One evening, when I was about seven or eight years old, my parents allowed me to stay up late to watch television. It was a special occasion, as ballet was rarely shown on TV then, and that night, performing in a gala on the BBC with Natalia Makarova in extracts from Don Quixote and Giselle, was a sensational new dancer. That man was Mikhail Baryshnikov, who had recently been making headlines because of his dramatic defection from the Soviet Union whilst on tour in Canada. He was a new star in the ballet firmament, and nearly 50 years later his name still causes a flurry of excitement whenever it is mentioned.

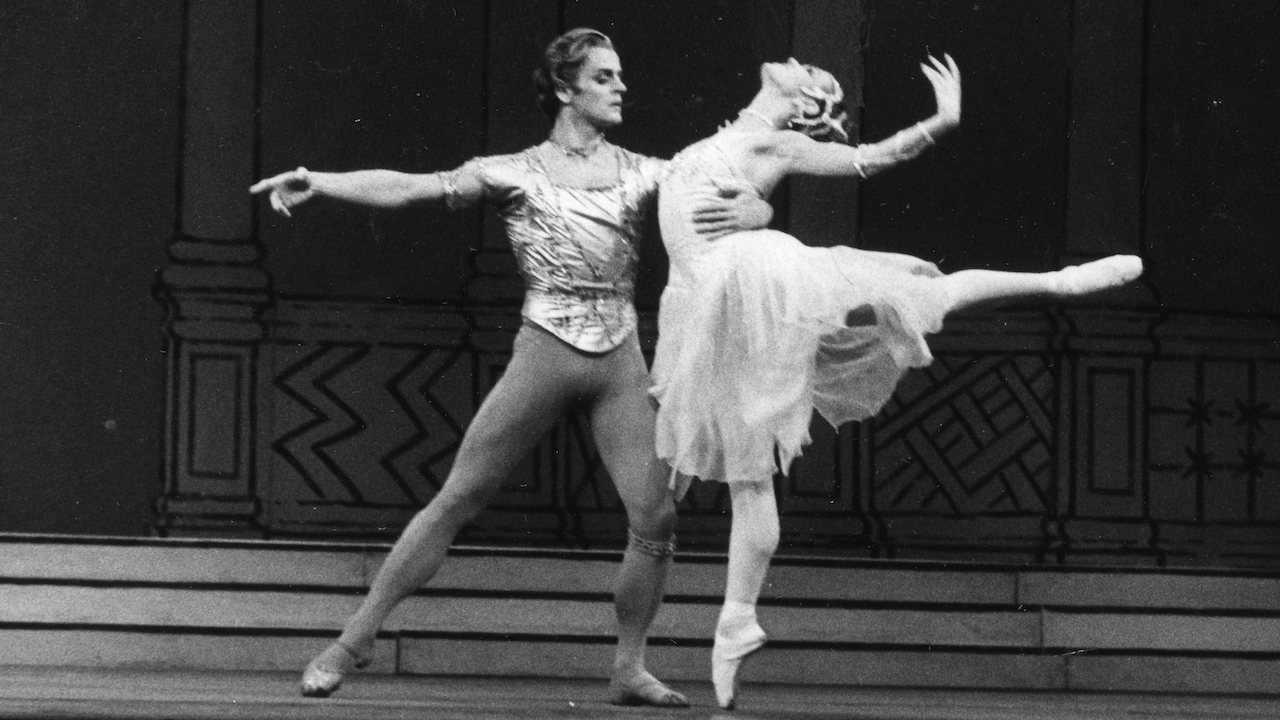

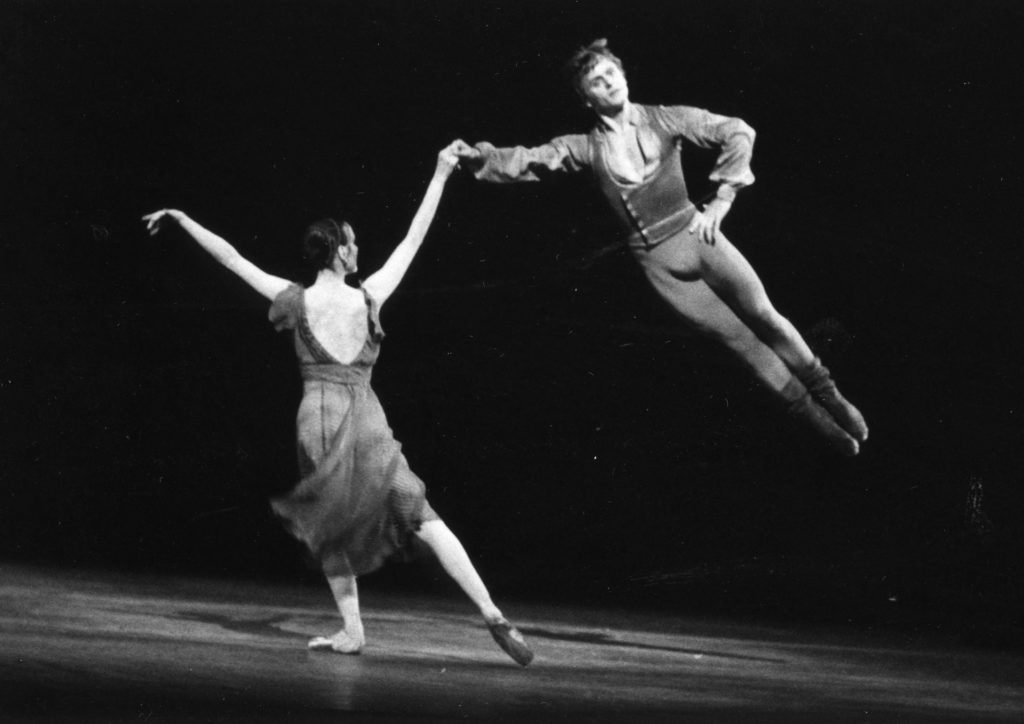

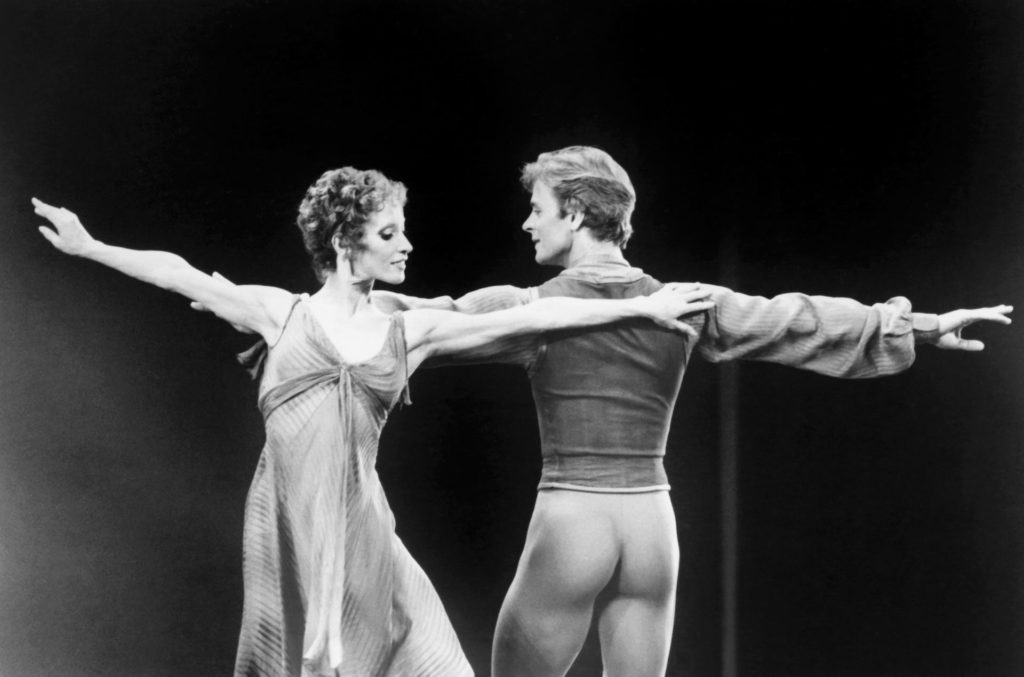

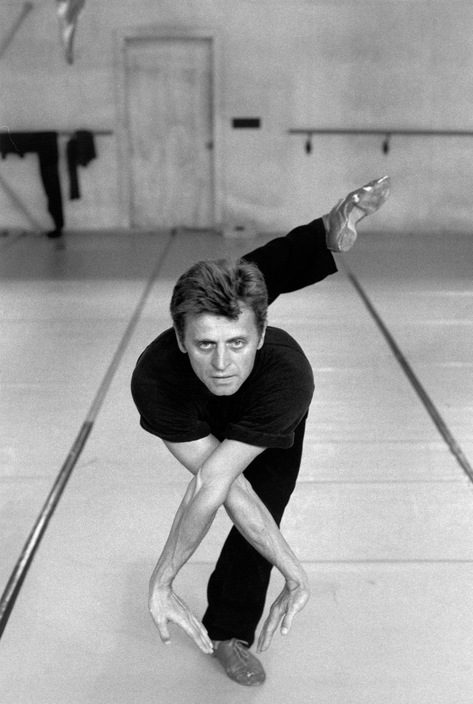

What was it that made Baryshnikov so special? Small, with blond hair and blue eyes, he was ‘a miracle of weightlessness who does the impossible with the nonchalance of a Fred Astaire,’ said Margot Fonteyn in The Magic of Dance. ‘He goes from extraordinary classical virtuosity to modern ballet as easily as a chameleon changes colour, and he expresses the sheer joy of dancing.’ In 1975, a year after Baryshnikov had defected, Mary Clarke, editor of Dancing Times, wrote of him in the Royal Ballet’s Romeo and Juliet, ‘What an artist! If I could use just one adjective to describe his dancing, I would choose “beautiful.”’

‘If I had just one adjective to describe his dancing, I would choose: beautiful’

Mary Clarke

