Dance on film cannot replace the energetic exchange that happens live, on stage or otherwise. The closing and reopening of theatres over the pandemic has shown us that. Yet the surge of dance to the digital space feels inevitable, offering something unique, exciting and even comforting to artists and viewers alike.

It can overcome the issues of accessibility and offer archival preservation. It allows the artist behind the camera to lead the eye, focusing on intricate and emotive elements of a choreography we might miss at a distance. And it can be a great political tool with a message that can cross borders when physically doing so is impossible. This seems to be the case for three new dance films in very different genres: documentary, fashion film and Hollywood musical.

Cyrano

Cyrano is Hollywood’s latest blockbuster musical, with many exciting names attached. It’s directed by Joe Wright, famous for period drama adaptations Pride & Prejudice (2005) and Anna Karenina (2012). It draws from Edmond Rostand’s 1897 play and Erica Schmidt’s 2018 stage musical. And it stars the incredible Peter Dinklage (Tyrion Lannister from Game of Thrones).

Set in 17th century France, poet and soldier Cyrano loves Roxanne (Haley Bennett) but she falls for Christian (Kelvin Harrison Jr). Tasked to physicalise the unspoken passions is yet another renowned name – Belgian-Moroccan choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui.

‘There’s a scene where Roxanne is getting a letter from Cyrano but she thinks it’s actually from Christian, and she almost wants to make love with the letter,’ he says. ‘I made this choreography where she’s almost holding the letter really close to her heart [and whole body] because she is so enthralled by the idea of this man.’

Cherkaoui draws from organic body language, treating that as a starting point. ‘You don’t start with the final idea, you build to it,’ he says. ‘Once I know that the basic pieces are appreciated by the director, I can then multiply elements.’

He treats his ensemble choreography like a ‘murmuration of birds,’ matching big unison moves with intertwining, intricate fluidity. ‘I will ask the dancers to do it in such a way that it feels seamless,’ he says. ‘I like that sense of organicity [where] this rotation brings you towards the actor who sings. It’s this domino effect that I’m really interested in.’

‘I love movies – they allow me to be much more subtle’

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

This approach in turn ‘has had some sort of boomerang effect’ – so visually brilliant that it leads or changes the intended direction of a scene. ‘The way the camera was placed was a lot about me making proposals,’ he says. ‘Right away, I would have options where I would say to the dancers, we’ve got to be close to each other because it’s a frame – or you should spread out so we create more perspective. In that sense, I love movies because some things are easier. It allows me to be much more subtle.’

Having worked with Wright on Anna Karenina, a relationship of equal ideas has developed. ‘It’s more about finding the things that resonate with the director,’ he says. ‘My whole aim is just to make Joe happy and it’s a wonderful feeling when I achieve that.’

Watch

The trailer for Cyrano

Bloom on Tiptoe

‘As a fashion film, showing the beauty of hanbok to the world is the most fundamental purpose of this film,’ says director JaeKwang Han.

Hanbok, a Korean traditional costume, contains diverse dress codes and symbolism that Han believes have ‘played an unrecognised role in naturally restricting women’s social activities.’

‘The unconscious social position of women throughout society and their corresponding patterns of behaviour still exist,’ he continues. ‘They exist as big walls for Korean women that they cannot overcome.’ Han, who studied for a master’s degree in fashion media at the University of the Arts London, is strongly motivated to shed such restrictions. ‘It’s time to bring out and express another identity that has been overlooked for such beauty.’

Bloom on Tiptoe is the result, winning the Best Dance award at the 2021 Canadian International Fashion Film Festival. The eight-minute film expertly blends dance, cinematic storytelling and Korean fashion to tell a feminist story of inner conflict and overcoming.

The choreography by Hyerim Jang is elegant and stunning, skilfully performed by Hyun Kim and Go-woon Lee. The two dancers, costumed in Tchai Kim’s striking white and black designs, are a joy to watch. Where gentleness and poise flow in one, sharpness and intricacy emanate in the other. And Han captures it with a choreography of his own in his direction and camera placement.

