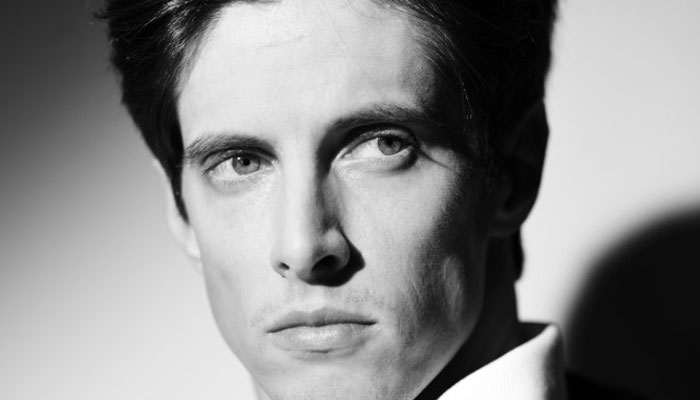

‘I was just born to be a fan of things.’ Brandon Taylor is smiling down the Zoom. The American writer is a fan of, among other things, medieval European history; 19th-century Russian portraiture; 20th-century literary theory – and, it turns out, ballet.

None of these are necessarily passions you might expect to animate a 32-year-old novelist from Iowa, but Taylor – whose debut Real Life was shortlisted for the Booker Prize last year – is your man for recondite enthusiasms. ‘I tried being the very cool, very aloof artist,’ he says. ‘I tried looking down my nose, but I don’t enjoy it. I’m such a nerd about things that I enjoy – I have no cool.’

I would happily quiz Taylor about his strong views on the Tudors (‘usurper trash’) but ballet calls. What ignited that particular enthusiasm? He dates it precisely – to World Ballet Day 2016. WBD is when international classical companies and institutions including the RAD open a window not on performance but on their daily grind – the routine of class and rehearsal. ‘I’d always had an interest in dance, but it never occurred to me that it could be something you could write or do a story about,’ Taylor says. He was working long days as a graduate student in biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin, and ‘one of the things I was doing to keep sane in the middle of the night was I’d browse YouTube, and I came across the video of World Ballet Day in late fall 2016. And I was like, wait, there’s a video of the entire morning class? It was the best thing I’d ever seen.’

‘I was like, wait, there’s a video of morning class? It was the best thing I’d ever seen’

WATCH An extract from Wayne McGregor’s Chroma at the Royal Ballet

He enjoys staged ballet, but admits that his devoted nerding is drawn to ‘nitty-gritty process-oriented stuff. I felt incredibly privileged to get a behind-the-scenes sneak peek into how these dancers start their day. Everyone’s got a slightly different ritual: some people take the legwarmers off when they move to centre, some people leave them on, some shed layers as they get warmer. When people think of dance it’s like going to the museum, this distant, cold art form – but you get this glimpse into the human behind the artistry and I loved it so much. And I was like: oh, now I know how to write about this.’

That realisation bears fruit in Filthy Animals, his first short story collection. Six of the stories track a fraught triangle between three young people at a midwestern university, as Lionel, struggling with his emotional health and career prospects, becomes emotionally tangled with Sophie and her boyfriend Charles, both dance students.

Bodies, their fragility and needs, are at the heart of these stories. ‘Flesh’ tracks morning class when Charles stumbles in, hungover after late-night sex. He feels rough, his injured knee twinges – but all dancers know you don’t skip class, no matter what. ‘It is mind-blowing to me,’ Taylor admits. ‘I used to work in a lab, and you could tell after the summer vacation who hadn’t been in lab all summer. Their pipetting wasn’t as crisp, their experiments didn’t run as smoothly. For dance, where your craft literally lives in your body, I do think you have to be in it continuously, otherwise you lose your touch and feel.’

