What happens when four high-flying contemporary choreographers dip their toes in the hallowed waters of Swan Lake? Eric Gauthier is determined to find out. Pre-pandemic, the artistic director of Gauthier Dance (resident company at Stuttgart’s Theaterhaus) invited Marie Chouinard, Cayetano Soto, Hofesh Shechter and Marco Goecke to put their own 20-minute spin on the swan theme, giving them carte blanche to create a work in response to ballet’s most famous tragedy.

Then Covid came along and the Swan Lakes project, initially scheduled for summer 2020, was put on ice for a year. Now – corona-permitting – the brand-new bevy of Schwanensees should land on the Stuttgart stage this July. In the meantime, Gauthier has been further reshaping the shores of Swan Lake for his dancers, commissioning 16 new solos (complete with bespoke music) for The Dying Swans Project, each one captured on film.

Why all these cygnine shenanigans? It might seem like a risky choice given the abundance of versions out there, from stage to screen, spanning parody and pastiche through to Alexei Ratmansky’s reverent reconstruction of Petipa and Ivanov’s 1895 St Petersburg production, while the fairy tale got a feral rewrite in 2016 with Michael Keegan-Dolan’s Loch na hEala, set in contemporary Ireland. And of course, Matthew Bourne’s male swans cast long feather-legged shadows.

‘I’m from the ballet world,’ explains the Montreal-born Gauthier, who trained in Canada and danced with the Stuttgart Ballet for 12 years. ‘I lived through Swan Lake many times. Sometimes it got a bit boring but it’s a big legacy and a great piece of dance. As I’m running a modern dance company I thought I’d give it a twist, do Swan Lake but not like everybody else and not with a story from A to Z. I thought what if I put an “s” at the end of Swan Lake? How would that look? Are there two different lakes, three or four?’ He decided on a quartet, ‘a good round number. A lot of companies do mixed programmes with two or three parts. I thought it would mix it up even more if it had four parts.’

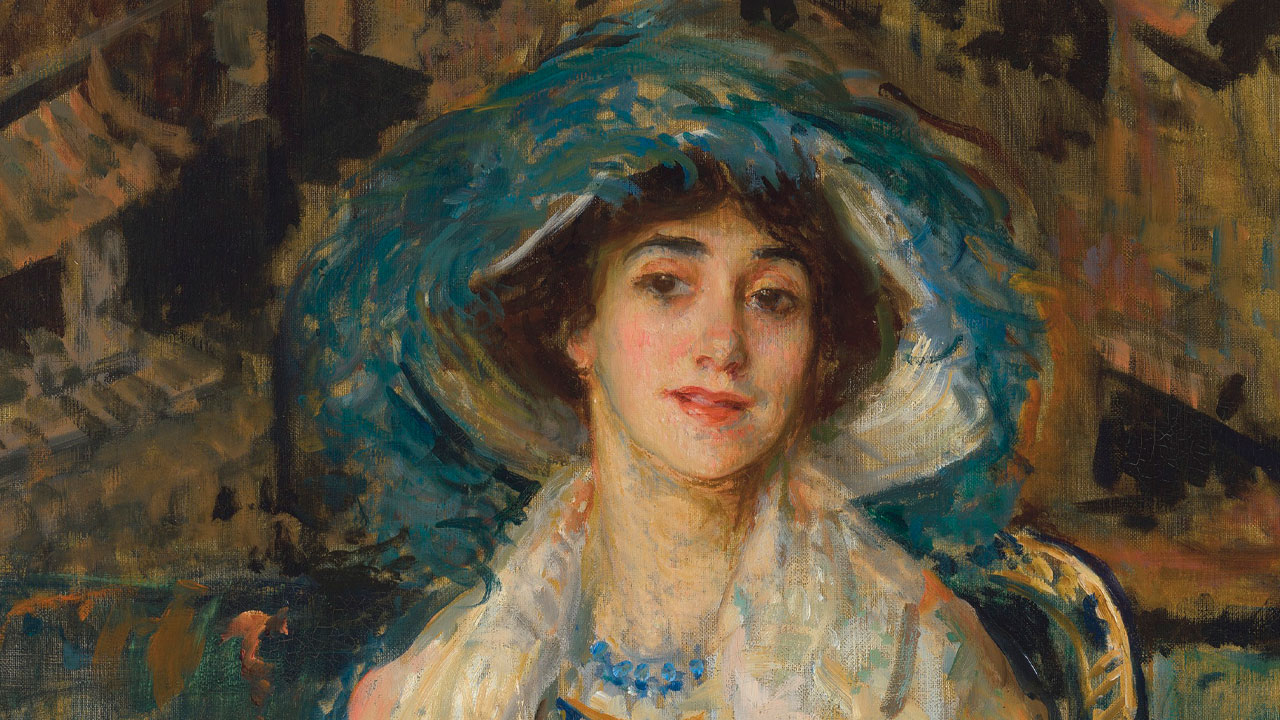

‘I don’t even know what Swan Lake

Marie Chouinard

looks like. It’s not a ballet I watch’

With the idea hatched, Gauthier had to pick choreographers. Now that his 13-year-old company ‘has a good name and standing’ he has the luxury of being choosy, he says, seeking out dance makers who would approach the subject ‘in a very special way.’ First on the list was Marie Chouinard, a fellow French-Canadian whom he describes as ‘our queen bee, our Pina Bausch.’ Chouinard, it turned out, wasn’t exactly a fan of the source material. ‘She said, “you want me to do something with Swan Lake? I don’t even know what Swan Lake looks like, it’s not a ballet that I go and watch.” And I said, “I know, that’s why it’s interesting, you can research it!”’

