Deborah MacMillan has strong views on the way that her late husband Kenneth’s choreography should be transmitted. ‘You’d never tell a musician, just play what you remember. Or ask a conductor to conduct a score like someone else. But that’s what can happen if dancers start absorbing what they see on the internet and thinking that’s what the choreographer wanted. Or if coaches teach the ballet they remember.’

For many years, she has specified that if a company wants to perform a MacMillan ballet, it must be taught from the score recorded in Benesh notation. This collates the version of the work closest to what MacMillan wanted, adding changes and adaptations used down the years. It is not set in stone. ‘It can’t be mechanical. It will be dead if it is, stuck in aspic. It’s got to be a living thing. But you go back to the score each time.’

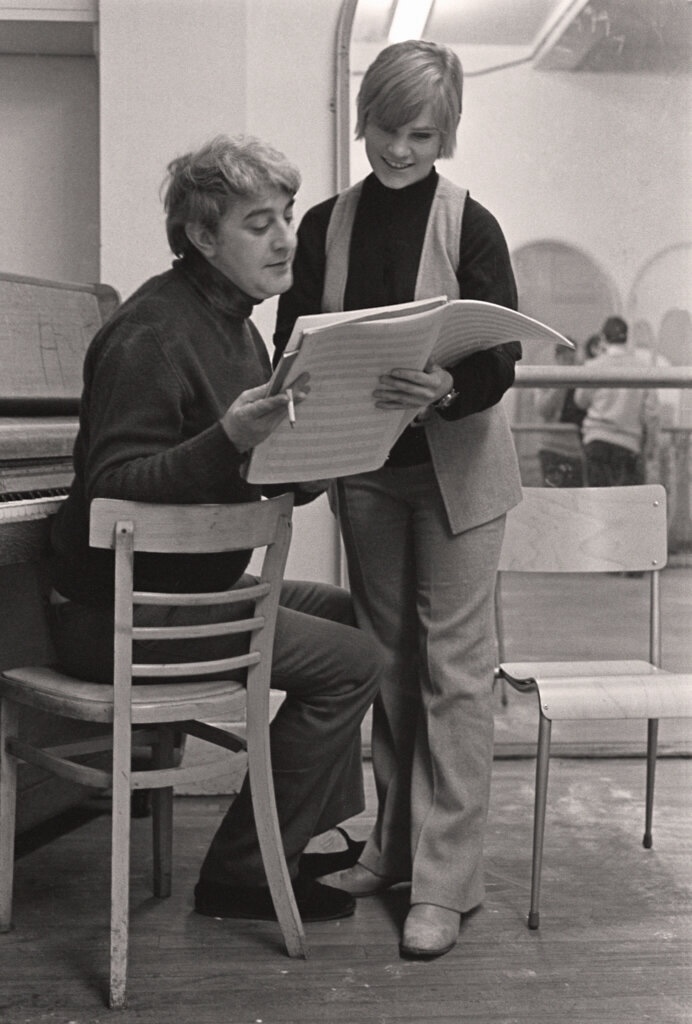

‘At its heart, Benesh is simple. Just three basic signs, that’s the beauty of it’

Melanie Simpkin

In the mid-1950s, the system of notation invented by Joan Benesh, a former dancer, and her husband Rudolf, an accountant and artist, felt like the future. It was a way of preserving movement – that most ephemeral thing– on paper in the same way as music. It took a musical stave as its inspiration, each movement recorded like a cartoon strip, with marks indicating the position of the dancer’s body, the place and direction of each step.

The first full example, written by Joan Benesh herself in 1957, recorded Fokine’s Petrushka. In 1960, Faith Worth became the first choreologist employed by the Royal Ballet, charged with recording existing repertory and notating new ballets as they were commissioned. Both Frederick Ashton and MacMillan were enthusiastic adopters; choreologist Monica Parker sat at MacMillan’s side for most of his working life, notating everything he made.

CHK Benesh Movement Notation (BMN) looks complicated. But Melanie Simpkin, Head of Benesh International (part of the RAD), says: ‘At its heart, it’s very simple. It’s just three basic signs, that’s the beauty of it. Three concepts. Anything that happens in front of the body, anything level and anything behind. Once you break it into manageable pieces, it is possible to read and understand after a 15-minute session, though group and floor work are more complicated.’

