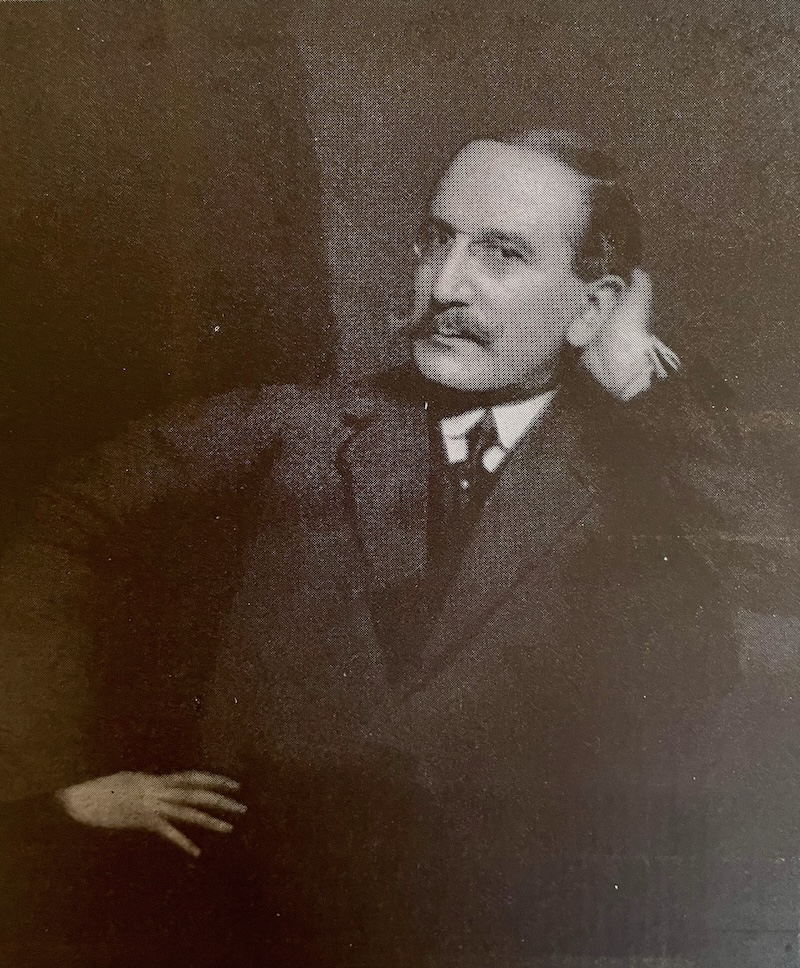

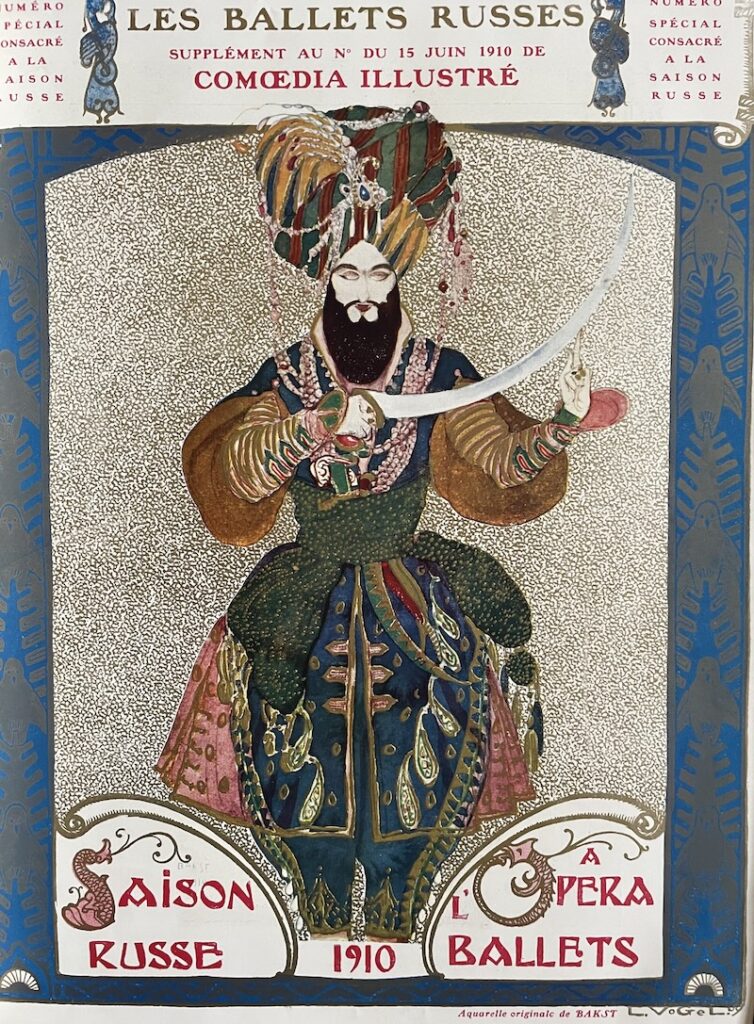

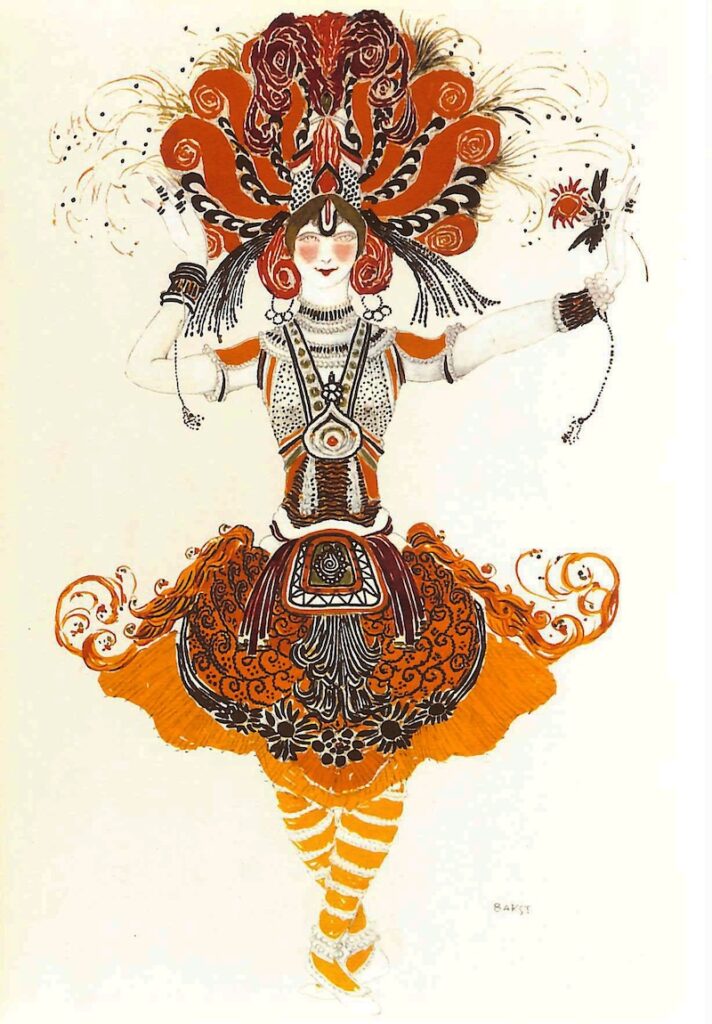

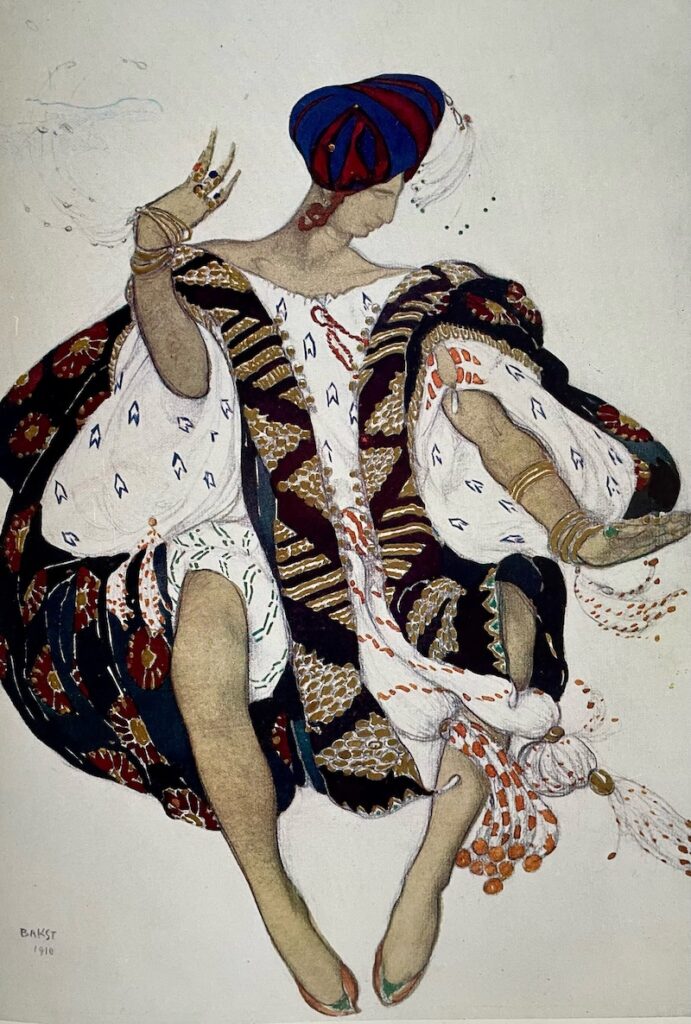

It’s hard to think of a stage designer who has made more of an impact on ballet than Léon Bakst, who died 100 years ago this December. His sensational sets and costumes for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, especially Schéhérazade, stunned audiences, and Bakst was also responsible for designing perhaps the most famous ballet costume ever – Anna Pavlova’s tutu for The