Sometimes the biggest steps can be taken on the dance floor. When the tv chef John Whaite and his professional partner Johannes Radebe burst onto Strictly Come Dancing in 2021 they showed British television audiences the joy – and skill – of same-sex Latin and ballroom, to an overwhelmingly positive response. The first male same-sex couple on the hit show, they continued through to the final, ending as series runners-up. That audience positivity came from witnessing their brilliant skill as a partnership and Radebe’s inventive, assured choreography – but they also showed anyone who might want to dance with someone of the same gender that they could do just that.

For many of us, such contrasts of scale and same-sex dancing is no new phenomenon. The tango originated around the 1870s in Buenos Aires, often with males dancing together – in part due to an absence of women to practice with. But in the 1920s a rise in balls for LGBTQ+ people created spaces where gay men and women could socialise and indeed dance together. A precursor to the nightclubs that would also use dance as integral to socialising, they were spaces where men and men and women and women might engage in the popular dances of the day. During the ‘Roaring 20s’ and inter-war years, culture became more permissive, moving away from Victorian values. However, from the later 1930s and well into the post-war years, hate crimes against gay men increased and such dances went back underground. Same-sex dancing continued, but in a much more secretive society.

‘People come as they are, dressed as they like, and are accepted and welcomed’’

Francesca Canty

Same-sex ballroom has endured too, and in recent decades enjoyed a resurgence. In Britain, many outspoken advocates paved the way for the scene we see today. Jacky Logan created Jacky’s Jukebox on Saturday nights at Rivoli Ballroom in the 1990s, welcoming all sexualities. She continues to break gender norms by holding classes which help you to decide whether you fit the ‘leader’ or ‘follower’ ballroom dancing role, regardless of gender. Pete Meager launched Equality Dance – a ballroom and Latin dance school based in London – in 2017, which similarly aims to ‘teach people their role of choice’. This generated the UK Equality Open, a competition with categories for same sex and open couples; participants can join regardless of how they identify or whom they dance with. Things have evolved too with Equality Dance UK seeking to change the rules, and educate the broader ballroom community to allow same-sex ballroom couples and mark them fairly.

One spiritual home for the same-sex dance scene is London’s Bishopsgate Institute, an adult education organisation and cultural centre founded in 1894, and whose archives hold an extensive collection on LGBTQ+ history, politics and culture. Francesca Canty, Chief Executive and Artistic Director of Bishopsgate, is particularly passionate about this dance scene, having been part of it for some time – she calls it ‘equality dance’. ‘When I first went to Jacky’s,’ she recalls, ‘I knew nobody at all and now a lot of my closest friends, colleagues and collaborators are people I have met through equality dance. People come as they are, dressed as they like, and are accepted and welcomed – and I have to say I have not experienced that consistently at mainstream social dances.’

This welcoming space is important, particularly for LGBTQ+ dancers to feel they can be themselves. Growing this community has been important for Canty at Bishopsgate. As she says, ‘although I’m proud that Bishopsgate Institute is the home for equality dance in London, and I can see that the community likes to feel they are coming to a familiar and welcoming base, I’d like to see equality dance everywhere, including mainstream events welcoming equality dancers without a second thought.’

It’s a kind of lead-by-example approach (pardon the ballroom pun): if spaces like Bishopsgate can offer inclusive dance a home, maybe this area can grow. As Canty says, ‘our special collections and archives include LGBTQ+ history and culture as a rapidly-expanding collecting area, and we celebrate everyone’s story. It therefore seemed entirely logical to me that the equality dance community should feel at home at the Institute.’

Community spaces are vital for supporting dance. ‘The Latin and ballroom community isn’t the only community striving to be inclusive,’ says Canty, ‘or indeed the only space where LGBTQ+ dancers can feel at home. Folk dancing too has a strong, and lively tradition of allowing all partnerships. It’s partly a virtue of many dances not needing binary partners and the emphasis on community enjoyment over, say, competition or performance in other genres.’

Daisy Black, a folk dance caller based around Sheffield in northern England, describes the positive impact of non-binary dance. ‘If anything, using gender free terms has made ceilidh calling a lot easier! There’s no need to faff around trying to organise a newbie crowd onto the “correct” sides. We can get straight on with the dancing.’ She adds that, ‘learning to call gender free has really improved the accuracy of my descriptions too. I now describe dances in a more positional manner, which is helpful in dances like American contra, where people change sides and orientation.’

If inclusivity and quality can go hand in hand, there is also much to be said for the quiet queerness and inclusiveness of the folk dance community. ‘Certainly, the Morris and folk-dance crowds I move in are very queer,’ says Black. ‘My favourite festival, Inter-Varsity Folk Dance Festival, is a UK leader in developing new ways of being inclusive and accessible. They are thinking about how to make the festival an accessible space for those with neurodivergence, sensory issues and physical disabilities, as well as for gender.’