‘It’s time to bring out and express another identity’

JAEKWANG HAN

‘The contrast between the curved shape of the white costume and the straightened bold design of the black costume was manipulated to symbolise both the femininity and muscularity of each character,’ he says. ‘Through a transparent cloth, I intended to show the dancer’s body moving in a garment metaphorically.’

Han strongly values collaboration, citing fashion film Fallen (2015) by renowned choreographer Pina Bausch and filmmaker Kevin Frilet as an inspiration. He gathered his team after every single take to make collective decisions over elements such as the restrained lighting and its strong contrasting effects. ‘We monitored it together to discuss and revise the choreography to develop the movements in the frame,’ he says.

‘My film captures the beauty of the two dancers’ movements,’ he concludes. ‘The sculpting beauty of hanbok, the texture, colour, and line of hanbok. It is like showing the birth of a new hanbok, while at the same time means the discovery and rebirth of the trapped self.’

WATCH

Bloom on Tiptoe

Ailey

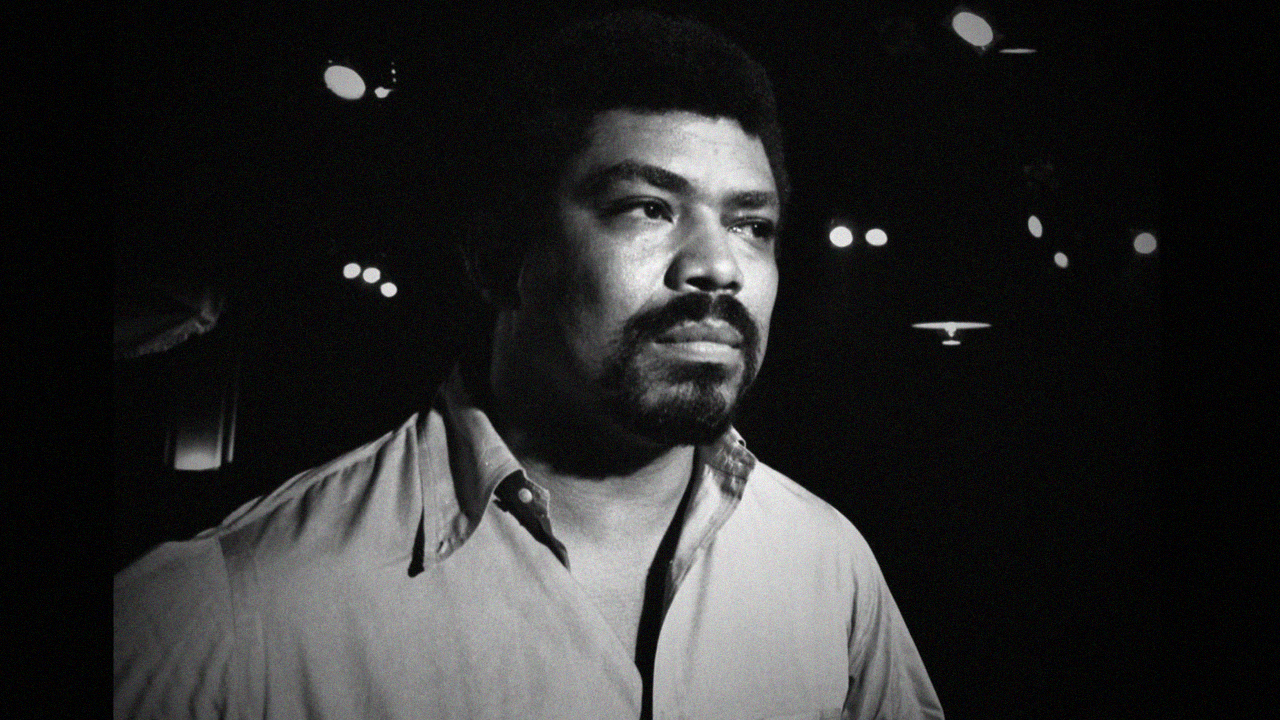

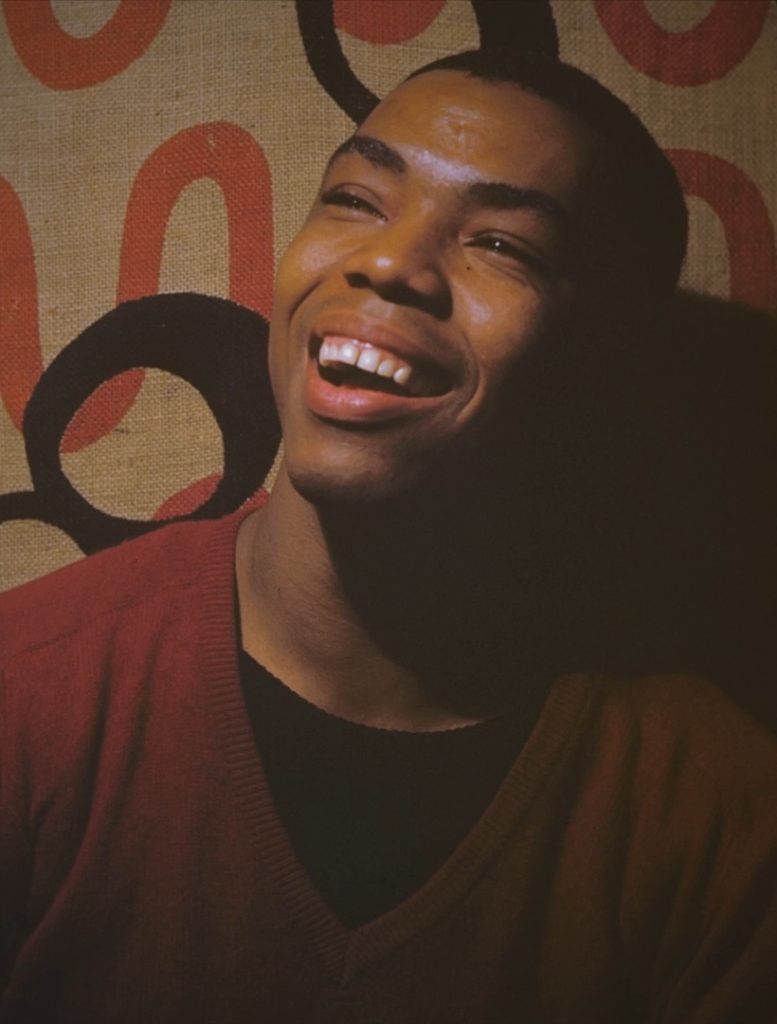

‘To tell Mr Ailey’s story only as a kind of birth and death is not true to his biography,’ says director Jamila Wignot. ‘So much of his story is that his spirit, his vision, his legacy lives on beyond his death in 1989.’

To capture this legacy, Wignot joins the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater as they rehearse Rennie Harris’ two-act Lazarus (2018), commemorating the company’s 60th anniversary. ‘Harris works in a totally different dance language of street dance,’ she says. ‘And yet here he was tasked with bringing a kind of experience that informed Ailey’s life to the stage. That just felt very serendipitous.’