Dying Swan. His work was alluring and enticing, and it continues to enthral today.

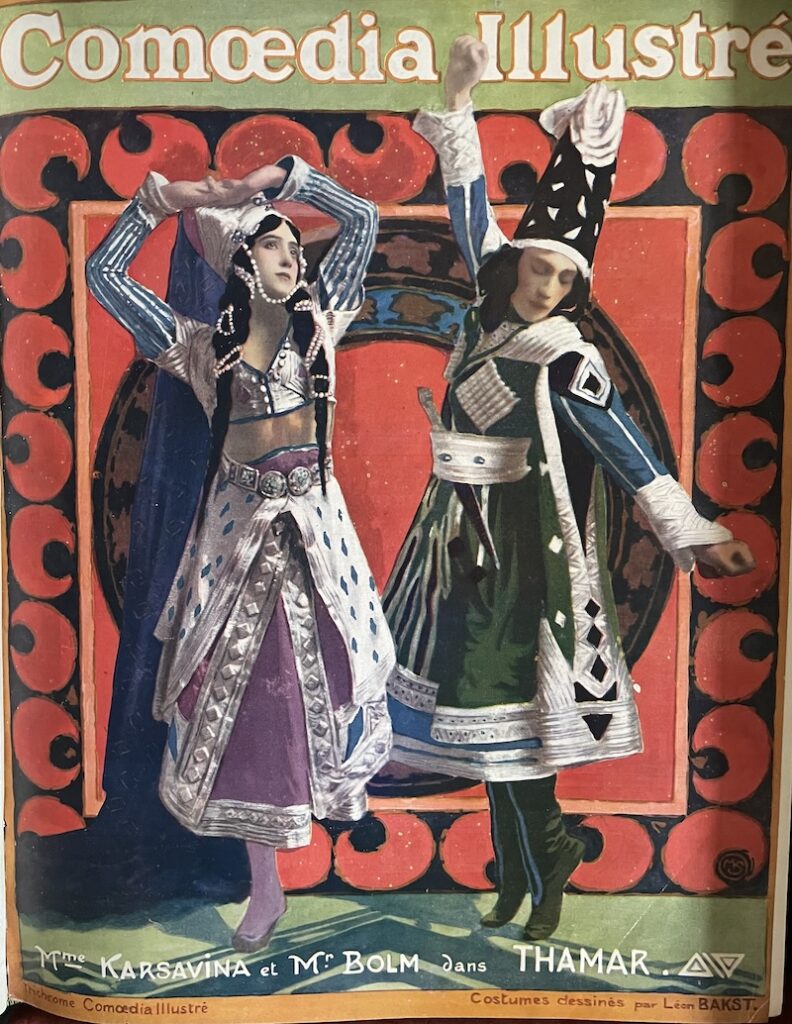

‘Bakst was the most audacious and imaginative colourist who ever worked for the stage,’ said Richard Buckle in the 1981 exhibition catalogue Spotlight. ‘He was exotic, fantastic,’ Tamara Karsavina wrote in her autobiography Theatre Street. ‘The spice and sombreness of the East, the serene aloofness of classical antiquity were his.’ Karsavina also remembered him as ‘a dandified young man in appearance, pernickety in his ways.’

