Ksenia Anisimova and her family are making a special stop during their trip to Seoul, the megacity capital of South Korea. The mother of two from New York City, along with her mother and children, visits a dance studio located in a basement of the hip, youthful neighbourhood of Hapjeong-dong. Inside the bright-lit room with its mirrored walls, the family stare back at reflections that reveal a mix of excitement and awkwardness. The seven-year-old son even blushes as he tries to shake off his embarrassment.

The dance instructor blasts on BTS’ Permission to Dance. One step at a time, the family learns routines made famous by the boy band who usually show off their famed ‘knife-like precision dance moves’ in packed stadiums. The unique attraction of this class is that Jeong Soo-min, leading the 90-minute tutorial, has danced beside BTS and other K-pop giants like Blackpink and GOT7 many times before. She’s also a dance trainer at a major entertainment label.

At the American Music Awards in 2021, BTS became the first Asian act to be named artist of the year: a sign that K-pop (Korean popular music) has conquered the world. BTS is also the most streamed group on Spotify and the most followed on Instagram; in 2021 entertainment businesses listed in Seoul earned a record $3.8bn. Popular at home since the 1990s, social media has helped K-pop spread internationally. The music journalist Maria Sherman describes it as ‘a maximalist dreamland full of colour, high concept-performances and videos, a plethora of performers and unrivalled choreography.’

As the name implies, visitors to Real K-pop Dance get to feel like a star. They learn from backing dancers who usually perform alongside favourite groups. In the break, the family chats in Russian. But during the class, language doesn’t pose a problem. Jeong teaches each move with a simple ‘1,2,3,4’ while the students attempt to mirror her.

‘I saw some videos of K-pop groups on YouTube, and I thought it was the most fascinating thing,’ says Anisimova. ‘I had to check it out more.’ She was especially intrigued by the incorporation of sign language in the video for Permission to Dance; back home, she works with students who are deaf or have learning disabilities.

‘When our teacher first showed us what we needed to learn today, we thought we couldn’t possibly do it,’ she says. ‘But we’re able to do most of the general moves now. I would say this is one of the best stops on our tour.’

It’s exactly this tourist appeal that gave Kim Min-sung the idea for his business in 2015, after a career as a backing dancer for K-pop legends like first generation boy band H.O.T. ‘When I was a student majoring in tourism, I remember a news article that highlighted how Chinese tourists were coming to South Korea,’ he recalls. ‘When I looked up their typical itinerary, there wasn’t anything new or exciting.’

He set up shop in Hongdae, a magnet for foreign travellers, lined with glitzy restaurants, bars and shops. ‘Most of our clients are young women in their teens or twenties, but we also have men and even parents coming with their children. A lot come from surrounding regions like China, Japan and southeast Asian countries while many still come from the Americas.’

‘As the stars’ skills keep rising, every label has higher expectations of the students’

– Kim Ji-sun

On top of school work, students spend up to five hours in the studio on weekdays and even at weekends

Today, K-pop is a powerhouse genre with audiences in almost every corner of the world. But this was not the case when Lee made up routines in his room in the late 1990s, as first-generation groups like H.O.T. and S.E.S. introduced the evolving South Korean music scene to a wider public. ‘I was so addicted to H.O.T. that I would constantly watch clips of them at breakfast and as soon as I got home from school,’ Kim says. ‘But I never thought that our country’s music would become a global force in content and culture as it is now.’

The 16-year-old Kim was amazed at how each of H.O.T.’s albums would introduce a whole new visual concept and vibe. The group’s hairstyles featured mint colours, samurai styles, ponytails and dreadlocks. Their costumes were even more out-of-this-world: Edward Scissorhands looks would be followed a few months later by outfits resembling the Teletubbies – cute accessories and all.

‘It’s star quality that separates K-pop from the rest of the field,’ Kim says. ‘Not only do they possess world class vocals and dancing abilities, their visuals are flawless and their styles are among the best in the world.’ On social media platforms like YouTube and TikTok, dance challenges uploaded by K-pop groups rack up millions of views. ‘The dancing style is mixed with hip-hop, popping, house and more,’ Kim says. ‘K-pop doesn’t cling to tradition. It is well-suited to changing styles and adapting to the latest trends in pop culture.’