Baryshnikov left Russia because he wanted to experience a more varied repertoire than was available with the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad, which he joined in 1967 and where he was continually typecast in such roles as Basilio in Don Quixote. Born in Riga in 1948 to a family with no connection to ballet, he became interested in dancing by chance after his mother took him to audition at the Riga Dance School. He was accepted at the school and took to dance immediately, but such was his facility for ballet that in 1964 Baryshnikov went to Leningrad to study at the Vaganova Academy. There, he joined the class of the famous teacher Alexander Pushkin, who had earlier nurtured Rudolf Nureyev and Yuri Soloviev.

Watching Baryshnikov in Pushkin’s class in 1965, friend and biographer Gennady Smakov recalled, ‘I immediately noticed a frail-looking, fair boy with distant, luminous eyes and sharp features. Not only the rare coordination of his pirouettes and jumps singled him out, but something special in the way he shaped every step – he was both impishly radiant and absolutely serious.’

‘Pushkin’s method also allowed the dancer’s individuality to take shape,’ Smakov continued. ‘A dancer fostered by Pushkin would suffuse movement with his own emotions… Misha’s jump was already strong, but Pushkin stimulated his natural coordination and so increased the jump’s amplitude and height.’ Indeed, watching Baryshnikov on film, when he dances he somehow seems to miraculously hover in the air at the very height of a jump.