Born in Russia in 1866 to a middle class Jewish family (his grandfather was a military tailor), Leyb-Khaim Rosenberg, as Bakst was originally named, studied at the St Petersburg Academy of Arts and later at the Académie Julien in Paris. An excellent draughtsman, he initially worked as an illustrator and portraitist, and during the 1890s became involved with a circle of artists and writers, including Alexandre Benois and Serge Diaghilev, who went on to found the influential World of Art (Mir Iskusstva) magazine. The group held strong views on everything – music, theatre, art, design and literature – and helped launch what became the Ballets Russes.

‘Bakst designed perhaps the most famous ballet costume ever – Anna Pavlova’s for The Dying Swan’

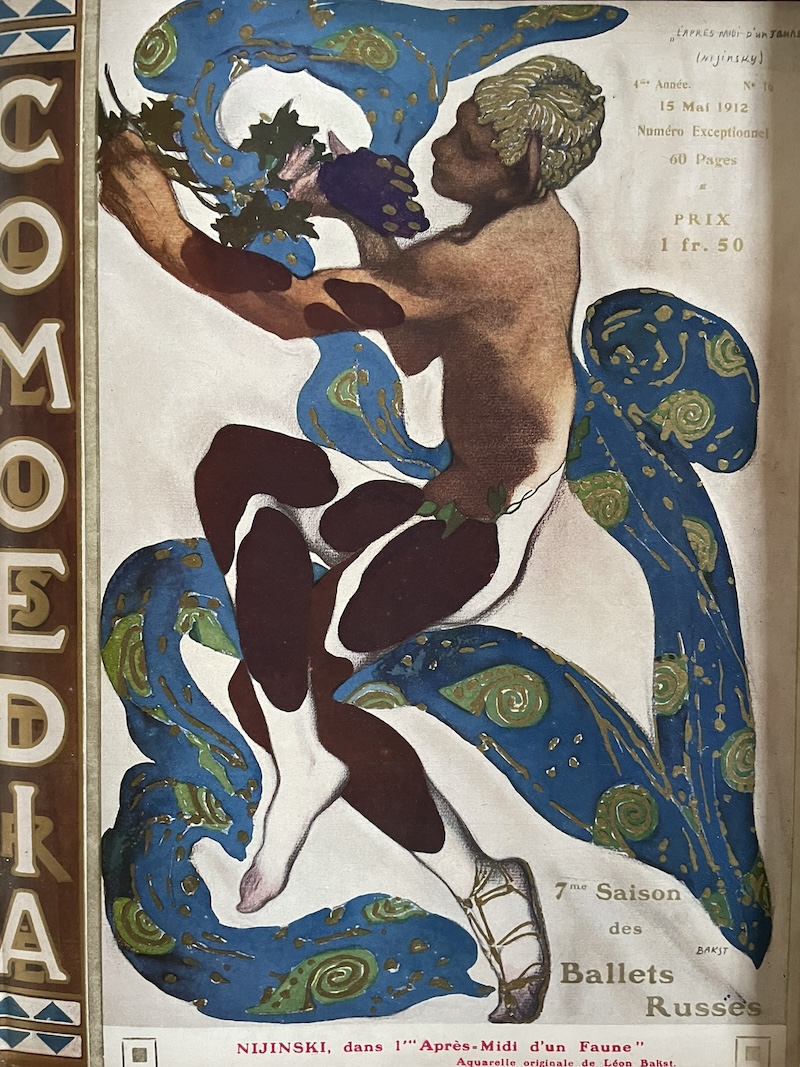

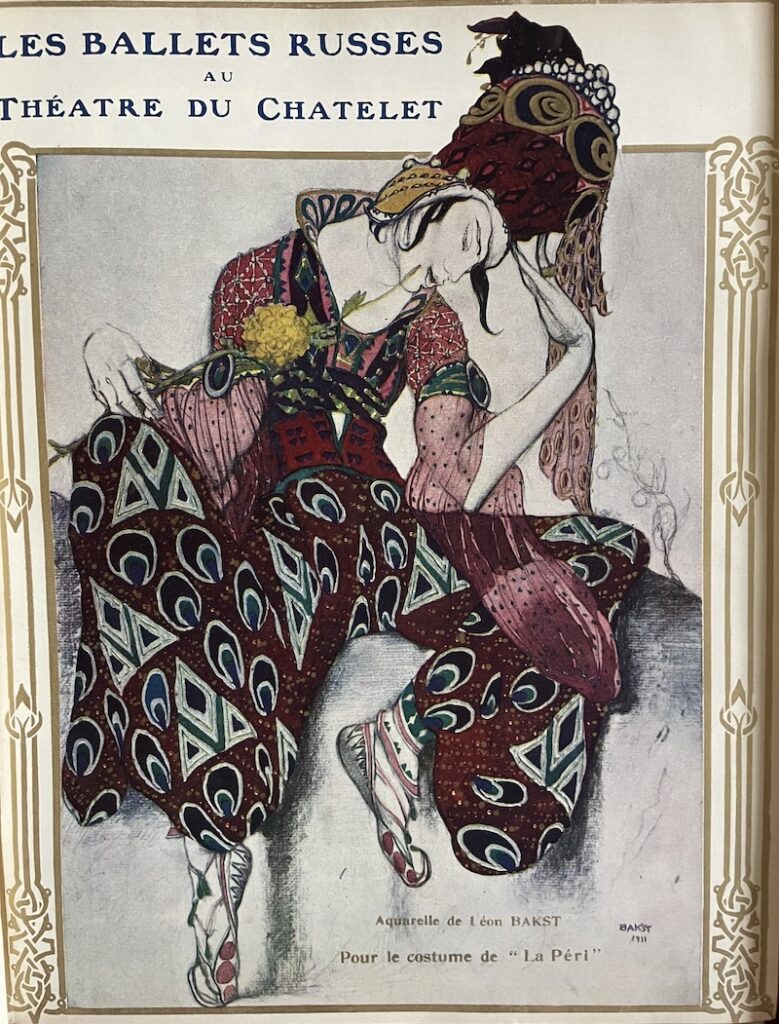

Rejecting the ossified repertoire of the Imperial Ballet, in 1909 Diaghilev gathered some of the greatest talents in dance, choreography, music and design for a series of spectacular seasons in western Europe that took audiences by storm. The public thrilled to the dancing of Vaslav Nijinsky and Karsavina, the choreography of Mikhail Fokine, the music of Igor Stravinsky, and designs by Bakst and Benois. Something new, exciting and unashamedly erotic was unleashed in ballet, and people responded especially to the vibrant, outlandish and intoxicating sets and costumes.

