As a ballet mum of a Muslim background, when I started taking my daughter to classes and performances, I felt a growing awareness that often we were the only ones of our faith there. As we went up the grades, my awareness of this lack of representation has only grown.

While we have never once felt uncomfortable or marginalised, and have been lucky enough to have a wonderful teacher, I sometimes find it difficult to shake off a sense of absence and loss – for a generation of girls like my daughter for whom their faith is a central part of their identity and values, and who would love to enjoy ballet but are missing out.

I couldn’t help wondering: where do these barriers come from? Is it from the community or the ballet industry – or is a generation of potential young dancers being lost in the space in between? What I did feel for certain was that for girls of a Muslim background, there are two glass ceilings to break – one within the community and one within the ballet space.

The lack of Muslim girls in the ballet space has been the elephant in the room for some time. While there isn’t much formal research into the issue, perhaps we can see parallels with the sports world which has grappled with similar issues. Great strides have been made but we still find mixed messages: for example, during the Olympics we saw elite sportswomen in hijab winning gold while simultaneously seeing a ban on hijabs by the host nation, France

On a grassroots level, research by Muslimah Sports Association, England’s largest Muslim women’s sports charity, revealed that Muslim women from lower social economic backgrounds were the least likely to take part in any organised physical activity outside the home. Their survey found 97 percent of women did want to take part in sport, but nearly half felt current facilities were not faith appropriate. Perhaps the figures are similar for ballet?

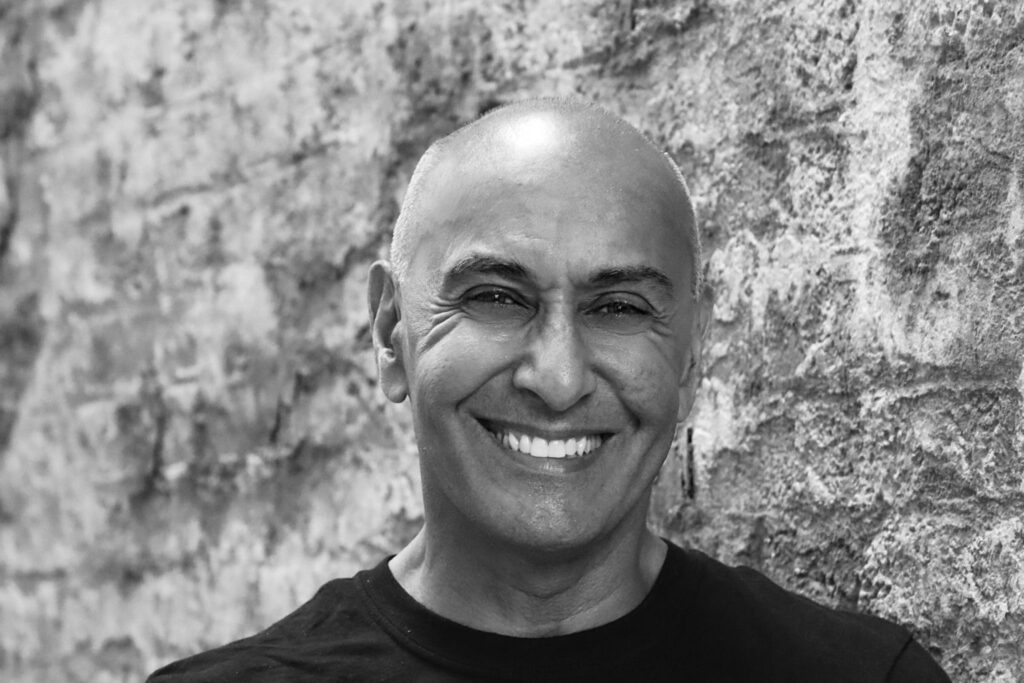

‘It’s not that dance is an issue in itself – a lot of Muslim girls do kathak [traditional Indian dance] and Bollywood dance,’ says Farooq Chaudhary, Producing Director of the Akram Khan Company. ‘A key issue is body exposure and there’s a lot of physical contact. Ballet is primarily designed around a western body and clothing is an extension of that.’

‘It’s a complex mix: lack of role models, physicality, religious views around body exposure’

Farooq Chaudhry

‘There’s never just one reason,’ he adds. ‘It’s a complex mixture of lack of role models, physicality and religious views around body exposure. Culturally, there’s also a focus on academics [in Muslim families] – my dad didn’t speak to me for 10 years when I decided I wanted to be a dancer.’

For Muslim girls who do ballet, there seems to be a high drop-out rate when girls reach puberty as their religious requirements change. Some girls may choose to wear a hijab or more modest clothing, and become more conscious of prayer routines or mixing with the opposite sex. These values can conflict with ballet’s demand for figure-conscious clothing, particularly during exams and performances.

Even for families who are less religiously practising, clothing can be problematic. I consider myself fairly liberal, but found myself grappling with these issues. As religious values play an increasingly central role in a dancer’s life, they begin guiding your choices: whether you can take part in a performance due to the costumes or stick to a class certificate rather than a graded exam because of the dress code. As students approach advanced levels, issues around partnering and the tactile nature of performance become major stumbling blocks. Some girls may take the decision that it’s easier to just leave ballet altogether.

‘Ballet is built on the grading system,’ says Chaudhry. ‘You have to dress a certain way and perform certain dances. As physicality takes on a different meaning for girls, it becomes a place of observation, intensified by social media. For Muslim girls, there is an added dimension to that.’