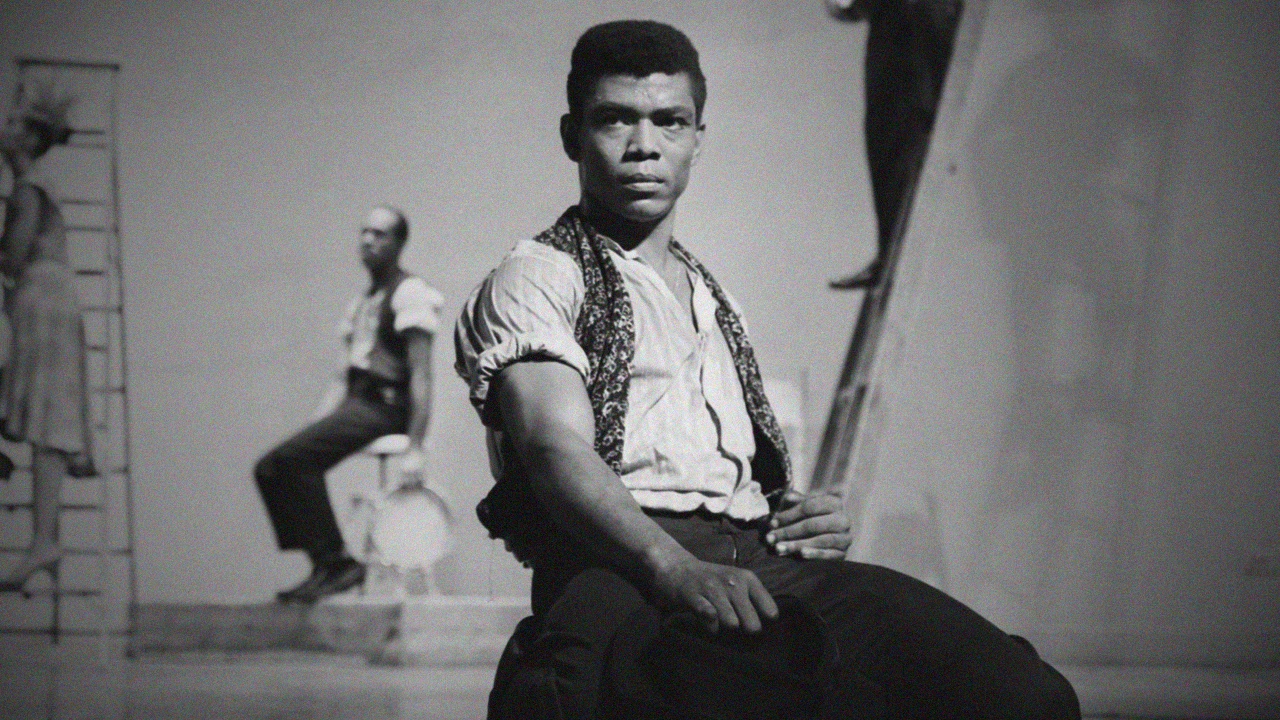

Many of Ailey’s ballets have been filmed and are quite accessible. Yet Wignot and archive footage researcher Rebecca Kent unearth archival footage, performances and interviews offering a much more intimate and personal picture of Ailey. There’s the breakout 1958 production Blues Suite, the 1971 performance of Cry (a loving tribute to Black mothers) and of course, the classic 1960 Revelations.

‘The dances really were informed by my personal preferences,’ she says. ‘I really wanted to include Masakela Langage because it is the only truly sort of political dance work that Ailey made in his lifetime. I wanted people to understand that side of him and that it was informed by it in part by the assassination of Fred Hampton [the Black activist killed by Chicago police in 1969].’

Another work, Memoria (1979), takes significant space, shedding light on a period of poor physical and mental health. ‘Once I understood the circumstances around the time that he created, it felt very much like a dance that we had to feature,’ she says. ‘It reveals so much about ways that he hadn’t taken care of himself.’

Ailey is known almost exclusively through his work. The added emotional weight and modern perspective on the motivations behind his creations feels like an honouring of that. ‘I always wanted the film to be a showcase about him as an artist,’ Wignot insists. ‘I don’t think there’s the deepest understanding of all that he was drawing upon. What does it mean? When a man can create such a warm embrace for everybody around him and yet doesn’t seem capable of allowing that adoration to truly come back to him? I want people to walk away with that question.’

Alvin Ailey. Photo: Yale/Van Vechten Trust

‘I wanted Ailey to be a showcase about him as an artist’

Jamila Wignot

Watch

The trailer for Ailey

RESOURCES

Isaac Ouro-Gnao is a Togolese-British multidisciplinary artist and freelance journalist.