Where did Bakst acquire his unique sense of colour? ‘It must have come from Russia’s orientalism, and also Bakst’s visits to Greece,’ considers Sarah Woodcock, a former curator at the Theatre Museum, and an expert on the Ballets Russes. ‘The colours in ancient Greek sculptures, and the sense of light made a huge impact on him. It was like opening a door to light and colour, which was reflected in the music and choreography of the Ballets Russes. Bakst hadn’t trained as a theatre designer, but he did the right thing for the right ballet.’

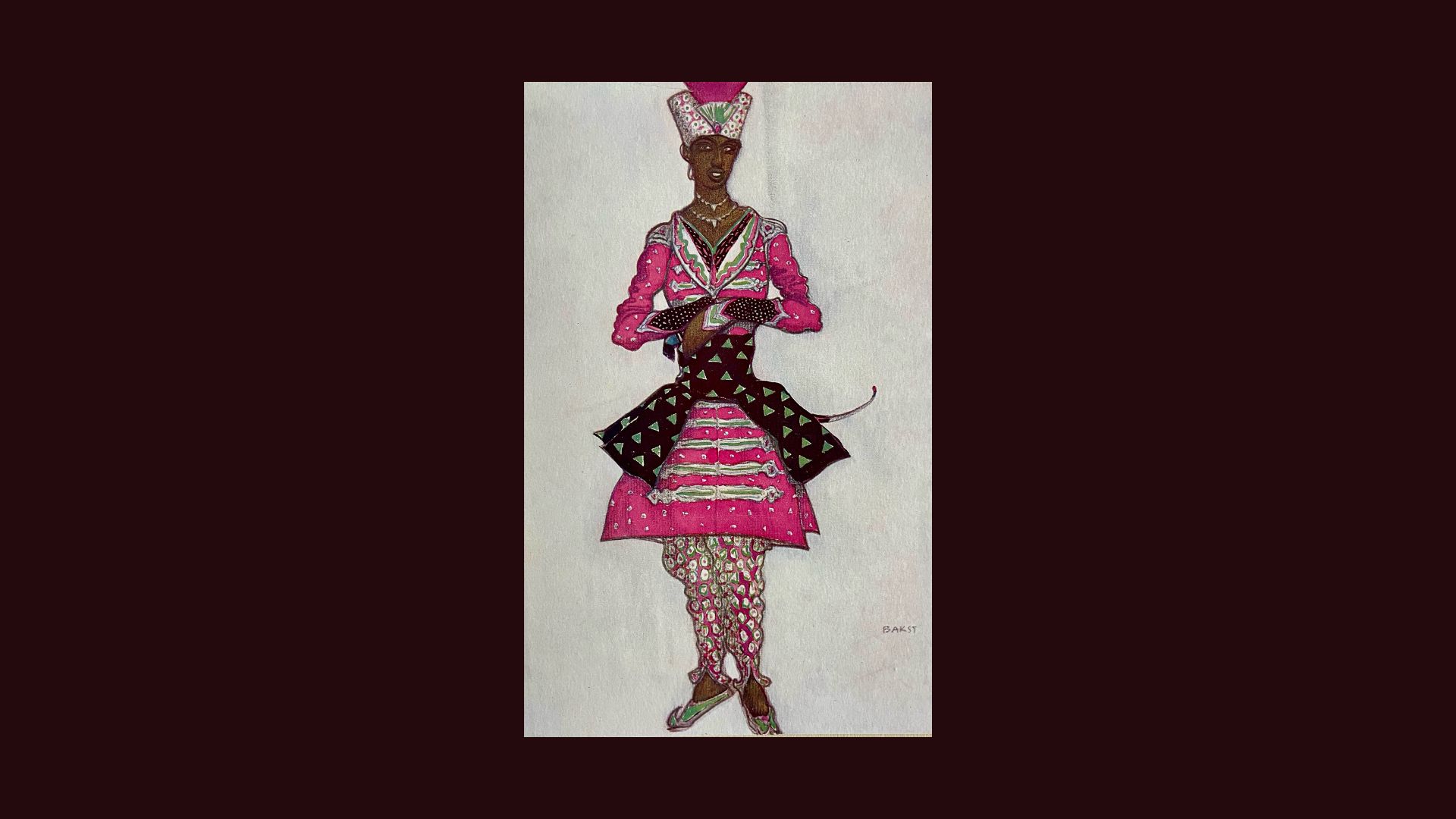

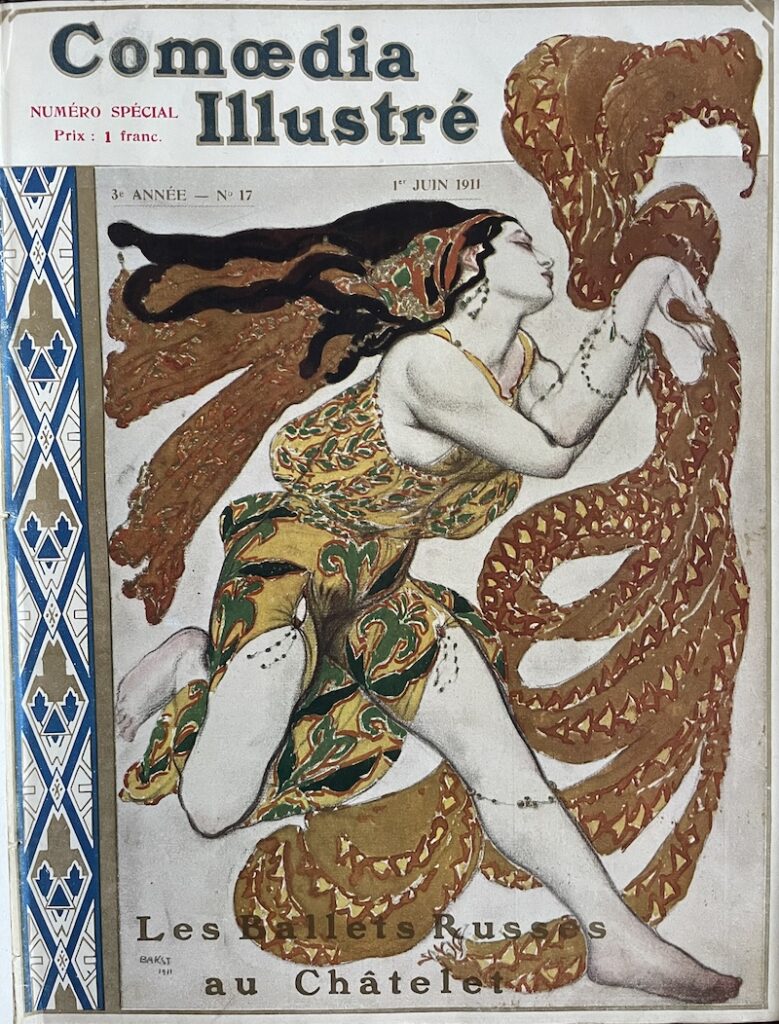

What was it about Schéhérazade, in particular, that was so sensational? Buckle notes that in 1910, ‘this scene of orgy and slaughter in the harem had unheard-of combinations of blue and green, of pink and red. Immense looped curtains and pendant lamps took the place of architecture.’ In Speaking of Diaghilev, a volume of interviews by John Drummond, ballerina Lydia Sokolova remembered, ‘Oh, it was a moment when the curtain went up, and you saw these vivid reds and blues and greens, and the Bakst thing came at you.’

‘It was partly the explosion of colour and patterns, and the mix of colours in his costumes and scenery that impressed audiences,’ agrees Woodcock. ‘In the Edwardian era people adhered to the colours of mourning, so were often dressed in shades of black or subdued colours. Bakst was like a huge explosion of colour, and his designs were very exotic.