BMN records a dancer’s position on a stave that reaches from the top of the head to the floor, and the five lines of the stave correspond to head, shoulders, waist, knees and floor. ‘A full Benesh score looks a bit like a music score, with a line of notation for each cast member,’ says Simpkin. ‘Essentially you start at the left-hand side of the page and read across. The stave is divided into individual frames, like a frame of film. Movement lines show how you get from one position to the next. Anything to do with timing or rhythm or dynamics is recorded above the stave, and below it we record location or changes of direction.’

Simpkin studied Benesh as part of her dance degree at Surrey University. ‘It made sense to me instantly.’ Now she aims to encourage awareness and develop courses at the RAD to help choreologists and notators of the future. The beginners’ level enables teachers to read notation, including RAD exam exercises; the next level is designed for people who want to lead rehearsals or work as a ballet master or mistress; while a full choreologists’ course trains people to work professionally within companies, notating new works or reconstructing pieces from an existing score.

‘The further you get from a ballet’s creation, the more flaky memory becomes’

Jeanetta Laurence

But if Benesh seemed useful when video technology was in its infancy, why bother promoting it when every step can easily be recorded on film? ‘Video will never replace notation because it is a single performance, one interpretation on the day,’ says Simpkin. ‘Anything can happen during a live performance. People may drop something, slip or turn the wrong way. A video doesn’t give nuance or explain the imagery behind a certain move – which is recorded in the notes of a full notation. The notated score is the blueprint of what a ballet should be.’

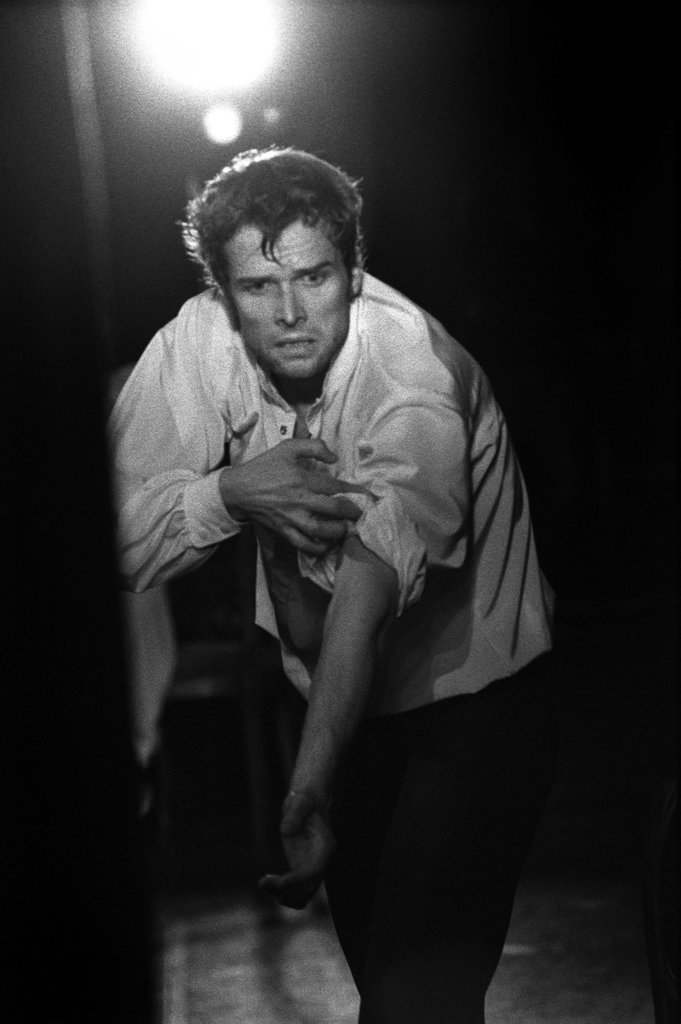

As a principal dancer with Stuttgart Ballet and the Royal Ballet, Robert Tewsley danced many MacMillan roles, including Romeo, Rudolf in Mayerling and Des Grieux in Manon. Two years ago, Deborah MacMillan asked if he would take the Benesh choreologist course in order to stage the ballets. ‘It is such a logical way of working,’ he says. ‘You can capture so much more within notation. The master score for Manon, created by the late Karl Burnett, is a work of art. On one side is the notation and the opposite page contains notes, different versions and explanations of each character. Reading it is inspiring, you don’t need a video. You can see it on the page.’

