In November 1922 the Ballets Russes settled for the winter in Monte Carlo. After an August layoff that left many dancers stranded without pay and a seven-week tour in September and October, it must have been wonderful to say goodbye to trains, one-night stands and uncertain salaries. A playground for the rich, Monte Carlo was the jewel of the Riviera, with mild winters, blue skies and hillsides dotted with villas. With her family now beside her, Nijinska had much to look forward to.

For years Les Noces had been in the Ballets Russes pipeline, announced, promised in contracts, and then put off to another season. The idea for the ballet came to Stravinsky shortly before the premiere of The Rite of Spring, and in many ways it remained a close relation of Nijinsky’s masterwork, transformed by a decade of upheavals. Choreographers had come and gone, along with orchestrations and sets of designs for costumes and scenery. Over lunch at Prunier’s in March 1922 Diaghilev told Nijinska that he wanted her to choreograph the new ballet. After bleak months in London improvising in a rented Bloomsbury room, the news ‘burst upon [her] like a ray of sunlight.’ After lunch they went to Stravinsky’s Pleyel studio where for the first time she heard him play the music of what became her most memorable work. ‘The music of Noces astounded me,’ she wrote many years later, ‘overwhelming me with its disturbing rhythm. Les Noces seemed to me to be deeply dramatic, interspersed with occasional splashes of joyousness and true feeling of Russia: At that moment I saw the picture of Les Noces and my choreographic line for the ballet.’

After this transcendent experience, Diaghilev took her to the studio of the ballet’s designer Natalia Goncharova. On the artist’s long work table were dozens of costume sketches, ‘admirably drawn, magnificent colours, theatrical and sumptuously Russian.’ It was definitely not how Nijinska imagined the ballet, and in no uncertain terms she announced this to Diaghilev. In her view the dance costume was a functional garment that took part in the choreographic action and followed the movement of the dancer’s body, which these costumes did not. Moreover, they did not ‘respond’ to Stravinsky’s music. However, Diaghilev had approved the designs, as had Stravinsky. Miffed, Diaghilev took back his offer.

In 1936, Nijinska spoke to the New York Times critic John Martin about the interrelated problem of the ballet’s libretto and design: ‘I debated this point with Diaghilev for a whole year before he consented to my interpretation… To interpret the libretto as the merrymaking of Russian peasants against a pictorial background of sheer exuberance and unalloyed joy would serve to defeat the inherent tragedy.’