‘It was, in fact, the perfection of his technique which constituted Baryshnikov’s individuality at the outset of his career,’ Smakov added. ‘His training had endowed him with absolute precision in… the Russian school… Despite Baryshnikov’s already extraordinary technique, few challenging roles were available to the young graduate at the beginning of his career. The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle and Swan Lake were still considered out of the question. Misha was given roles which often fell short of fully exploiting his gifts.’

In 1969, Baryshnikov won the Moscow International Ballet Competition, and in 1970 made his first appearance in the west. In a review in the Sunday Times, Richard Buckle noted, ‘London has taken Mikhail Baryshnikov to its heart, but on Friday, when he danced the Don Quixote pas de deux with [Gabriela] Komleva, there was a particular feeling of coronation in the air, as if he were being formally acclaimed as the great dancer of our day, which indeed he is… Here is the ultimate glory of the classical Leningrad school.’

‘It is necessary to try everything in dance. I should be able to dance anything’

Mikhail Baryshnikov

Following his defection, Baryshnikov was in huge demand. Making New York his home, he appeared regularly with American Ballet Theatre (ABT), and danced the great classics as well as a huge variety of roles by many different choreographers, including Frederick Ashton, George Balanchine, Mikhail Fokine, Kenneth MacMillan, John Neumeier, Roland Petit, Jerome Robbins, Glen Tetley and Antony Tudor.

