‘It’s hard to believe. You think maybe it’s fireworks or something. But I could see the fire from my window, and deep inside I realised that something impossible had happened.’

On her usual morning routine involving a 5am breakfast and fretting over choreography for rehearsals at the National Opera of Ukraine, Zhenya Novikova experienced the unimaginable. ‘I was running over the house thinking maybe I need to go to the basement or maybe I need to pack my stuff,’ she says. ‘I called everyone I knew, my family, friends, to see if they were okay.’

In the blink of an eye, Novikova’s world changed drastically: from first soloist at the National Opera to a refugee fleeing Kyiv to find safety. ‘We didn’t know what to do because Russian forces started coming,’ she says, recounting the anxiety she experienced with her husband in their apartment. ‘You don’t know which highway to choose. Is it safe or not? Maybe it’s safer to stay? Maybe it’s safer to go.’

‘I wanted a place to dance and get back in shape. I felt new again’

– Zhenya Novikova

Across our news channels, reports were flying in of thousands of civilians who chose to stay put because they were too scared to leave. Too scared of the unknown awaiting them outside the homes and cities they knew. For Novikova, 38, the choice was made for her and her husband. ‘We heard another explosion very close to our house,’ she says. ‘It was a military plane which fell down. That’s when we decided to go.’

About 300 miles south-west of Kiev, Vladyslava Ihnatenko, 19, was working at the Odessa National Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet when the war began; dampening her excitement to perform in the corps de ballet at the opera’s new season. ‘I was staying in Odessa with the family of a friend,’ she says. ‘It was quieter there, so I almost didn’t hear anything when the war started. I didn’t see my parents because all my family were in Kharkiv. I was there alone, and I was very nervous.’

Following the indefinite suspension of performances, many artists and technical workers of the Odessa Opera joined the ranks of fighters to protect the city. With her family miles away and the threat of conflict approaching, Ihnatenko felt isolated and anxious about her future. ‘I saw that there was no job opportunity, and I cannot go back to Kharkiv,’ she says. ‘To stay there alone was hard so that’s why I decided to leave the country.’

She travelled 450 miles all alone to Lviv, which is by the Poland-Ukraine border. The knowledge that a friend was waiting for her in Poland kept her going. For Novikova, the Hungary-Ukraine border felt the better choice, driving for two days without much food or sleep.

In this state, worries about work, family safety, where to sleep next, and settling in a new country are often all refugees think about. Yet in their tired and fragile condition Ihnatenko and Novikova turned to helping others around them. ‘I was trying to help because not all the people there knew English to speak to volunteers,’ Ihnatenko says. In Novikova’s case, it was important for her to feel ‘useful for my country in some tiny way.’ She lived out of her car at the Hungary-Ukraine border for four months, ‘helping people find shelter in different countries and theatres’.

It’s not so farfetched to see how their profession could be the source of their empathy, giving them something to draw from in crisis. Dance has a beautiful way of bringing people together. ‘I tried to get back to the profession,’ Novikova says, as a way to find herself useful again through the art she loves. Getting people to theatres open to receiving refugees was her way of tying together the power dance gave her with her newfound role at the border.

Turning to dance has definitely made coping with displacement easier for seven-year-old Kira. Through the UK’s resettlement scheme ‘Homes for Ukraine’, Kira was able to find a sense of calm with her mum Iryna in the rural village of Hersham in Surrey. ‘I think she’s happy when she dances,’ Iryna says. ‘In Ukraine, she didn’t study ballet but Latin dances, and she enjoyed it. When she listens to some music she wants to dance all the time. It’s like her nature.’

And it was quite clear. Kira was playful and full of energy after her class at the Joanne Ward Dance Academy. Thanks to their sponsor family, Marie and Steve Williamson, posting on the ‘Walton & Hersham mums’ Facebook group for support, Kira found her way back to dance in RAD teacher Joanne Ward’s ballet class. ‘I told Marie and Iryna to just bring her along whenever, to any of my classes, any time,’ Ward says. ‘I’m just happy to provide a place where Kira can express herself, be free and be able to dance. She really enjoys it.’