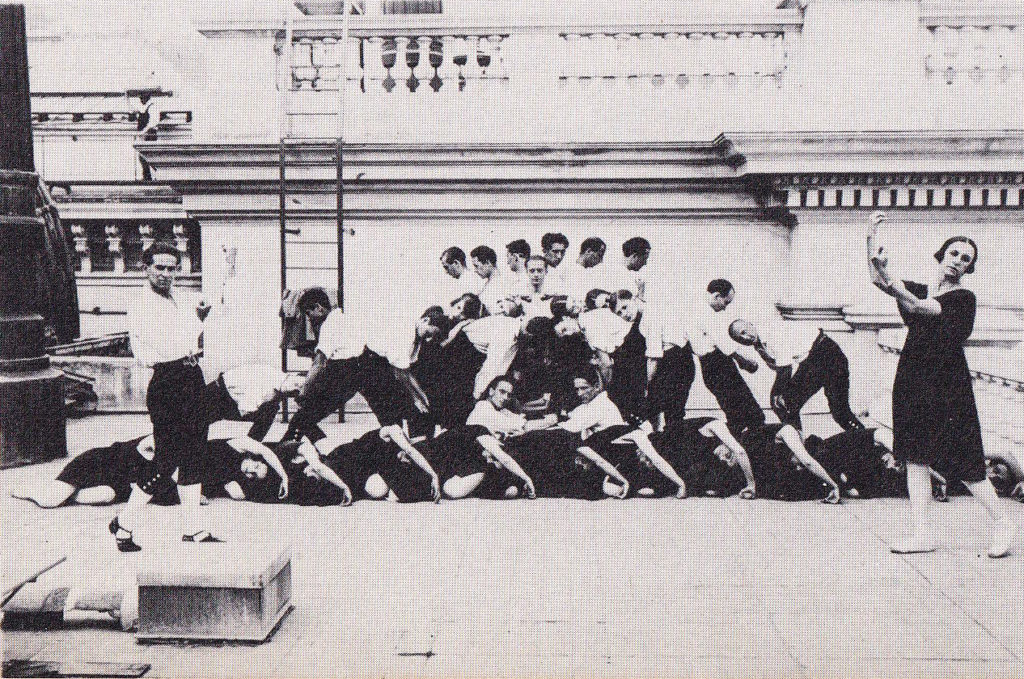

Once rehearsals began in March 1923, the dancers were at it six days a week. Days were long in the Diaghilev company. They began with class, which Nijinska now taught, dressed as always in a blue tunic, followed by two or three rehearsals, depending on whether the company was performing. On matinee days, the second rehearsal took place from 9 to 11 at night.

At the end of April the number of daily rehearsals doubled. By then, the company was in performance mode. On June 1 the dancers arrived in Paris, and in the days leading up to the gala opening on June 13 at the Gaîté-Lyrique they practically lived in the theatre, where class began at 9 a.m. Tempers were short. The theatre, which nobody liked, stood at the northern edge of the Marais, the centre of the garment industry, far from fashionable precincts to the west. Classes were held, Lydia Sokolova tells us, ‘in a long, bleak room at the top of the building, with a barre down one side.’ The morning music rehearsals were shrill and chaotic, with Stravinsky hurling orders and the conductor Ernest Ansermet displaying ‘the patience of a shepherd.’

‘The news about Les Noces burst upon me like a ray of sunlight’

Bronislava Nijinska

Like many Stravinsky works conceived during the 1910s, Les Noces was sung. Stravinsky himself wrote the text, about a peasant wedding set in old Russia, gradually transforming it into a scenic ritual and tragedy, a ballet-cantata fusing music and movement. His quest for ‘ethnographically reliable and unmediated sources’ of folk music led him to some of the earliest transcriptions from phonographic field recordings of Russian wedding songs and wedding and funeral laments, as well as to what the musicologist Margarita Mazo has called the ‘phonemic approach’ to wordsetting. This meant, in the words of a critic paraphrasing Stravinsky, that the ‘words do not combine to make logical sense [but] are arranged… according to their sonorous and rhythmic potential.’ Stravinsky also insisted upon its modernist character, linking its use of language to James Joyce’s Ulysses, published only a year before the ballet’s premiere. Both works, he explained, ‘are trying to present rather than to describe.’

In March 1921, Nijinska had envisioned in her diary a new form of opera, a ‘theatre of action’ with the texts crossed out and the focus shifted to the music. In an article published in the Dancing Times in 1937, she wrote, ‘Noces was the first work where the libretto was a hidden theme for a pure choreography; it was a choreographic concerto.’