‘Bakst was the right person at the right time with the right people’

Sarah Woodcock

‘He was brilliant in the way he matched his sets and costumes – in works like Thamar, the colours are amazing – and there was a total stage picture. Bakst’s productions were unlike anything people had seen before, and were the opposite of the gloom and minimalism of designers like Edward Gordon Craig. Bakst was the right person at the right time with the right people. His designs were all shaped by his sense of line and colour, and based on thorough research, but the mixing of colours takes a real eye to get it right.

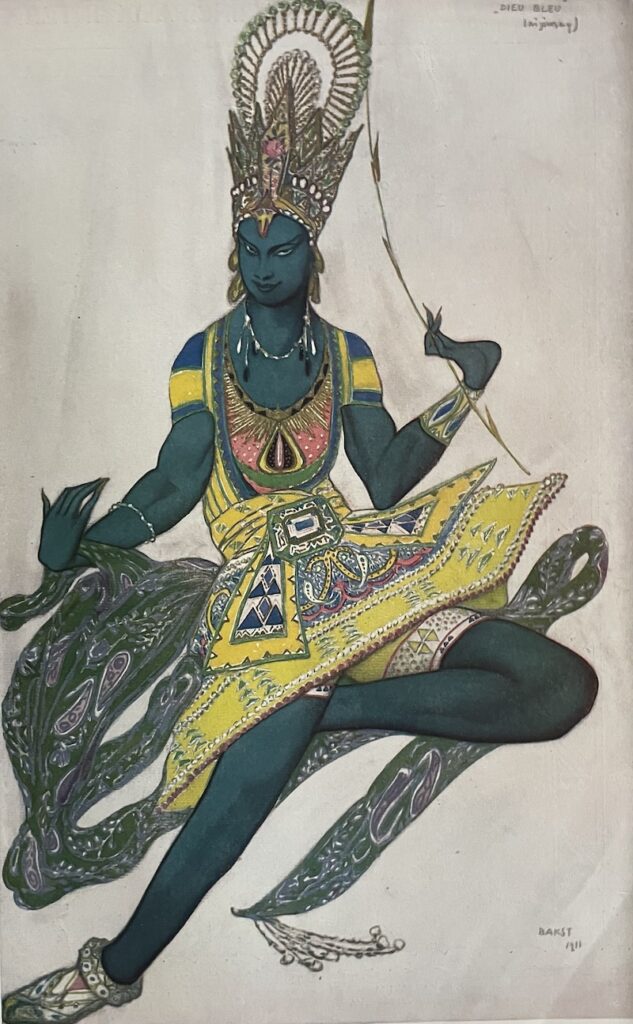

‘The realisation of his costumes was important, too, and he worked regularly with trusted people like Mme Muelle in Paris. The costumes that survive today are for ballets that failed, such as Daphnis and Chloë and Le Dieu Bleu. Karsavina’s bright blue costume for Zobeide in Schéhérazade [now in the Victoria and Albert Museum] is a remarkable survivor, as she must have worn it many times.’

His costumes were also highly erotic – though Woodcock adds that, ‘many of the [semi-nude] drawings attributed to Schéhérazade aren’t actually costume designs at all, and originally there wasn’t too much actual flesh seen on stage. The costumes were solidly made and often worn over stockings to give the appearance of naked skin.”