One of his greatest triumphs at ABT was in Twyla Tharp’s Push Comes to Shove in 1976. At the time, Tharp, pre-eminent in the contemporary dance world, was a daring choice of choreographer for a ballet company, but in Push, according to Mary Clarke in Dancing Times, she created ‘a company work that mixed up classical, pop, every kind of dancing, and taught Baryshnikov to dance entirely in the Tharp manner.’

Baryshnikov told Walter Terry in Great Male Dancers of the Ballet, ‘I never did modern or jazz [dance] before now. It is fascinating and exciting! I had only had classical, so it required a different physical and mental preparation. It is important for me now to work in all styles possible. I could not be better than anyone else in Martha Graham’s style – I could not be a top dancer there, not the same as in classical dance where I have all the training. But the important thing is to be a dancer. And to be a better classical dancer, it is necessary to try everything in dance because you’ll come back to it better and stronger than before. I should be able to dance anything assigned to me, anything I want to do. That’s why I need this experience.’

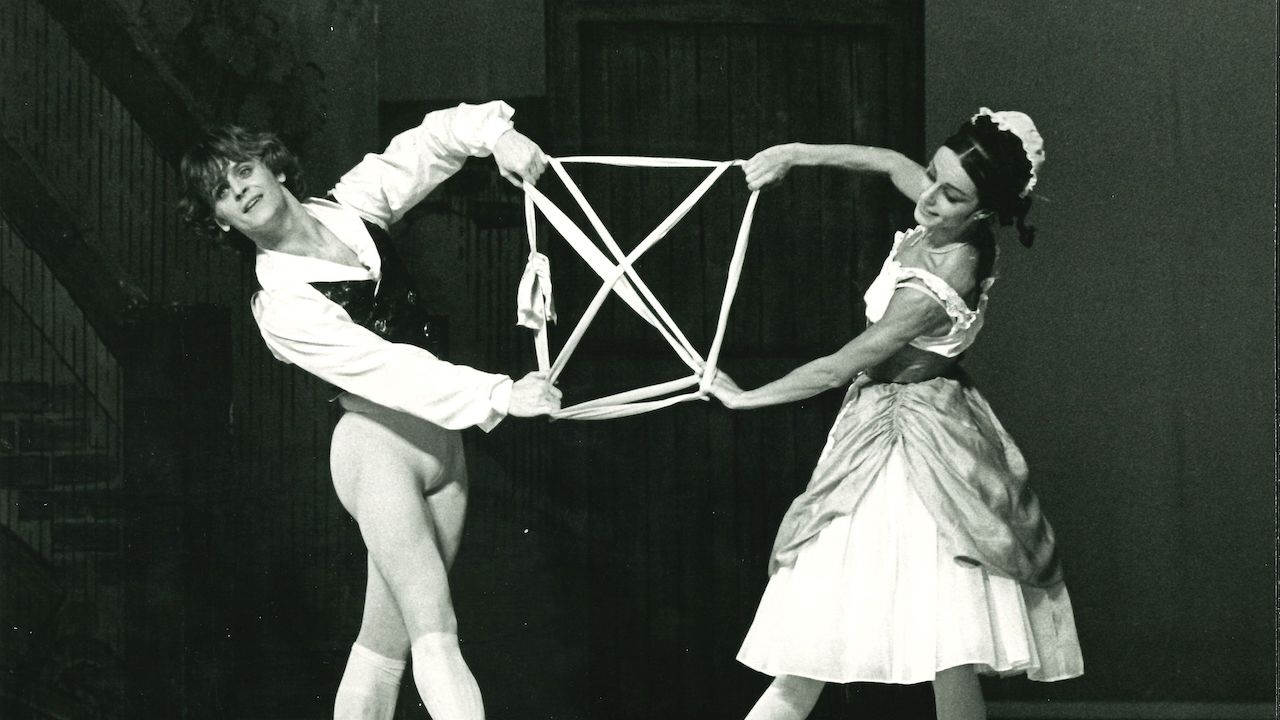

