‘My name is Imran, I am in jail for attempted murder.’

‘I’m John, serving a sentence for GHB.’

‘I am Peter, I’m 21 and serving six and a half years for robbery.’

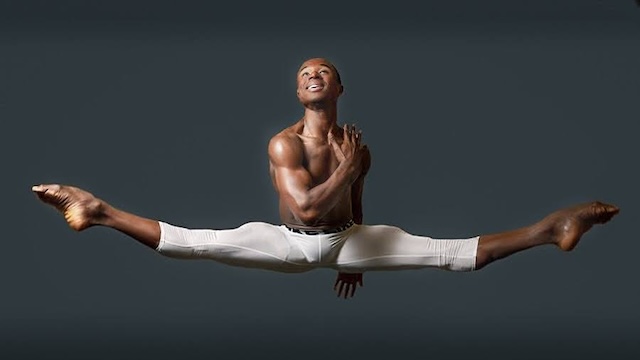

These young men are unlikely dancers who also happen to be prison inmates. They don’t exactly conjure up traditional images of would-be dancers, but thanks to the extraordinary work of some innovative companies, dance is part of their life behind bars.

I am a former custodial officer who worked with prisoners and I have a long-held interest in criminal justice. For Dance Gazette, I have spoken with an international mix of enlightened dance facilitators. The thing that unites everyone I spoke with is the desire to share their love of dance and movement to inspire and achieve positive change for people in prison.

Fallen Angels Dance Theatre is a company led by Paul Bayes Kitcher who inhabits an apparent dichotomy: he is a classically trained ballet dancer and a (drug) addict in recovery.

‘The darker the environment, the more impact you can have’

Paul Bayes Kitcher

The driving force of Bayes Kitcher’s work in prisons is to help inmates tell their own stories using contemporary dance and movement. He was at the height of his career, as a soloist with Birmingham Royal Ballet, when drug addiction took hold. Even after evenings out with ram-raiders who were trying to escape the police’s attention, he would still keep up with his performance timetable: ‘they used to drop me off at the stage door in a knock-off car, and I’d be going on to Swan Lake.’

After he stopped dancing and was in recovery Bayes Kitcher trained as a teacher on the RAD’s Professional Dancers’ Teaching Diploma, and set up Fallen Angels for people in recovery from addiction. In 2018, the company was invited into prisons to work with those serving time. Having some experience of struggling to engage with disaffected prisoners myself, I asked Bayes Kitcher what was key to his approach. ‘You need to be vulnerable in front of prisoners to engage them,’ he says. ‘They were initially hostile, but I started to tell them my story. So you just open up and start to build up their trust, and they realise that, basically, I’m one of them.’ Bayes Kitcher explains he is meeting people at the worst time of their lives. He encourages his dancers to turn ‘their pain into purpose’.

One such person is Richard (not his real name), a young man who worked with Fallen Angels. He was frequently in trouble for fighting but the movement sessions seemed to unlock a different side of his personality. ‘He had an amazing movement quality, was really focused and a leader,’ Bayes Kitcher says. Bursting with pride, he adds that on release Richard auditioned for Matthew Bourne’s production of Lord of the Flies and that he credits Fallen Angels for helping to start turning his life around.

Kevin Edward Turner is co-artistic director at Company Chameleon. He partnered with Odd Arts to deliver dance and movement sessions in prisons both in the UK and internationally. He tells me about their individual approach to working with prisoners in custodial settings combining dance, theatre and psychology to help inmates tell their own stories.

‘It’s about creating space for the participants to explore situations and scenarios that they might confront, and how they could find alternative pathways,’ he says. The aim over the sessions is for participants to develop their self esteem and value their creative choices. Turner explains, ‘this kind of work is incredibly restorative, and if we want people to move towards something more positive in their life, then we have to be able to equip them with the tools to be able to do that.’ He sees dance in prison as central to this process.

To some extent, this work is also personal to Turner. ‘I grew up in a working class community on a council estate,’ he says. He left home at 16 to go to dance school in Leeds, but explains that before dance school he could easily have got involved in the criminal activities he saw neighbours and friends fall into. ‘I could have been in prison,’ he says.

On the other side of the world, Lauren Bryne delivers the Royal New Zealand Ballet (RNZB) Prison Program. In 2017, RNZB started to offer workshops in prisons across the country. She tells me that despite its successes, there have been challenges along the way and that using the right language is important in attracting inmates to take part. ‘We used to advertise in the prison – come to ballet with the Royal New Zealand Ballet. You get a few people, but not as many if you say dance fitness,’ Byrne says.

‘A lot of men said dance opened up conversations with their daughter or partners’

Lauren Byrne

Keen to reach as many people as possible, New Zealand’s leading ballet company needed to adjust their offering: ‘80% of the time we are not teaching classical ballet, we are teaching dance in an accessible way to people who haven’t experienced it before.’ For those who attend Byrne’s sessions there are many potential benefits. ‘A lot of the men I have taught,’ she says, ‘have said how much it opened up the conversation with their daughter or partners, or others they have lost contact with because they have been in prison for so long.’ This is a resonant theme: Daughters, a recently released documentary on Netflix, explores four young girls preparing for a Daddy-Daughter dance as part of a fatherhood scheme at a US jail in Washington DC.

In Portugal, former lawyer turned artist and activist, Catarina Câmara is putting her legal training to good use. In collaboration with prison authorities she began devising a unique project for inmates to experience dance called CORPOEMCADEIA (with the Company Olga Roriz). Not one to shy away from a challenge, Câmara tells me how she came to be working in prisons after 20 years as a dancer.

‘Some people don’t have a good relationship with words – movement creates a freedom to talk about themselves’

Catarina Câmara

‘After training in Gestalt therapy, I asked myself: where am I going to work? What kind of community?,’ she explains. ‘I said to myself: in the community that has no dance at all, where movement does not exist and is run like the military.’ Câmara describes wanting to work with male inmates who disguise any signs of vulnerability. Her work in prison has been focussed largely on a group that seems to be overrepresented in Portugal’s prisoner population: young men of colour who have African heritage.

For working in prison she develops two types of classes: one purely artistic, the other focused on practicing for freedom. ‘Practicing for freedom is where dancers bring what is happening [in their lives] when we dance, so that they work with this material as if it was in therapy, but through movement exercises.’ Improvised and dancer-led, it allows people to tell their own stories.

I wonder what dance offers inmates that other forms of expression cannot? In response, Câmara highlights the democratic nature of dance as an art form. ‘Some of these people don’t have a very good relationship with words, because they were not finely educated, but they also have beautiful things to teach. Movement creates a language, ability and freedom to talk about themselves, without being stuck in the written form.’ She also has plans to incorporate trainee lawyers into her programme, to increase mutual understanding between inmates and lawyers.

It would seem that dance has an extraordinary ability to connect, inspire and help people to escape even these most challenging circumstances. Bayes Kitcher of Fallen Angels has a final observation about the rewards of this work in prisons: ‘the darker the environment, the more impact you can have.’

Some names have been changed to protect identities.

Watch

A trailer for the documentary Dancing with Câmara

Charlotte Rowles is a broadcaster and producer with a special interest in criminal justice.