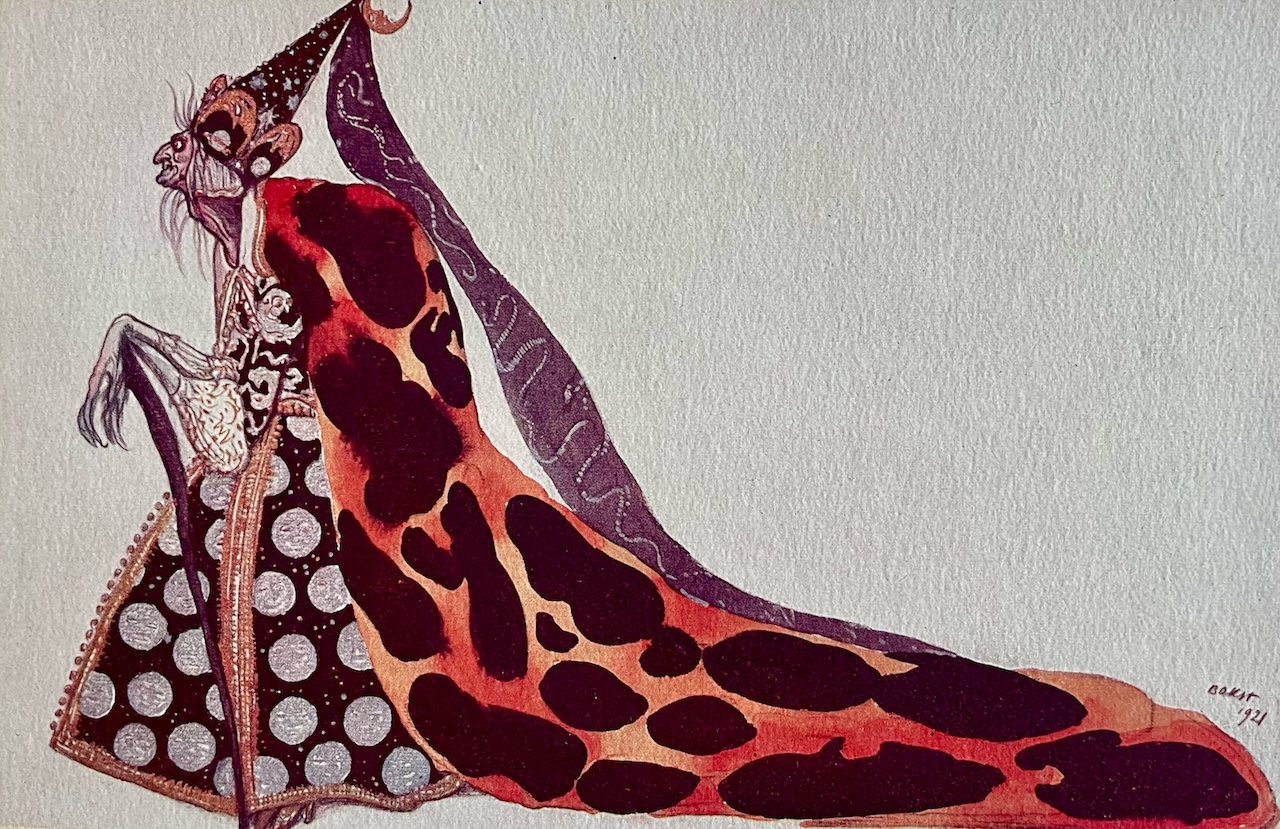

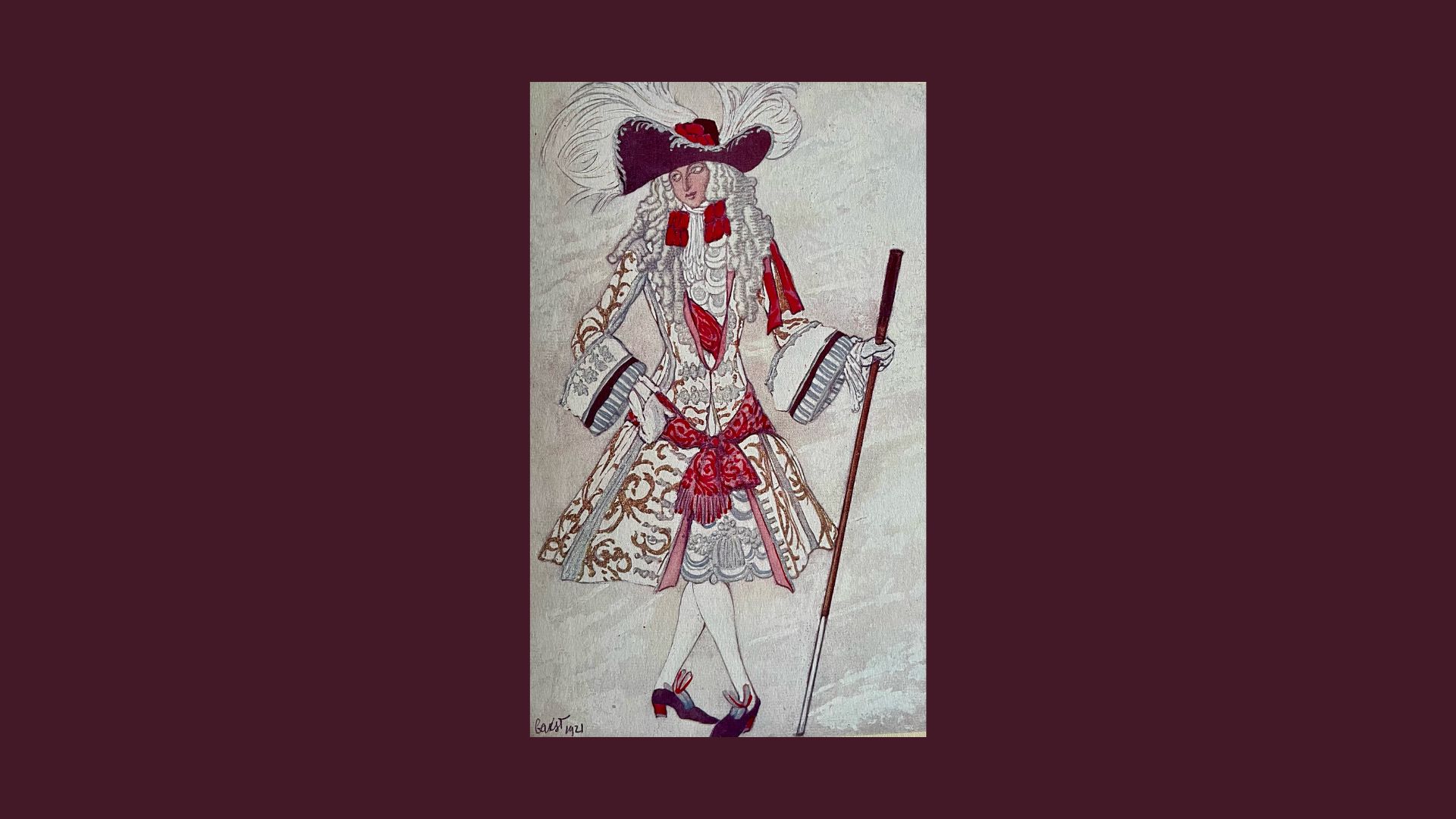

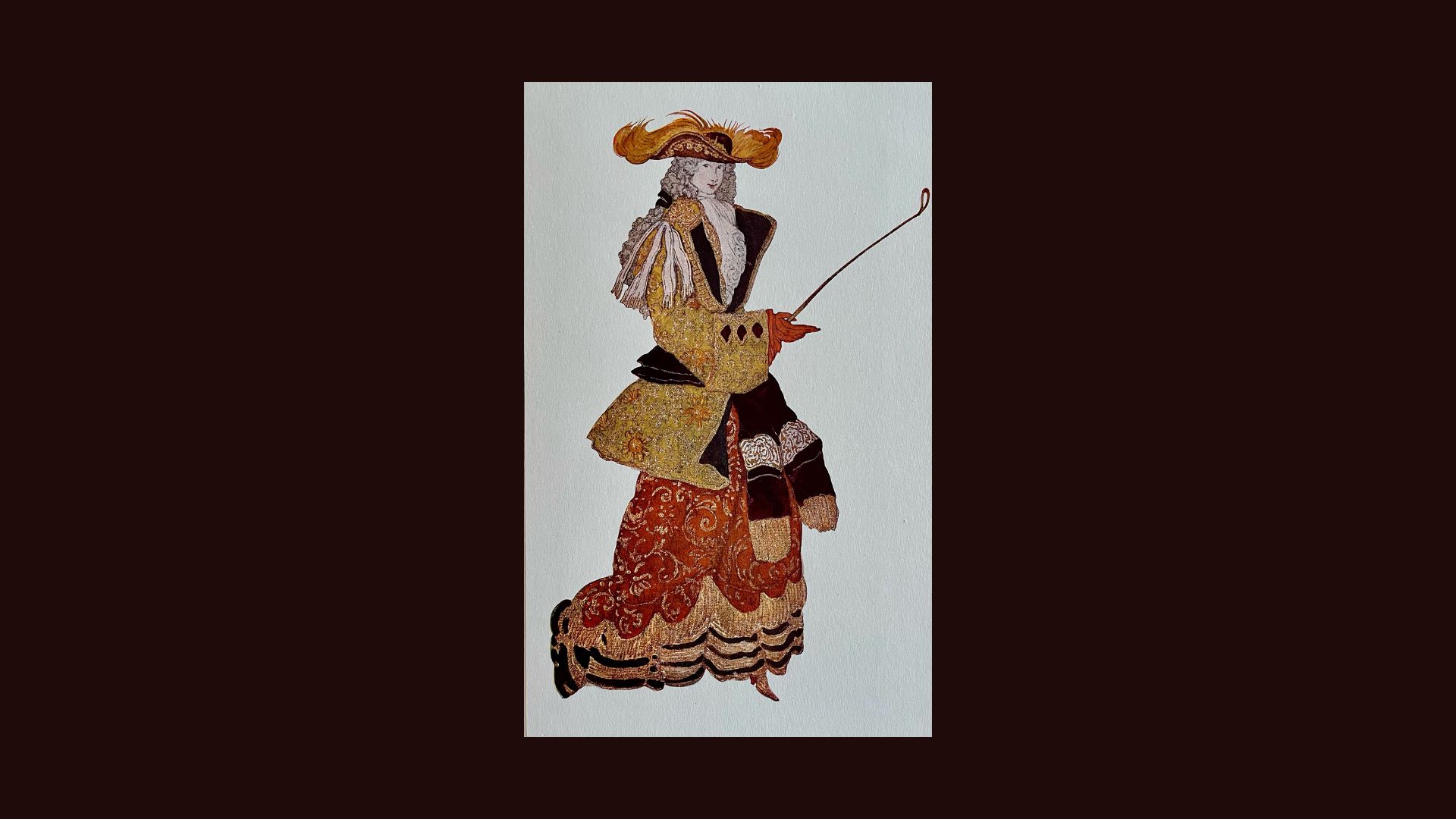

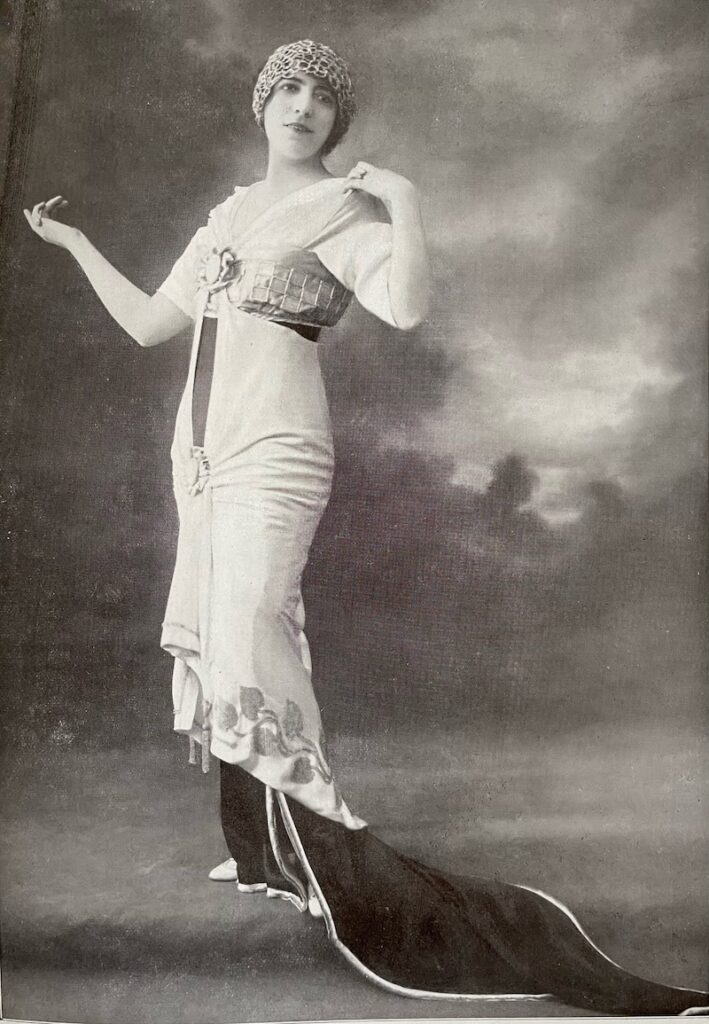

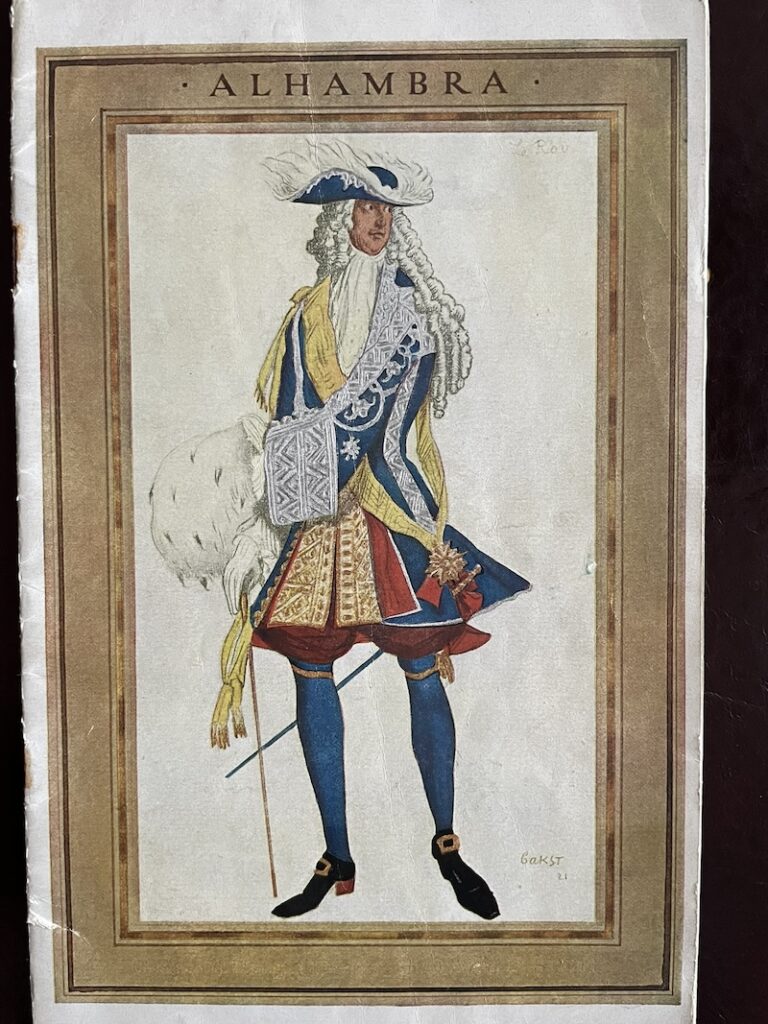

‘Bakst worked in a realistic style for ballets like Jeux in 1913,’ Woodcock continues, ‘where the costumes came from the couture house Paquin. In “historical” works, like The Sleeping Princess [as The Sleeping Beauty was known] and The Good-Humoured Ladies, he gave an overall feeling of the period instead of going into great detail, and his colours for the costumes were much brighter. Diaghilev did not have a strong classical company at the time of The Sleeping Princess in 1921, so it became as much a spectacle as a classical ballet.’

What was it like to appear in a production by Bakst? Karsavina recalls just before the premiere of Le Spectre de la rose, how important it was for Bakst to get every detail absolutely right. He exclaimed to Diaghilev: ‘You don’t understand, Serioja; we must give the atmosphere.’ In Dancing for Diaghilev, Sokolova remembers the first night of The Sleeping Princess, wearing ‘the richest costumes the company had ever worn… To make an entrance into that scene by Bakst was really to be transported into fairyland. When the curtain went up one could hear the audience gasp. I would have given anything to have been in front and to have witnessed the effect as one gorgeous series of costumes succeeded another.’