There’s something wonderful in the idea that inclusivity in one area fosters a wider inclusivity. That folk dance communities are truly opening dance to all is exciting and positive. Black also comments that as a hugely intergenerational dance scene, all levels are always welcome at events.

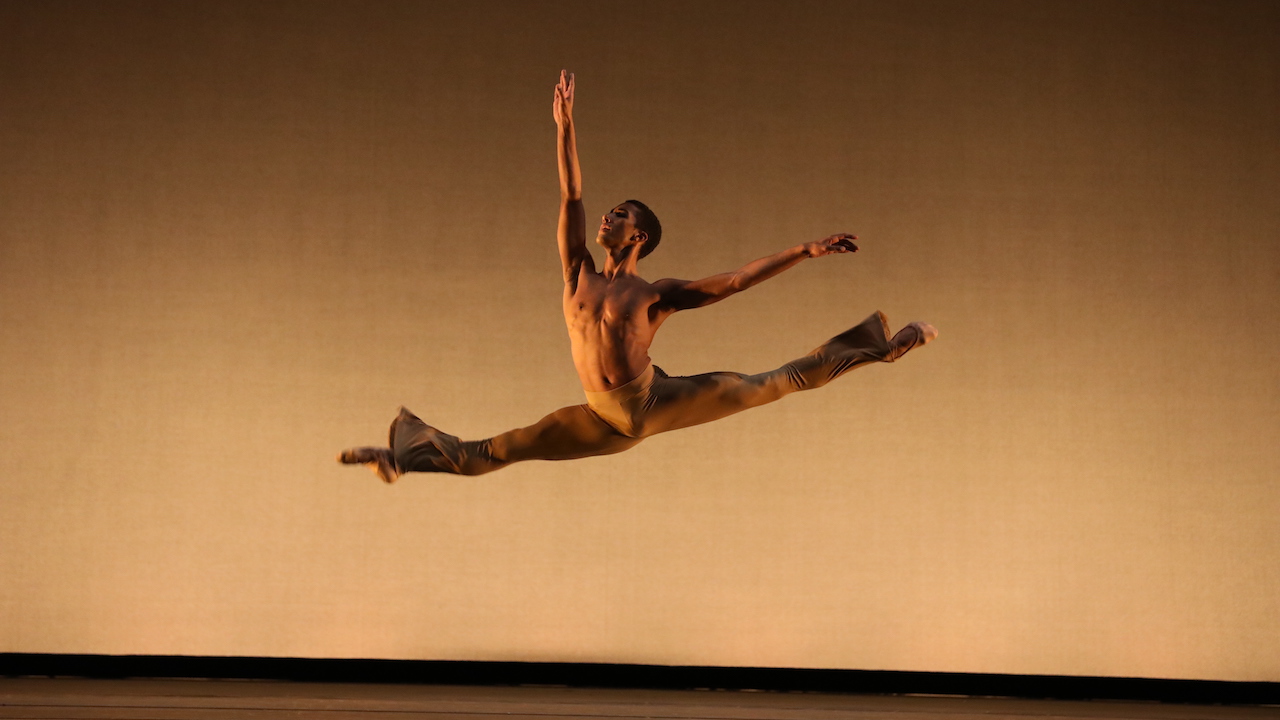

Same sex dancing has found a home across other dance genres. Ballroom culture – not to be confused with the competition genre – while not partner-danced focused has long been not only a refuge, but a very particular expression for queer dancers. Ballroom culture has its own set of dance styles, competitions and is closely aligned with both the Black and Latinx communities, as well as trans and non-binary participants. Immortalised recently in the hit tv show Pose, the ballroom scene in New York City (and later beyond) originated in the late 19th century. An underground subculture of the LGBTQ+ community it is also known as drag ball culture, the house-ballroom community and the ballroom scene.

More than just the dances themselves – though these were important – there was a huge culture around them that rested on the idea of ‘chosen family’ and community. The balls became a space to express through dance and performance elements of culture excluded from traditional dance worlds. Voguing, popularised by Madonna in the early 1980s, had no other traditional ‘home’ in other forms of dance, and only much later did hip-hop began to embrace forms of dance originated at the balls. But beyond the dances too, the communities, the events themselves and the families or ‘houses’, became integral to LGBTQ+ culture in these cities.

Ballroom culture survives and thrives today. Balls are now often aligned with the hip-hop dance world, which has come to embrace many of the styles they created. The scene remains fiercely queer and inclusive; indeed, Wales now has a thriving ballroom scene based in Cardiff, supported by the Welsh Ballroom Community and the Queer Emporium. In September 2020 the Welsh Ballroom Community started a new ballroom scene in Cardiff with guidance from members of the scene in London and the international community.