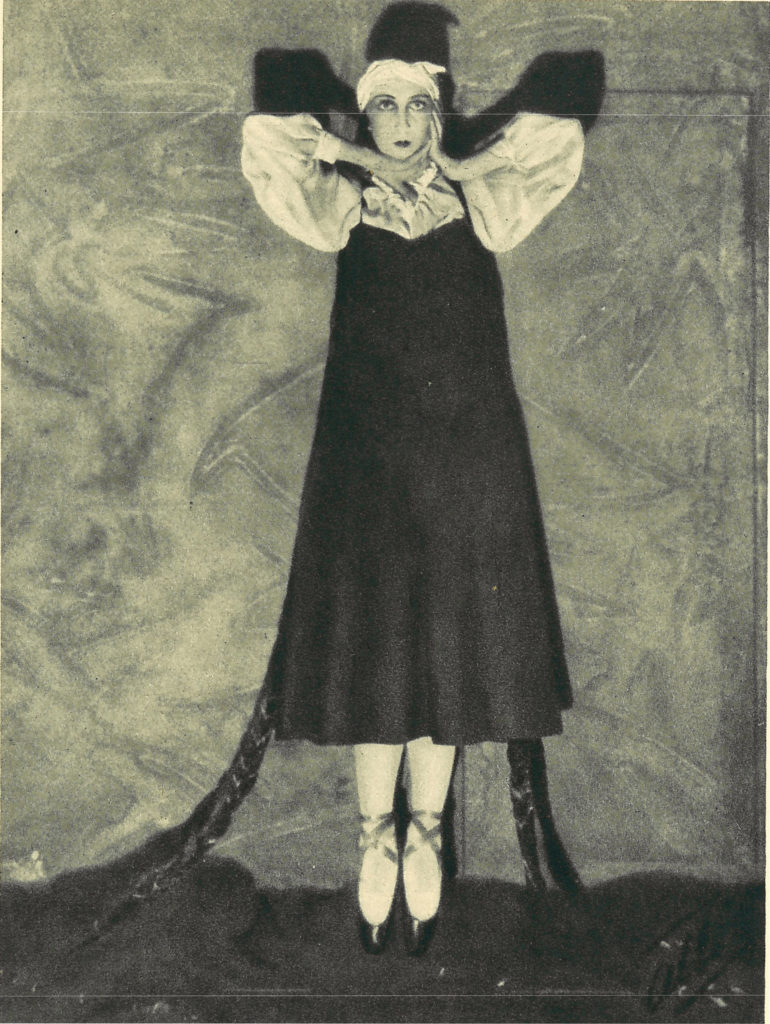

The work had four episodes: At the Bride’s House, At the Bridegroom’s House, The Departure of the Bride, and, finally, The Wedding Feast. In the first, eight women dance with the Bride’s eight-foot-long braids, winding them around her neck as if strangling her. In the second, eight men surround the groom with lusty if highly stylised folk dances. The wedding party leaves the stage in the third, as the Bride’s mother laments the loss of her daughter. Finally, in the fourth, the guests carouse while the newlyweds are sent to bed by their parents.

There is no actual scenario, only a handful of stage directions. As for Stravinsky’s sung text, this Nijinska ignores almost entirely. Its images of nightingales and matchmakers, rings of gold, white swans a-swimming and ribald guests find no echo in her choreography, which drives forward propulsively like the rhythms of Stravinsky’s score, shorn of folklore and the picturesque, as plain as Goncharova’s drab, uniform costumes.

Nijinska never referred to her as such, but her Bride is an artistic cousin of Nijinsky’s female victim in The Rite of Spring. Both are chosen and compelled to serve; each enacts a ritual she cannot escape. To be sure, the Bride’s plight is comparatively benign: unlike the Chosen Maiden, she does not die a violent death. But she still remains a communal victim, her body used, abused, and violated. As Nijinska wrote: ‘I saw a dramatic quality in… the fate of the bride and groom, since the choice is made by parents to whom they owe complete obedience – there is no question of mutuality of feelings. The young girl knows nothing at all about her future family nor what lies in store for her… From the very beginning I had this vision of Les Noces.’

‘As a spectacle, it shatters all laws and stands apart from all known ballets’

