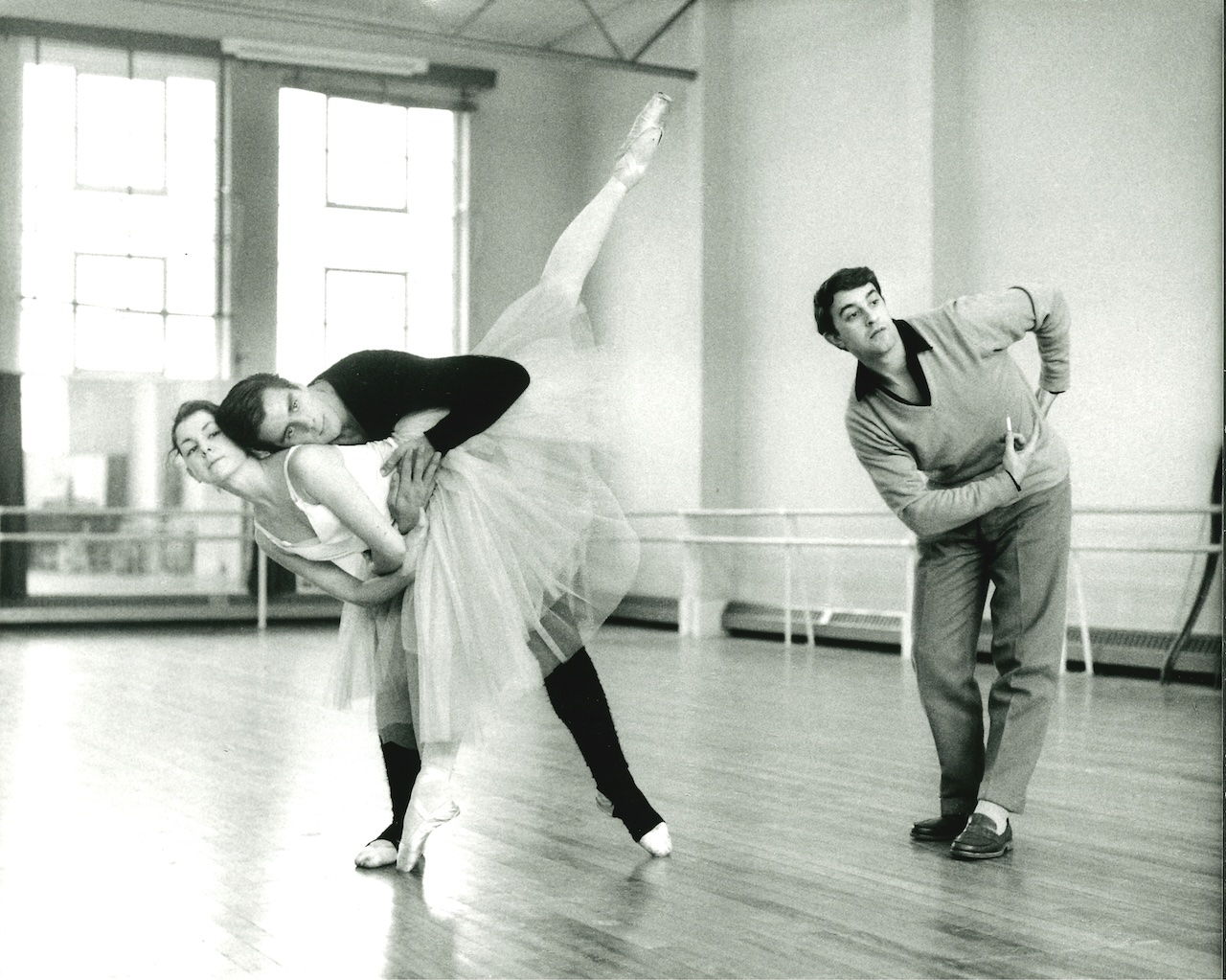

First of all is my love of dance. I have a bit of heritage here – a relative, Mary Honer, was a leading dancer with the Vic-Wells Ballet in the 1930s before going into musical theatre. I used to pore over pictures of her. I then did ballet and my RAD exams as a child, and have continued to dance throughout my life. I was never going to be a professional dancer or teacher, but it’s been very important to me. Now I take classes at the RAD: adult ballet and Silver Swans. And I’m an RAD member!

Because of that love of dance, I did a cold pitch to the RAD, asking: can I be of use? For the last year, I’ve been on the Finance and Risk Committee. When, to everyone’s surprise, Tim Arthur [the previous CEO] left, I thought: Now is my time.

And how does your work background fit the RAD?

I started my career in the arts – at Sadler’s Wells, the Academy of St Martin in the Fields and an artists’ agency. I then trained as a teacher, but although I enjoyed it, it wasn’t quite my thing. Then I went into the civil service: most recently, I was chief executive of an agency of the Treasury and then a non-executive director of a professional membership body. So the RAD role is an amazing blend of everything I’ve done.

It is a very varied career – is there a connecting thread through it?

I’m not someone who had a life plan. I have always loved the arts, and have learned that it’s important that one’s personal values and the values of your work are very aligned. For me, public service spoke to my personal values. The RAD is also about what is good for individuals and society. So I can see that thread running through my career. In the end, it’s about taking opportunities when they come your way.

Many of your leadership roles have involved ensuring value for money and achieving financial targets. Are you comfortable with those fierce conversations?

Yes, I’ve had quite a few difficult conversations. I ran an efficiency programme at the House of Commons, and in my most recent role reviewed how effective government organisations were. But my belief is that everybody, in the end, is trying to do a good job. I find people fascinating, so it’s about trying to understand their perspective, so that you can have a meeting of minds. For the RAD, I feel that if we do right by our members and do right artistically, then the money will follow.

Are you still enjoying dance classes?

I have just loved my three classes a week, and hope I can continue them. I had a double hip replacement three years ago, and dance has been an amazing part of my rehabilitation. I’ve also made a wonderful social network through it. It’s fabulous.

Is it important to you that you’re the first female Chief Executive of the RAD?

Some people have commented that it’s great to have a female CEO. I’m really glad that that is important to members, but I want to be a good CEO first and foremost. I’m very happy to talk to members about my experiences. It’s not always been plain sailing, so I’m always keen if there’s anything I can do to support other women. If it inspires other people, that’s great, but it’s not what I’m going to be leading on.

The RAD has been through several years of change – is there more to come?

We have only just got an exciting new strategy, but there are still priorities to be decided within that. I want to take time to engage with the directors, the board and our members, so that we get those priorities right. Come back to me in a year’s time, and we can have another conversation!

The RAD is such a varied organisation – where do you begin?

The RAD is a whole multitude of things – a lot of people only see a segment of it. I’m interested in understanding how we can do well by our members, and create a sense of community. The challenge for any organisation with a history as long as ours is: how do you esteem the history and traditions, while also changing for the future? We have our exams, which always need to keep refreshed. We educate teachers – what does that look like for the future? And I’m also interested in the Benesh Institute, and the application of modern technologies to choreography and notation. There’s so much to explore – I’ll be like a child in a sweet shop!

What are you most looking forward to about the role?

I’m really looking forward to getting out and listening. That is my job in the first few months. Listen, listen, listen. The RAD is a global organisation with a global membership – I want to understand all the different perspectives. So I’ll be listening hard.