‘K-pop doesn’t cling to tradition. It is well-suited to changing styles and trends in pop culture’

– Kim Min-sung

The road to glory is only for the very few. Young people hoping to forge a career in K-pop face a difficult path. They typically enter an entertainment company in their teens, honing their skills in singing, rapping, dancing and foreign languages. If they have enough talent and luck, they may be selected to join a group.

One Thursday dinner time, students pack into LP Dance, a multi-story building in the bustling Gangnam district (yes, it’s what the song Gangnam Style was about). Most are girls in their mid teens with long black hair, in baggy sweatpants and sneakers. The chatter in the hallways doesn’t stop for an instant as classmates discuss how they’ve prepared for their monthly evaluation.

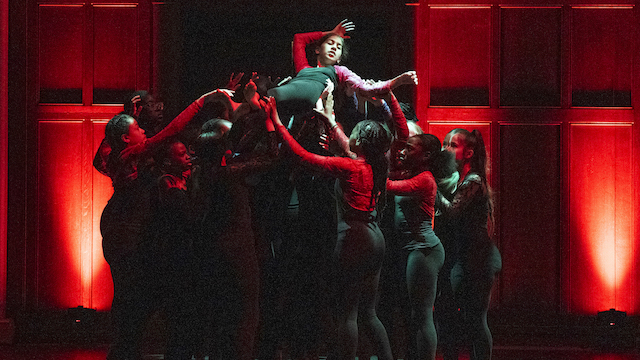

As soon as the doors open, about 20 girls flock into a wide, mirrored studio. The music kicks in and the atmosphere changes instantly: no more laughing or smiling. Girls who looked fragile make the floor rumble with fast, synchronised steps and precision routines. Tiny details like waving fingers before they turn or calculated gazes in the mirror give them the aura of a K-pop girl group. There’s an air of seriousness and competition as the academy’s director enters and surveys the dancers.

In the audition class, where 150 students vie for a place with the entertainment labels that churn out superstars, students are graded on dance and overall appearance, including both facial expressions plus something less tangible. ‘There’s skill, but we also highly regard an entertainer’s star power,’ Kim Ji-sun, director of LP Dance, explains. ‘I look at it as likability, or the ability to make people come back for more. In addition to a great personality, they must be able to incorporate their strengths into their dance so they can make a significant imprint on the eye.’

Each month, top performers win the chance to be filmed for audition clips sent to the entertainment agencies. There are also anything between four to 10 open auditions at the academy where scouts from major labels will critique the dancers. ‘As the stars’ skills in dance, singing and other talents like acting keep rising,’ says Kim Ji-sun, ‘every label has higher expectations of students training at academies.’

Despite this external pressure, it’s the students themselves who push the boundaries of training. South Korea has one of the world’s best-educated labour forces and it’s customary for students to attend after-school crammers and study into the night. On top of rigorous school work, students at LP Dance spend up to five hours in the studio on weekdays and some even come in at weekends. The studios are open seven days a week to accommodate students who come as far from Daegu and Gangneung – each a six-hour round trip from Seoul.

For 16-year-old Lee Seul, the fear that she’s almost too old to become a trainee with an entertainment label drives her to practise even when tired. Kim Suh-jung, also 16, always arrives two hours before class to do strength exercises. After class, he spends another two to three hours honing his dance routines and expressions.

‘K-pop dance gives you euphoria when you hit every beat on cue,’ he says. ‘You can’t help but smile when you’re dancing to some of these songs. As I want to become someone who feels this happiness on stage, practice can’t be taken out of the equation for the sake of my future.’

Even younger students show similar determination. Rahel, 8, is the youngest of the audition group and has assured her mother and the academy that she wants to dance with the big girls instead of students her own age. ‘She found the academy online by herself, telling me that it had the longest tradition, going back 20 years, and was known to host a lot of open auditions,’ says her mother, Lee Seok-hee.

To build her confidence, Rahel takes every chance to dance, and her role model is Jang Won-young of the girl group IVE. ‘As today is the monthly evaluation, we looked at clips of Jang,’ says Lee. ‘Even as we left the house, Rahel kept practising facial expressions in front of the mirror.’ Rahel takes a deep breath, does a final stretch and enters the room to pursue her K-pop dreams.

Watch

David D Lee selects five groundbreaking K-pop dances

David D Lee is a freelance reporter based in Seoul, writing for South China Morning Post, Vice Asia and others.

Jun Michael Park is a documentary photographer and filmmaker from Seoul. He contributes to the New York Times and Monocle.