Paul Dukas

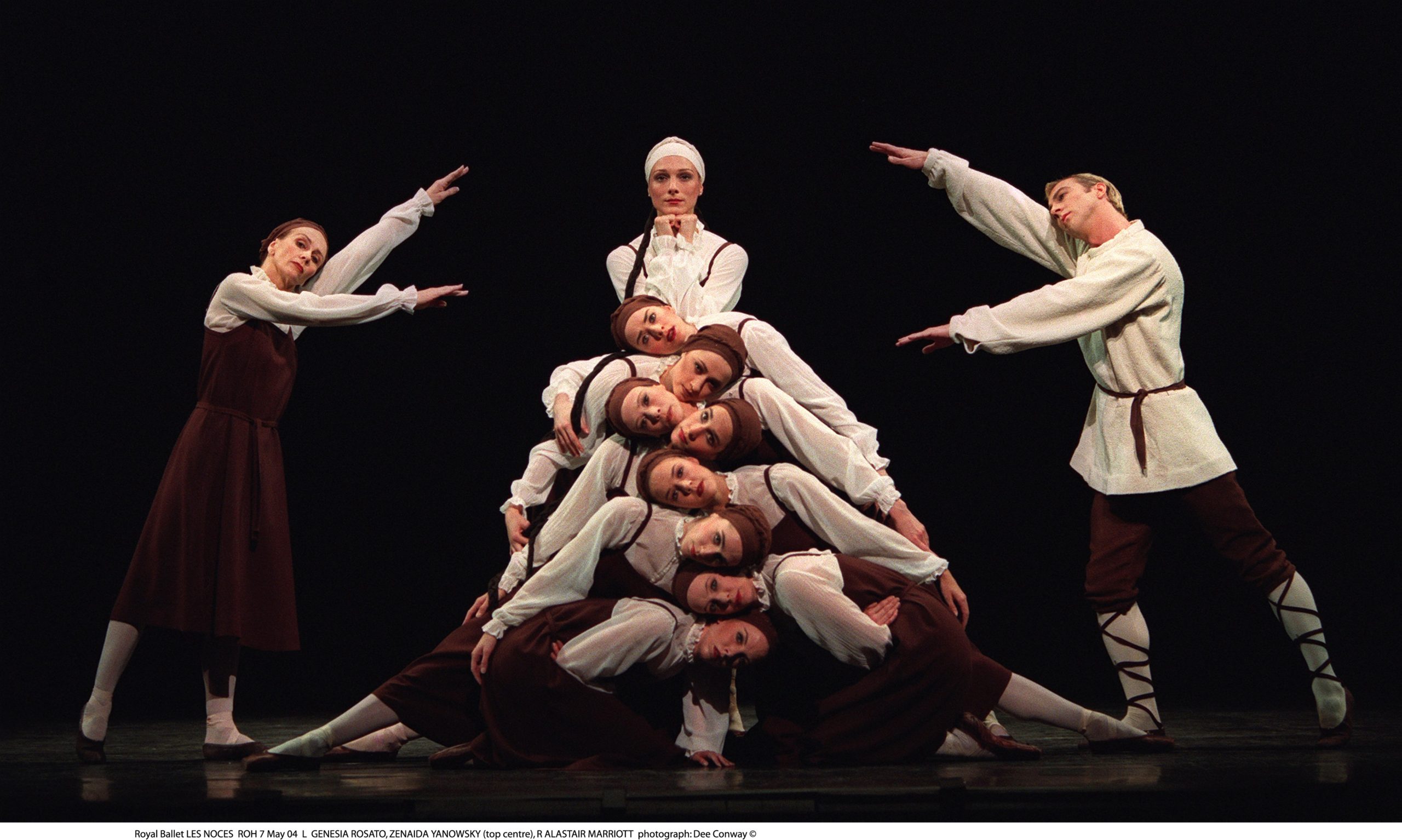

In the final lines of the text Stravinsky celebrates the first passionate embrace of the newlyweds. Onstage, to the tolling of bells and with the slowness of a familiar ritual, the dancers assemble a complex human pyramid – a gendered architecture built from the blocks of same-sex figures that appear earlier in the ballet. At the centre stands the column of ‘braided’ female heads from the end of the first tableau, surmounted now by a new Bride-to-be, while men fan out on either side and prostrate themselves. At the last moment, the new Groom-to-be is hoisted to the apex of the pyramid. Then the curtain falls. What has just transpired is not a unique event, but a ritual that repeats itself again and again.