‘When the curtain went up, one could hear the audience gasp.’

Lydia Sokolova

Bakst also had a far-reaching impact on both fashion and interior design. In The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow in 1911, Juliet Nicolson notes that, following the first performances by the Ballets Russes in London, the department store Harvey Nichols ‘cleared their windows of [the] white, cream and lilac of summer fashion and filled them instead with hangings in Bakst purple and red. In the bedrooms of Violet and Sonia Keppel, daughters of the old King’s mistress, divans were piled high with Bakst blue pillows, the walls covered in “eastern” murals. Leopard skins replaced carpets, light bulbs were dimmed.’ Bakst’s influence ‘revolutionised indoor decoration,’ agreed Leighton Lucas, also a Ballets Russes dancer. He told Drummond, ‘a friend of mine in Chelsea, she built a whole salon which looked like Schéhérazade, and she used to sit cross-legged with a turban on in Turkish trousers and smoke long cigarettes in a holder.’

Eventually, however, Bakst did go out of fashion. Woodcock says, ‘Diaghilev wanted to be at the forefront of things, and the First World War made a break for a lot of people involved with the Ballets Russes.’ Instead, Bakst worked with such extraordinary artists as Anna Pavlova and Ida Rubinstein, and created his famous Sleeping Beauty murals for James and Dorothy Rothschild (now on display at Waddesdon Manor).

A century on and Bakst’s designs still impress. ‘With the Ballets Russes, there was a wildness to it that made it exciting,’ considers theatre designer Richard Hudson. ‘To me, the most striking thing is Bakst’s opulence and use of colour, and also the amazing shapes to his costumes, especially in silhouette.’ Hudson gained a detailed knowledge of Bakst’s work when working on Alexei Ratmansky’s revival of The Sleeping Beauty in 2015. ‘Alexei was quite strict with me about sticking to everything as Bakst designed it. I went back to the source, but changed some of the colours – there didn’t seem to be a colour scheme for each act, which surprised me.’

‘There was a great feeling of people all working together at the Ballets Russes,’ concludes Woodcock, ‘and the ballets it performed became “whole” works rather than several disparate elements. That still holds today, when even surviving original costumes can make a huge impact. The Ballets Russes continues to have a cachet.’

Jonathan Gray was editor of Dancing Times from 2008 until 2022. He has also contributed to the Financial Times and Guardian, and is now a freelance dance writer.