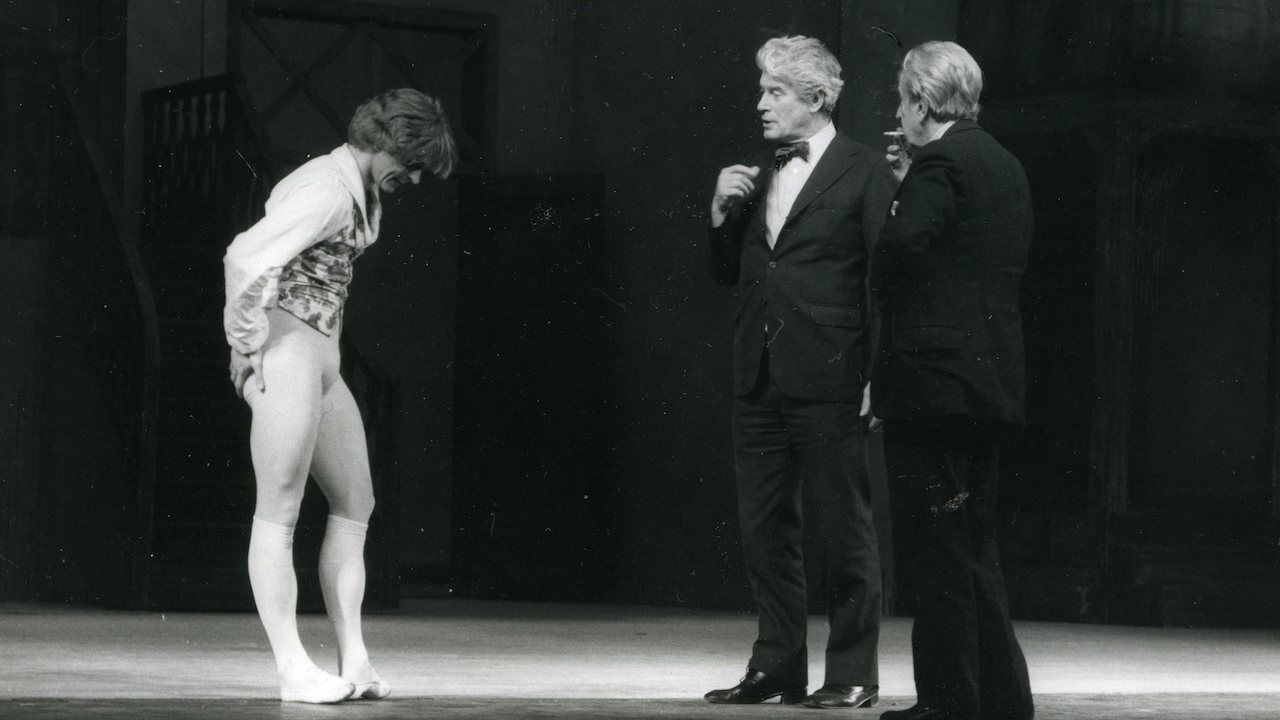

For Mary Clarke, another hit was Baryshnikov’s appearance as Colas in Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée with the Royal Ballet in 1977, in which he danced ‘the choreography as it is set, paying the greatest attention to Ashton’s subtleties of footwork. And how delicately, artistically, he completes a show of virtuosity. His very last grand pirouette was breathtaking in its speed and control but he ended quietly, with a perfect finish. Although Fille is the happiest of ballets… I found myself more than once weeping with pleasure in the beauty of Baryshnikov’s dancing. To have seen that performance, and to have seen him dance Spectre de la Rose with ABT in New York, is all I ask of male dancing.’ Clement Crisp added in the Financial Times, ‘Up in the air Baryshnikov enters an element in which, like a swimmer, he can disport himself. Dancing seems for him, as for how few others, the most completely natural method of expression.’ Later, in 1980, Ashton created Rhapsody on Baryshnikov, in which Julie Kavanagh, in her biography of the choreographer, described the dancer as a ‘shining golden bullet of energy.’