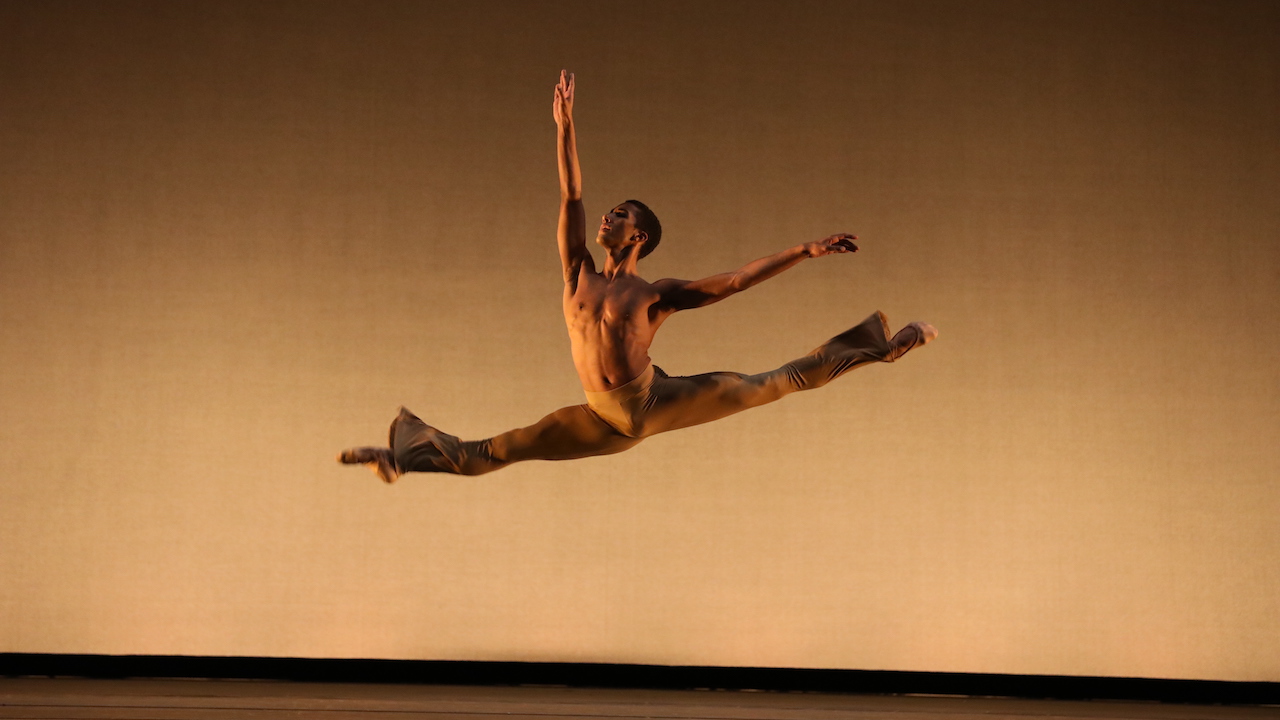

Like the music, the choreography builds on structural blocks. Its movement vocabulary came from the danse d’école but also from the lexicon of Russian national dance forms. Thus the skittering of the women rests on bourrées and pas couru, some of ballet’s oldest steps, while the squat steps of the men evoke a Ukrainian hopak. But nothing is quite right: the women may be on pointe, but they never turn out; the men jump, but never hover in the air. Instead, they hug the ground, hunched over even in jumps with fists to their ears, like dumb beasts of burden. Much of the work is in unison, and often it appears mechanical, with every gesture and every element of a gesture performed with equal weight and occupying an equal unit of time. Large blocks of movement are repeated, not exactly, but with enough identical elements to create the impression of a monolith, as at the end of the second tableau where repeats of the wheeling runs and jumps build to a powerful climax.

The 1923 season at the Gaîté-Lyrique was short. There were eight performances, crammed into nine days. The premiere of Les Noces was a triumph, and Stravinsky, Nijinska and Goncharova all took bows. For the composer-critic Paul Dukas, it was a strange and powerful work, perhaps ‘the strangest and most powerful we have ever seen and heard’ from the Russians. ‘As a spectacle, it shatters all laws, defeats all classifications, and stands wholly and deliberately apart from all… known ballets… This wedding is the funeral song of the saddest Humanity.’

This is an extract from La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern by Lynn Garafola, published by Oxford University Press. oup.com

Watch

Les Noces, filmed in 2001.

Lynn Garafola is Professor Emerita of Dance at Barnard College, Columbia University. A dance historian and critic, she is the author of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and Legacies of Twentieth-Century Dance.