The Ashton Foundation also emphasises notation when staging Ashton’s works. Its chair, Jeanetta Laurence, says: ‘Film is a vital part of the tool chest. But you can’t see the work from every angle and it’s a snapshot of a particular performance. The further you get away from the creation, the more flaky memory becomes. The only real record of a ballet you can look at is the notated score.’

The Foundation has set up a shadowing scheme to produce the next generation of repetiteurs for the Ashton canon. Some, like Samara Downs, have reached the highest level of choreology. She recently taught La Valse (notated in 1977 when Ashton was still alive) to Royal Ballet School leavers for their summer performance. ‘She’d never danced in the ballet, and she put it on brilliantly,’ says Laurence

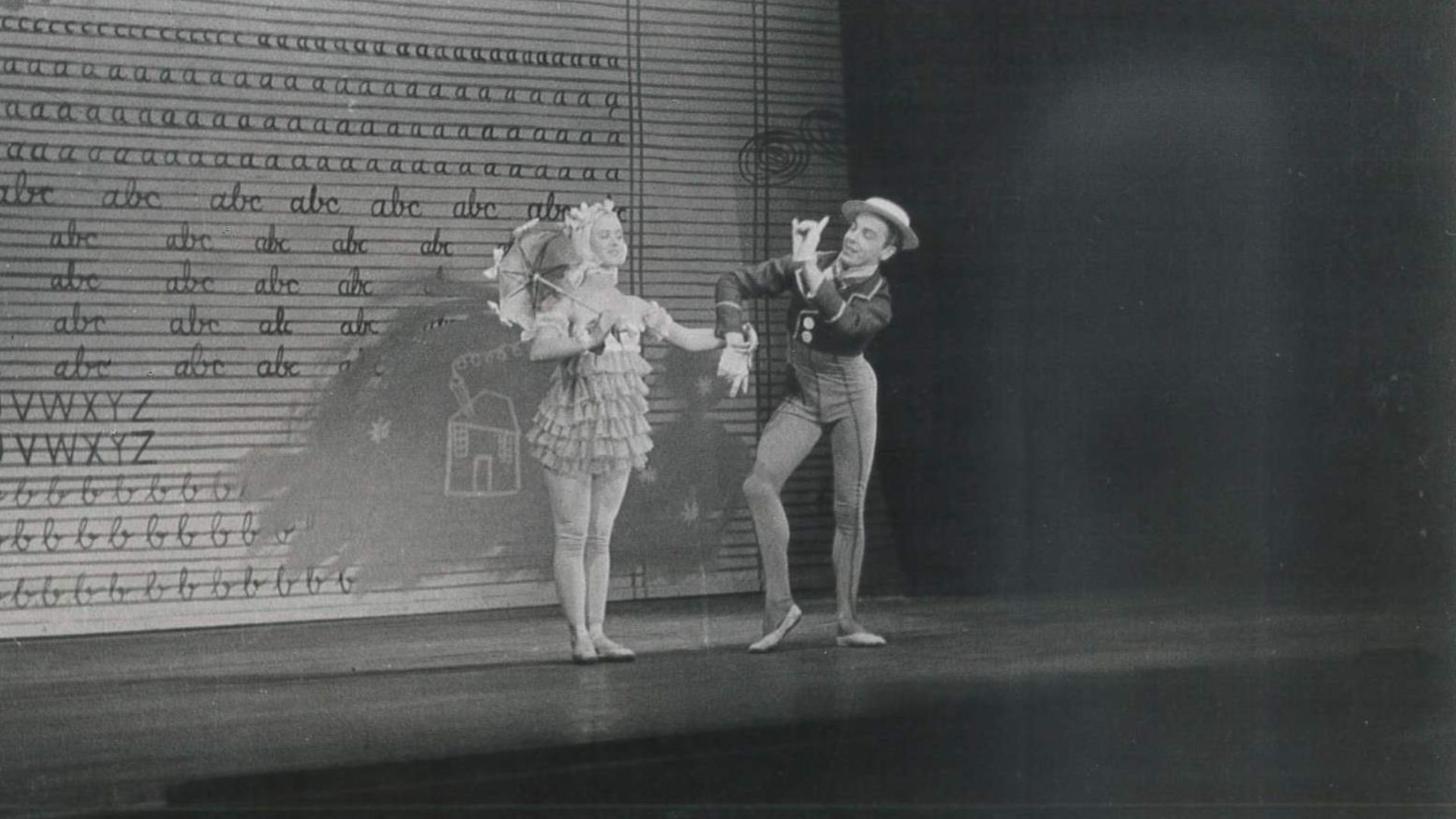

The notated score was also used in the Royal Ballet’s recent revival of Les Rendezvous, first seen in 1933 and recorded in 1964 by Faith Worth and Christopher Newton. Lynn Wallis, former Artistic Director at the RAD and a trustee of both the Ashton Foundation and Benesh Institute Endowment Fund, was among the team behind the staging by Vanessa Palmer.

Wallis first learnt to read Benesh as a student at the Royal Ballet School, and then took private lessons. ‘When I am staging Ashton ballets, I do all my research before the first rehearsal,’ she explains. ‘My main point of reference is the Benesh. I also look at dvds, videos, photographs, but Benesh is the starting point. I take my score into rehearsal and refer to it. I don’t want to be making up the choreography on the choreography. If I’m not sure about the angle of a head or the arm position, I’ve got an instant clarification within the Benesh score.’

This clarity is what Deborah MacMillan also values and it is why she too encourages a new generation of dancers to learn to read and indeed write Benesh scores. She also asks that notators and coaches agree outside the room what they are teaching. ‘For a long time notators were treated quite badly,’ she says. ‘They must have the authority to walk into a room full of highly trained professional dancers and be taken seriously. It’s now more than 30 years since Kenneth died – there are umpteen versions of various ballets on the internet, but I want it taught absolutely from the Benesh. They need to learn the Benesh score as if learning a piece of music. Then they can make individual adaptations.’