‘I know what it’s like to be young and have a passion and want to be an artist,’ he muses. ‘Now I had access to a visual vocabulary, a way into this form that I’d loved for so long but didn’t know how to write about.’ Watching dancers all over the world go through their morning motions was key. ‘You can see they’re working on things. You see the bones but also the spontaneous play of it.’ Whether they’re in lab, in bed or in class, Taylor homes in on the tensions that bodies carry. In the studio, dancers size each other up (Sophie is the acknowledged star of her cohort, while Charles is second-tier, as long as his knee holds out) and are unillusioned about their bodies. ‘It is an unsentimental attitude towards oneself, like, “I’ve just got to get this hunk of meat into the air for 2.5 seconds and down again”. So much of dance is paying attention to your body until it’s less a body and more a machine that does things.’

In a pre-interview email exchange, Taylor named Justin Peck, Wayne McGregor and Charlotte Edmonds among favourite choreographers: ‘neoclassical and modern-adjacent stuff.’ Perhaps unexpectedly for a storyteller, these aren’t primarily narrative artists. ‘I’m as non-abstract as a contemporary writer can be,’ he agrees. ‘But one of the things I love most is when a piece bears some mark of its composition.’ In these dance makers, ‘you can see the sketch line, like artists who work in charcoal. I love the human mark of it.’

WATCH A trailer for Justin Peck’s Heatscape at Miami City Ballet

‘I love social conflict –

not in my real life, but in my art’

Taylor writes cool but reads scalding hot. Does he respond physically to the emotions that scorch through his work? ‘When I was younger I would feel emotion very keenly,’ he admits. ‘I had no means of separation, I was in it. Now there is more of a separation, but I know I’ve hit on something really good when I feel a spike of anxiety – when it cuts through the distance I’ve managed to make for myself. The Lionel stories look into some dark, complicated places, and there were moments in the revision of Filthy Animals when I had to get up from my table and walk it off. But when I do feel a flush of anxiety when I’m writing, I try to pay attention. It’s about maintaining the emotional torque but not losing the artistry.’

World Ballet Day and the obsession it unleashed ultimately shaped Filthy Animals. Taylor wanted to follow characters through several stories (‘I have a hard time letting go’), and standalone tales alternate with Lionel’s encounters with the dancers. Their coffee chats and hook-ups feel unbearably high-stakes, especially whenever food is involved. A campus potluck, an unnerving shared pasta, the calamitous student supper in Real Life: Taylor’s dinner scenes are goosebumpingly tense. ‘I’m drawn to meal scenes because they’re one of life’s great locked rooms,’ he explains. ‘You go to someone’s house and eat their food – you can’t just get up from the table and go. All of us have been at the dinner table where someone says the thing they were not supposed to say. That’s where the real juice comes from. I love social tension, I love social conflict – not in my real life, but in my art.’

The publication of Filthy Animals will hopefully be less fraught for Taylor than his novel’s entry into the world last year. ‘It was a weird and brutal year,’ he reflects. Lockdown in early 2020 coincided with a period of illness. ‘I started having these horrible anxiety attacks and developed this panic disorder. I went to the ER 10 times over a three-month period.’ Prioritising health over self-promotion, he assumed Real Life would disappear without trace, only for it to hit the Booker shortlist. The story of a Black, gay scientist’s response to aggressions, micro- and otherwise, in grad school was often taken as autobiographical, yet Filthy Animals, ‘in many ways is a much more personal book. It was born out of the darkest period of my life.’ And he chuckles.

Filthy Animals is far more than dance lit, yet it gets to the heart of something about a life in dance – its immediacy and precarity. At one point, Charles realises he’s being honest, ‘because something in him hurt, and for a dancer pain is always the way you know something is true.’ How does Taylor intuit this so acutely? ‘It comes from that enthusiasm,’ he explains. ‘Once I get into a thing I get into it. It comes from a lot of watching dance, documentaries, interviews with dancers. And then thinking about the analogues in my own life – working in lab, pursuing with fanatical dedication a singular pursuit, and what it costs you.’ We’re back to the rewards of curiosity and enthusiasm. ‘I’m a super fan of things,’ he says happily. ‘When I engage with something I engage with it fully. I commit.’