Chouinard agreed to take part, on the condition that she could make a work for the company’s female dancers. ‘In Swan Lake, I’m not interested in the man who kills the woman!’ she says. ‘I connected of course with the music but not with the traditional images associated with it.’ She won’t be drawn further on her choreographic ideas and methods, other than to say, ‘it was a beautiful and intense process. I start a creation from intuition. Like a painter. You start working on your canvas and on it goes. This happens in the studio.’

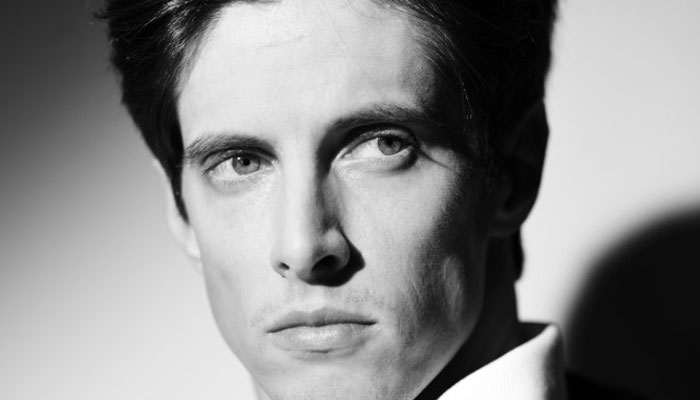

Like Chouinard, Hofesh Shechter – the subversive and groove-heavy golden goose of Britain’s contemporary dance scene – isn’t an aficionado of the original ballet. ‘Amongst my many sins, I’ve never seen Swan Lake live – my dance education was very flawed!’ he smiles over Zoom, in between bandwidth blips, from his London home. ‘I generally feel less attracted to ballets that have a plot. My work hovers between the theatrical and the abstract, even though there can be a strong sense of atmosphere and where we are, there’s no real story.’ So it’s no surprise to hear that he’s taking a sideways glance at the canonical classic. ‘What interested me about this was connected to the perception of beauty. Obviously today there are a lot of questions about what culture is and who defines it. I want to make the piece in a way that is not really beautiful. Swan Lake has been done so many times and has a particular taste and look to it, so my feeling is that I want to try and mess that look up.’

Along with choreographing the work for a cast of 10 male and female dancers, Shechter is composing the music (‘I might steal – or borrow! – a couple of lines from the original and give them a bit of a twist’) for Swan Cake. It’s impossible not to ask about this title. ‘You’re saying it and it brings a smile to your face – that’s what I like, it’s a bit jolting. It comes with a sense of sarcasm and sense of criticism but with humour.’

‘Swan Lake has a particular taste and look. I want to mess that look up’

Hofesh Shechter

While Shechter cooks up a creation with irony, Barcelona-based choreographer Cayetano Soto is delving into the grey area between traditional binaries. ‘What is missing for me in Swan Lake – I’m a trained classical dancer and I’ve seen many versions throughout my life – is you don’t see her transformation into a swan, how she turns into an animal.’ Soto notes that while ‘there are old versions from eastern Europe’ that sometimes show Odette’s metamorphosis, he was drawn to this idea of liminality. ‘I was very intrigued by it. How long does it last? Is it minutes? Seconds?’

For him, the transformation concept is rooted in both reality (‘we all transform in our lives’) and fantasy (the ‘dream of becoming a better being’). His work also aims to interrogate the distinction between bird and human. ‘I wanted to look as well at the connections and the instincts that we share with animals.’ After all, he notes, ‘everything we need is in nature. I always go back to nature. I feel more comfortable surrounded by animals than surrounded by somebody else!’

As if on cue, my cat appears and sits on the dictaphone, while Soto explains his choreographic process, a melding of his pre-planned intentions with the dancers’ sensibilities. ‘Each dancer has a unique personality. How this person uses what you’ve given them, it’s a process of growing, of discovering a new path together.’ It’s this individual artistry that moves him about certain Swan Lakes. ‘Artists like Margot Fonteyn, Nureyev, Natalia Makarova… people who have something to say with the character and make you truly believe that you are travelling with them. That’s the most remarkable thing.’

An imaginative journey and a shared experience: it’s what Shechter hopes Stuttgart audiences take from the new Lakes when the Theaterhaus opens its doors once again. ‘In these times I can only imagine an audience sitting in a theatre watching a performance together. It’s a powerful experience that we miss so much, that gathering of ideas and emotions.’ Whether feathers are ruffled or fantasies take flight, these Swan Lakes are set to be something special.

WATCH Evomere from The Dying Swans Project at Theaterhaus Stuttgart

Anna Winter is a dance critic and arts journalist,

writing for the Guardian, Exeunt and the Stage.

Are any other classic ballets ripe for reinvention?

We’d love to hear your ideas