All of this activity constitutes a wonderful, thriving and LGBTQ+ inclusive pocket of dance. But obviously, if you don’t know it exists, you can’t access it. That’s why the visibility of John Waite and Johannes Radebe on Strictly Come Dancing mattered so much. The adage ‘you can’t be what you can’t see’ holds true; while dance spaces may have long existed for queer folks and same-sex partnerships, people need to know they exist. Without being already connected to dance or to a queer community that includes dance, how are queer folks supposed to know that spaces – and permission to dance outside the binary – exist? Representation is vital. As Canty says, ‘the inspiration of John and Johannes on Strictly may lead all sorts of people – including those with body shapes and identities not usually welcomed into such disciplines as ballet – to want to dance. Welcome everyone, encourage everyone, celebrate everyone.’

Watch

Johannes Radebe and John Waite in the final of Strictly Come Dancing

Emily Garside is a writer specialising in queer performance and media. She has a PhD on representations of aids through performance, and her books span Angels in America to Schitt’s Creek. She is also a theatre critic based in Cardiff.

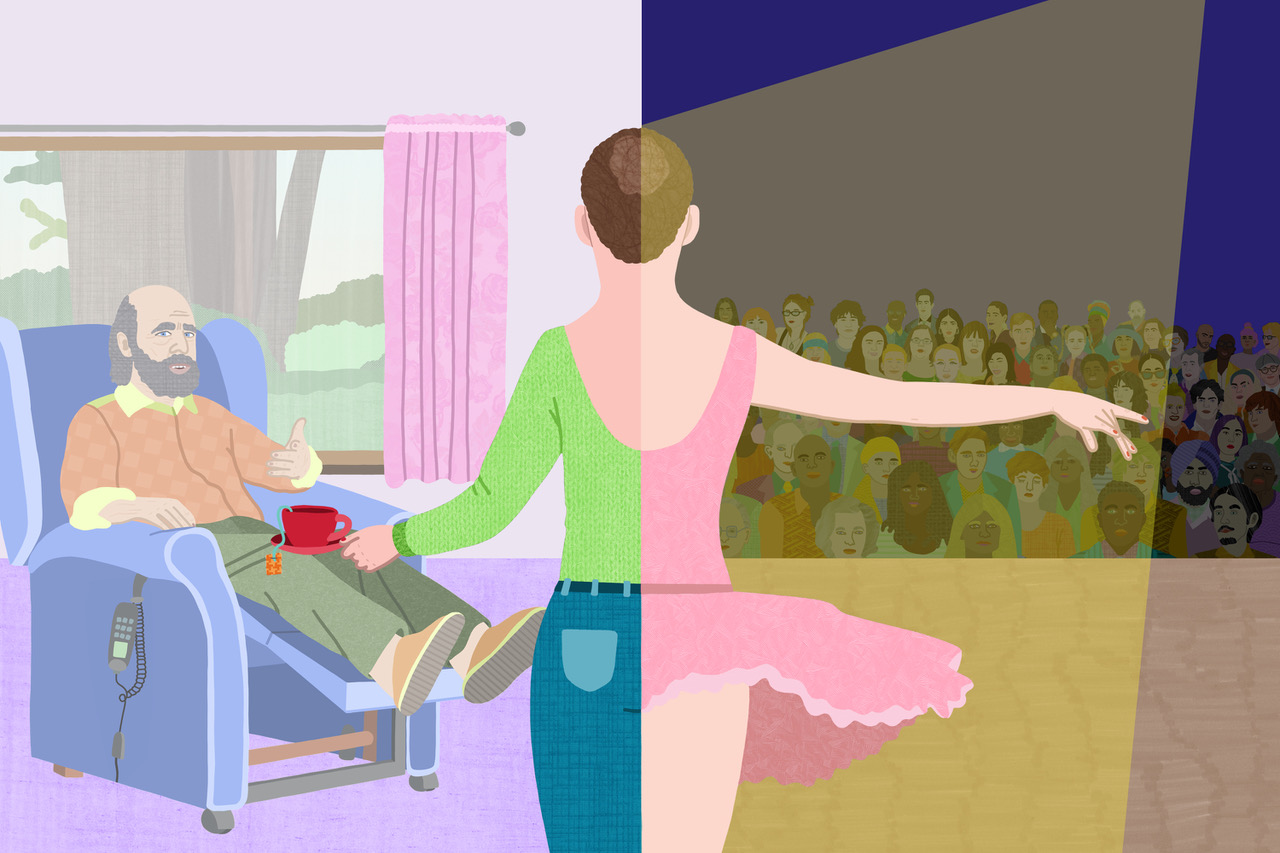

Barbara Gibson is a Polish freelance photomontage illustrator and self-taught artist. She is co-owner of Gibson Kochanek Studio which she runs with her partner. barbaragibson.pl