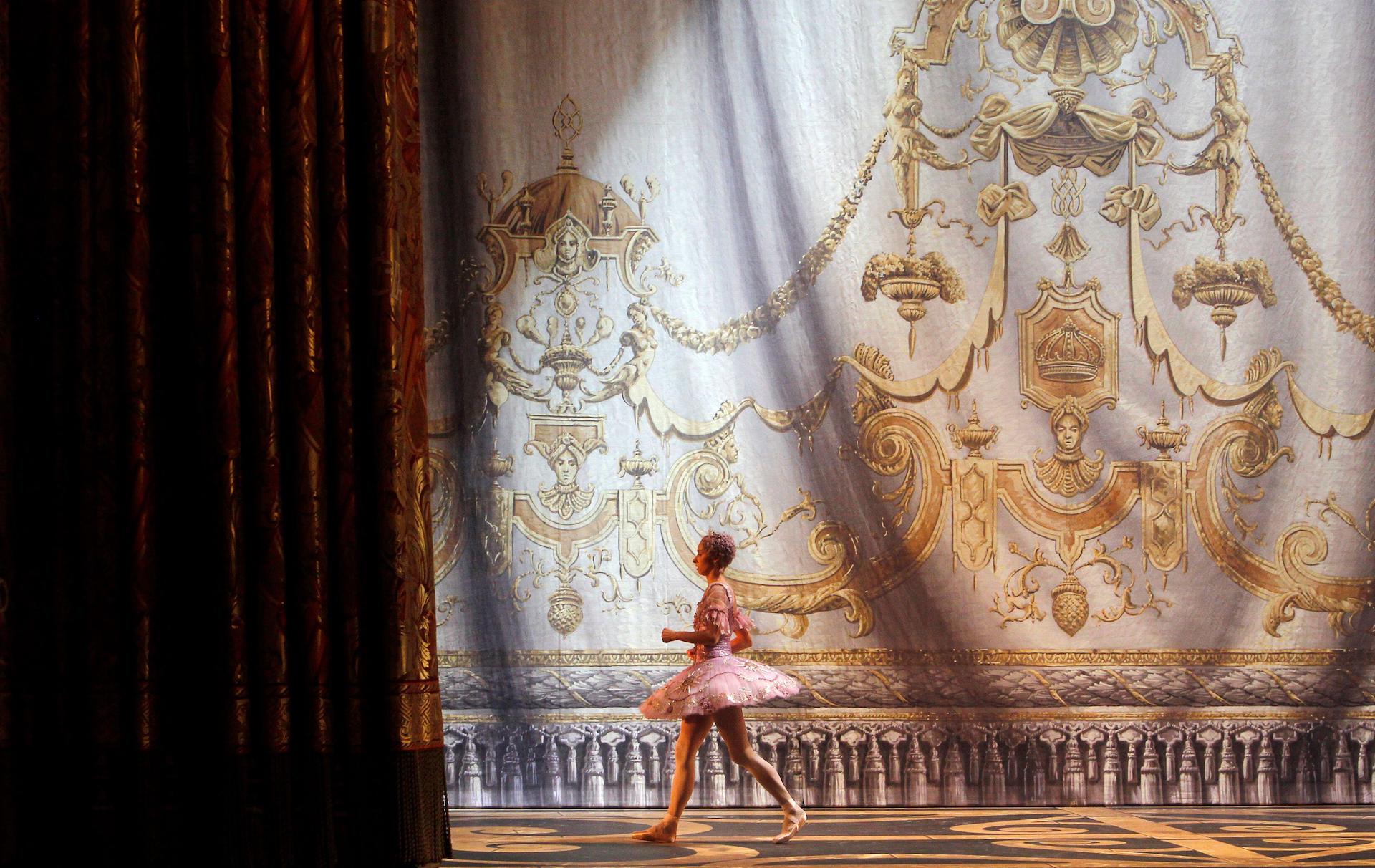

By the close of the 1970s, Baryshnikov had starred in the Hollywood ballet movie The Turning Point, appeared in a television spectacular alongside Liza Minnelli, created productions of The Nutcracker and Don Quixote for ABT and become a celebrity. An apparently unhappy season at New York City Ballet in 1978-79 followed (‘However disappointing the interlude may have been for Baryshnikov,’ Lynn Garafola noted wryly in her history of the company, ‘for NYCB it was box-office magic; for the first and only time in its history, sold-out houses became a common occurrence’), and he suffered his first knee injury that would eventually bring his classical dancing career to a close. Baryshnikov was appointed director of ABT in 1980, a position he held until 1989.