LOOK

Kira enjoying dancing with Joanne Ward (and Betty the puppy) in Hersham. Photos: Ali Wright for Dance Gazette

‘I’m just happy to provide a place where Kira can express herself, be free and dance’

– Joanne Ward

Creating this environment of safety, consistency, and fun is an ethos that runs through RAD and its teachers. In her work supporting refugee and asylum-seeking children through ballet in Wales, Shelley Isaac-Clarke realised that ‘in dancing together they not only found ways to have lots of fun, but also to become more self-aware and gain confidence in self-communication.’

‘Dance can be a wonderful way of bringing people together,’ she adds. ‘If we can in any way use the medium of dance to support displaced people, to break down barriers, bring local communities together, be more inclusive, at a time when the world continues to feel so uncertain, we will all reap the benefits of the shared experience.’

Yet it must be so hard to focus on dance, to get lost in the emotion and joy of it after the pain of displacement and war. ‘Of course, it was hard to focus on dancing,’ Ihnatenko says. ‘I guess the main thing is just to be safe from the bad things. But you can just take all of your power, even anger and just put it in dance. It makes it easier.’

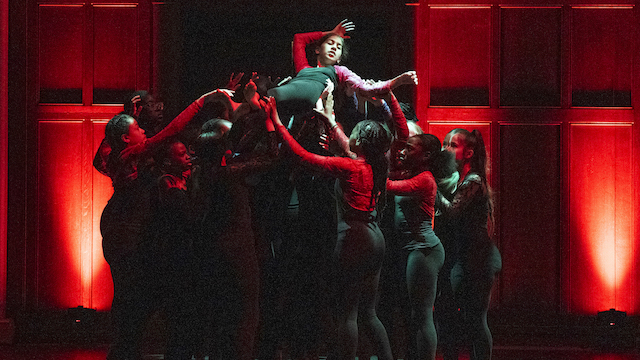

With the support of friends touring to Norway, Novikova made her way across Europe to find a ‘place to dance and get back in shape. It gave me a healing feeling because I felt new again.’ From there, news spread of the United Ukrainian Ballet at the Hague in the Netherlands.

The company was founded to train and employ Ukrainian dancers, creatives, and technicians who fled their country. ‘There were a lot of Ukrainians going so I wanted to join my people,’ Novikova says. ‘I heard that Alexei Ratmansky was going to make work and he’s a legend. So, I applied to be a member of this company and I was accepted.’

Ihnatenko also found her way to the company, reuniting with friends she had lost when she fled. ‘I’m good here because it’s like a community,’ she says. ‘We’re trying to support each other, as we understand each other the most in this case. I was afraid of not being able to dance again but it’s easier now. Having people around you [to focus on dancing again] is helping.’

‘It was hard to focus on dancing. But you can take all of your power, even anger and put it in dance’

– Vladyslava Ihnatenko

With a tour of Ratmansky’s production of Giselle – the renowned choreographer spent his childhood in Kyiv and has been outspoken about the Russian invasion – in the Netherlands and London, Novikova and Ihnatenko have finally been on stage again. Kira will also take to the stage at a local Hersham theatre. But despite the new lives being built, there’s still much anxiety about what their future holds.

‘I guess I’m moving in the right direction,’ Ihnatenko says. For Novikova, it’s one step at a time. ‘I felt unsafe for months after I left the Ukraine,’ she says. ‘I was jumping when a door shut or loud sounds, but here my nervous system is getting stabilised. It’s easier because of dance.’

Kira’s mother Iryna is determined to return to the Ukraine despite her anxiety. But Kira’s voice belting ‘I love dancing!’ melts this tension away. For now, this innocent joy of dance is all that matters.

WATCH

Isaac Ouro-Gnao is a Togolese-British multidisciplinary artist and freelance journalist.