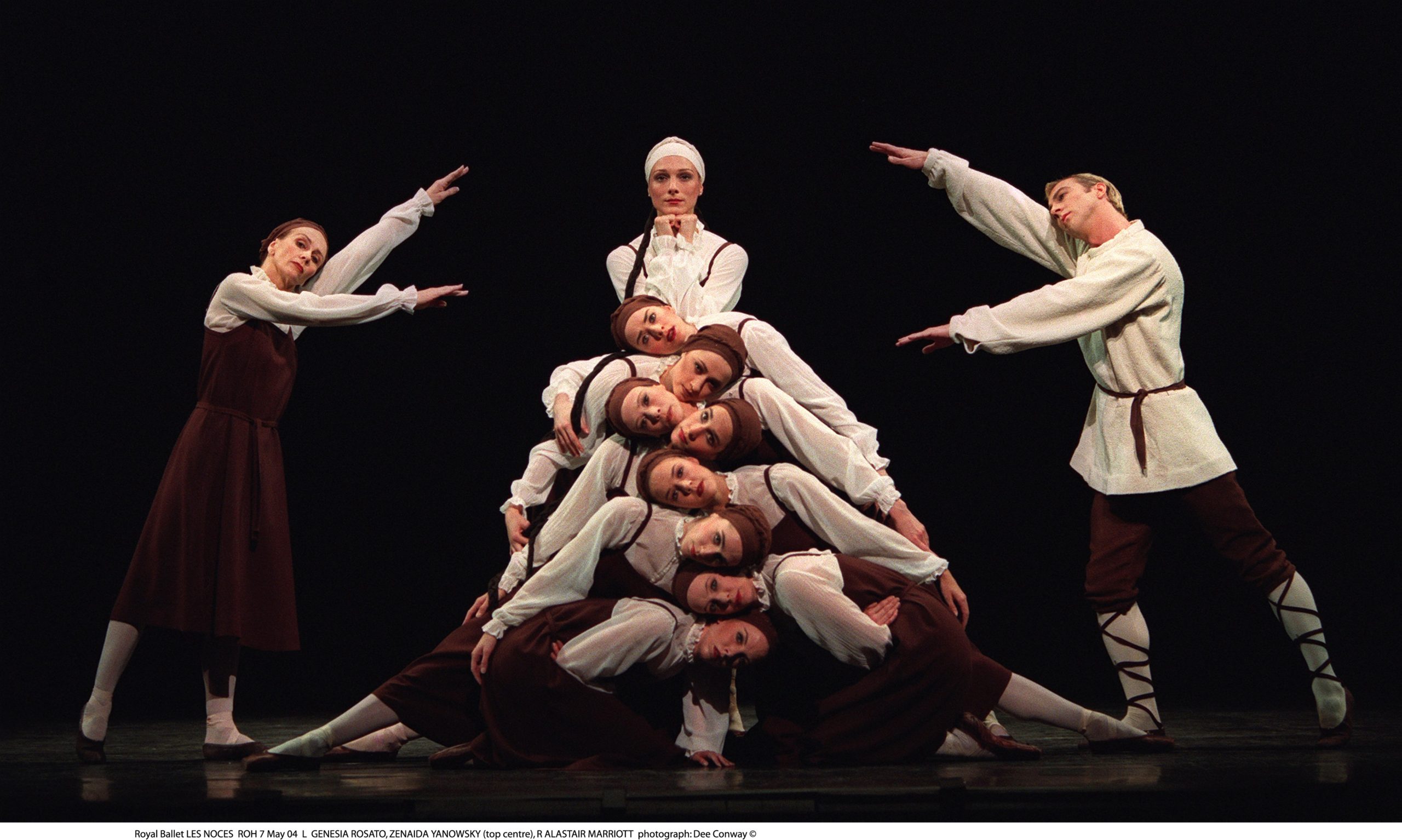

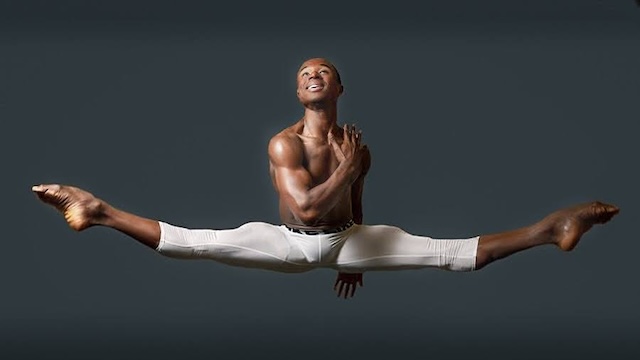

Recently, London City Ballet used BMN to revive MacMillan’s Ballade, made in 1972 but unseen for 50 years. There are 669 scores lodged with Benesh International at the RAD, including many original pencil manuscripts written in the white heat of the rehearsal room. Some works – for example, Lynn Seymour’s Intimate Letters, made for Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet in 1978 – now only exist as a Benesh score. Others, like the notations of Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Biches and Les Noces, made when she staged them for the Royal Ballet in the 1960s, represent the principal record of important historical works (most Nijinksa ballets are entirely lost). The process of recording new works in BMN continues: both Wayne McGregor and Christopher Wheeldon (President of Benesh International) work with Benesh choreologists.

‘People need to learn the Benesh score as if learning a piece of music’

Deborah MacMillan

The choreologist’s art is elaborate and painstaking. Simpkin, who recently notated Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Medusa, explains that they build from rehearsal notes, pencilled on paper and full of rubbings out, into a rough working score, and finally a master copy. Benesh can record any kind of movement, from folk dance to contemporary to the progress made by a physiotherapy patient. The slowness of putting together a master score can be off-putting: Rambert, for example, no longer uses notation, relying on film. Yet Simpkin argues that the advantages of a permanent record far outweigh the laborious process.

In fact, she says, it is an argument for training more choreologists and for companies to give them enough time to ensure a work is preserved. ‘It is utterly worth it. The notation will always be there, long after memories have faded and people have disappeared. Even some of the technology used to record ballets will be outdated eventually. Yet the Benesh score will remain.’

Sarah Crompton is a writer and broadcaster, and dance critic for the Observer.