Like many mums, when Batool Zahra from London excitedly enrolled her daughter into ballet classes when she was five, she didn’t ponder the religious implications. Now that her daughter is 10 these considerations have come to the fore. ‘It was only as she got older that I began to realise the possible implications,’ Zahra explains. ‘She is thinking about wearing hijab soon – it would not fit in with the ballet dress code as she will cover her hair and body.

‘I always encourage my daughter and wouldn’t want her to think she couldn’t pursue ballet due to her beliefs. Although rare, there are ballerinas who have adapted their hijab to fit in with ballet and to follow their religion. If this can be incorporated into novice ballet, it will encourage girls to pursue it for longer. We’ve seen professional sports accommodate Muslim women wearing hijab and it would be great to see this in other areas. Segregated ballet classes may also make young girls feel more comfortable.’

‘I wouldn’t want my daughter to think she couldn’t pursue ballet due to her beliefs’

Batool Zahra

In more conservative communities, the clothing and tactile nature of dance can often mean that girls can face barriers. ‘When I became Muslim I continued to dance for a while,’ said Weronika Ozpolat a former semi-professional dancer, ‘but even though I covered up, I got so much negativity from other Muslim women. I even tried setting up a dance class just for Muslim women but soon stopped because of the negativity.’

‘When I had my own daughters,’ Ozpolat continues, ‘I let them dance because my religious views were less strict. Dancewear is problematic because it’s so revealing and tight. My six-year-old currently does ballet and if she still does it as a teenager, the clothing is going to cause issues. My 14-year-old gave up out of her own choice and now does street dancing – the clothing is so baggy and covered, it’s much more appropriate.’

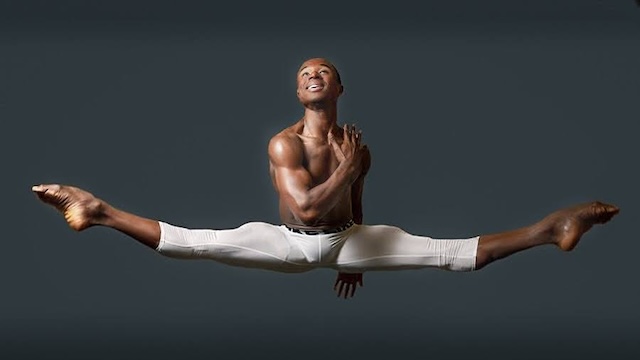

Ballet clothing has already been under scrutiny as part of a wider conversation around diversity and inclusion. There have been campaigns for ballet tights and pointe shoes in diverse skin tones. Misty Copeland, American Ballet Theatre’s first Black female principal, has said, ‘when you buy pointe shoes or ballet slippers, and the colour is called European pink, it says: you don’t fit in, you don’t belong.’

The debate around dance wear highlights the lack of inclusivity in dance overall. Could inclusivity be expanded to faith groups? What would inclusion look like for Muslim women? And how do we make ballet spaces open to communities who may not see them as a safe or welcoming?

In western society, there is a perception that the Muslim community don’t ‘do’ ballet. But many girls for whom their faith is a central part of their lives also want to enjoy ballet without compromising those values. Minor adjustments, such wearing leggings for classes, can have a major positive impact.

It is possible to bridge the gap of understanding between the Muslim community and the ballet space. Faith was not a barrier to the Australian dancer Stephanie Kurlow, often described as the world’s first hijabi ballerina. (In 2022, Kurlow announced on Instagram that she had decided to stop wearing the hijab, saying ‘at this point in my life it isn’t such a strong part of my visible identity.’)

‘What does inclusion look like for Muslim women? How do we make ballet spaces safe and welcoming?’

In London, Grace and Poise is the world’s first ballet school catering to the needs of Muslim students, with a faith-friendly curriculum which doesn’t compromise the demands of classical ballet. It was the brainchild of RAD trained Maisie Byers who was inspired by her own journey to Islam as a covert. She wanted to make ballet more accessible, particularly to the Muslim community. ‘In the past, accessing ballet was a difficulty for many in the Muslim community,’ she says. ‘It seemed the only path for them to access ballet would involve compromising their values. Fortunately we have been able to fill that gap. We are revolutionising ballet and hope that our approach will be celebrated as an Islamic art form within Muslim communities.’

The school follows a carefully curated curriculum which instead of music uses poetry, written by Byers herself. This draws on the musicality and natural rhythms of language, and harks back to the oral tradition of the Islamic faith. The school also has a strict policy on mixed environments. ‘People are surprised to hear that we are like any other ballet class,’ Byers explains. ‘As we have a strict segregation policy, our teachers and students are free to remove their hijabs and wear leotards like every other dance class.’

That may the key. Muslim girls are just like any other dancers who want to learn and love their craft – but they want to do it in a way that fits in with their beliefs. ‘The willingness in the Muslim community is there,’ says Chaudhry, ‘and will grow if we can give it the confidence to be supported.’

Alia Waheed is a freelance journalist specialising in issues affecting Asian women in the UK and the Indian subcontinent.

Fahmida Azim is an illustrator and author who won a Pulitzer Prize for the comic I Escaped A Chinese Internment Camp. Her new book, Djinnology: An Illuminated Compendium of Spirits and Stories from the Muslim World, has just been published.