‘The ideal of movement is always realised in his art’

Clement Crisp

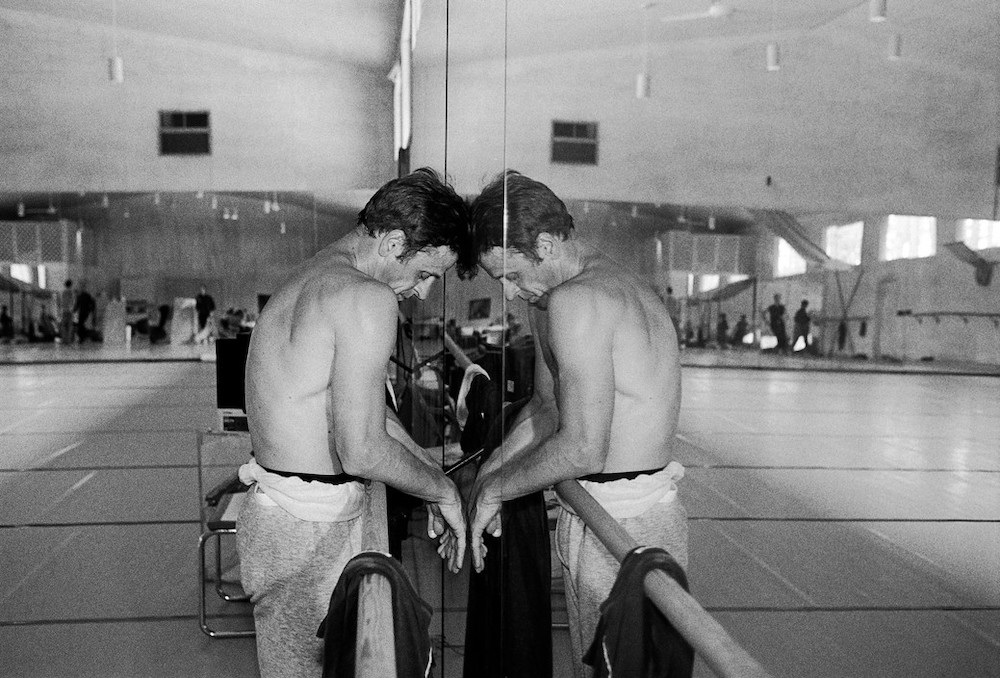

LOOK

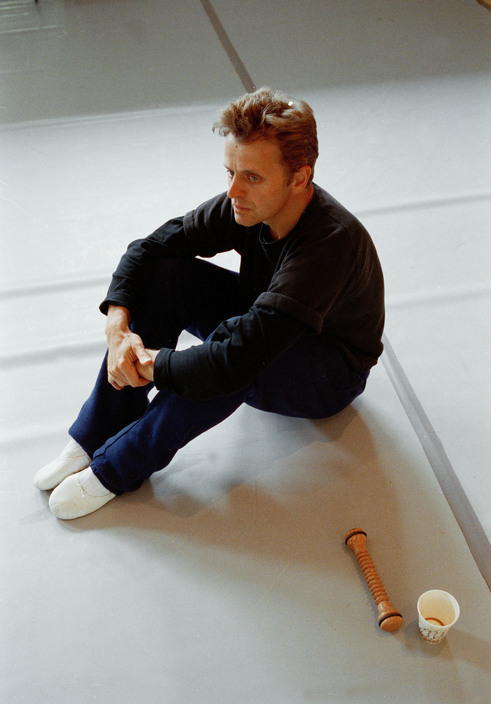

Thereafter, leaving ballet behind, Baryshnikov turned his attention towards contemporary dance. As Crisp noted when reviewing a 1993 performance in the Financial Times, ‘A distinguishing quality of Baryshnikov’s dancing has ever been its clarity. The classicist’s ideal of movement pure, sharply-drawn and impeccably shaped, is always realised in his art. This was what Leningrad training brought to a God-given physical instrument… We see dance as an essence, unalloyed and potent, set in long lines of beautiful and subtly-conceived activity. Baryshnikov now is, miraculously, Baryshnikov then.’

Watch

Baryshnikov dances Balanchine’s Apollo and Who Cares.

Jonathan Gray was editor of Dancing Times from 2008 until 2022.

He has also contributed to the Financial Times and Guardian, and is now a freelance dance writer.