Russia is turning inward. Isolation is a noble moral stance for President Vladimir Putin, especially from the west, whose nefarious influence is imagined to have forced Russia to invade Ukraine. The west no longer respects traditional values, according to Putin, and so Russia alone defends marriage and conservative principles.

Since politics have always influenced art in Russia, the nation’s great cultural institutions, which receive the bulk of their funding from the government, have also been expected to turn inward and promote official ideology. The reality is much more complicated, especially in the intrigue-filled world of Russian ballet. Strange as it might seem, the Bolshoi Ballet has been one of the more progressive companies in the world.

Strange as it might seem, the Bolshoi Ballet was one of the world’s more progressive companies

The general director, Vladimir Urin, is a canny operator able to sense official policy without being instructed in it. He initially came out against the Russian invasion of Ukraine but has since, out of self-preservation, fallen in line with the Kremlin. Thus ended a period when he had effectively manipulated officialdom to his theatre’s advantage, balancing the past and the present by assigning ballets and operas based on Chekhov, Lermontov, Shakespeare and Woolf to iconoclastic directors and up-and-coming composers and choreographers. The Bolshoi at once respected and resisted tradition, challenging the Putin regime’s conservative cultural politics in defence of European humanist values. The Mariinsky in St Petersburg did nothing of the sort, tacking in the opposite direction under Putin loyalist Valery Gergiev.

Before the invasion, the Bolshoi’s offerings included experimental productions by Dmitri Tcherniakov, who staged a version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Sadko that playfully jabbed at the Bolshoi’s history and traditions and angered conservative critics for its ‘lies’ and ‘inauthenticity.’ Urin brought in David Alden to direct Britten’s Billy Budd with an international cast that included the Ukrainian baritone Iurii Samoilov in the title role. The Bolshoi has been open to Indigenous works (the Yakut opera Nyurgun Bootur, for example) and to performers with disabilities: a group of Russian wheelchair dancers joined the corps de ballet for A Hero of Our Time (2015), directed by Kirill Serebrennikov and choreographed by Yuri Possokhov. These same artists challenged LGBTQ+ strictures with Nureyev, which reached the Bolshoi’s stage in 2017 despite government efforts to make it go away. It’s hard to imagine such a provocative show being done in London or New York, even harder to imagine it happening again at the Bolshoi.

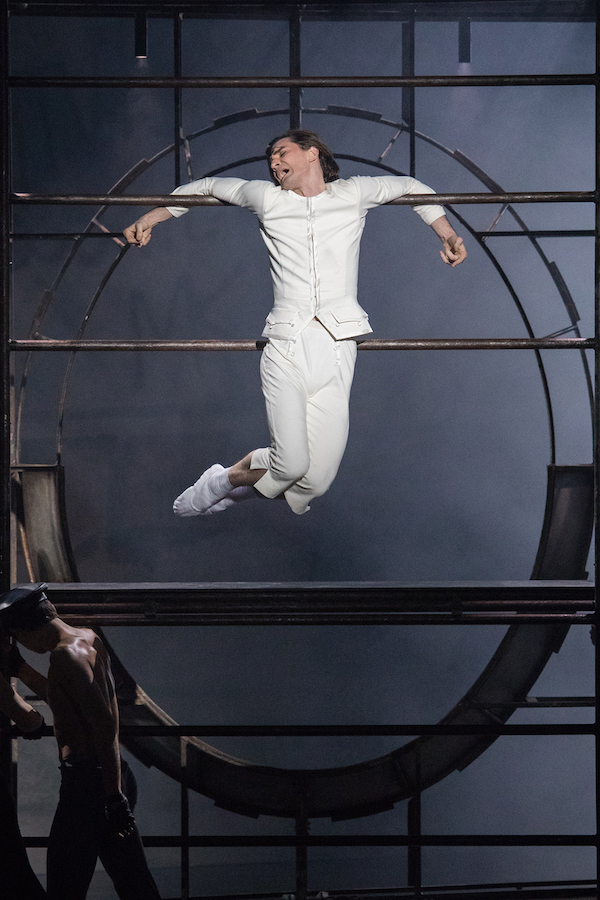

Nureyev tells the story of the dancer’s life in reverse, beginning with his death from Aids and ending in the Soviet Union. It includes a queer bacchanalia set in the Bois de Boulogne, the red-light district of Paris, after Nureyev’s defection to the west in 1961. Kitsch dialogues with camp; Nureyev’s life animates the clichés of Russian classical ballet. It is a study in contrasts, with an affirmation at its heart: just as you can’t choose your country, you can’t choose your sexuality.

The production was postponed just after the dress rehearsal in the summer of 2017. At a press conference in the theatre, Urin brusquely rejected the accusations that Nureyev had been cancelled by the Ministry of Culture. The ballet just wasn’t ready, he insisted. The artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, Makhar Vaziev, stood beside him in silence. In December, a modified version was premiered for a crowd of celebrities and politicians. Serebrennikov wasn’t there. He had been placed under house arrest, accused of looting the budget of a non-profit foundation that he had established under the previous Russian president, Dmitri Medvedev, to promote contemporary artists.

Among the Russian cognoscenti, the production’s greatest defender was Tatyana Kuznetsova, the dance writer for Kommersant newspaper and author of an unflattering book about the Bolshoi in the later Soviet years, when Yuri Grigorovich, now 96, was in charge of the ballet. The operative word in the Russian title is Khroniki, which means ‘chronicles,’ but can also refer to chronic illness and addictions. Mass forces are organised for mass entertainment in Grigorovich’s ballets, geared towards seemingly superhuman dancers of astonishing physical strength. They make use of folk dance but exclude character dance, a sin in Kuznetsova’s eyes. His inspiration came from Petipa and the streets, in the behaviour of people at bars, brothels, gyms and on battlefields. His works set forth proper lessons about good and evil, patriots and traitors, oppressors and liberators. Doing that meant simplifying – and impoverishing – balletic syntax.

The Bolshoi hasn’t returned to that era, but two of Grigorovich’s symphonic ballets are on the books this season: the exotic-erotic Legend of Love (1961), in which a queen sacrifices her beauty to save her sister and a hero sacrifices his love for the sister to save his people from water scarcity; and Ivan the Terrible (1975), denounced by Kuznetsova as a ‘hopelessly outdated’ jamboree of Russian and Soviet clichés that only tourists can love – except the tourists have largely disappeared. More interestingly, the Bolshoi premiered Vyacheslav Samodurov’s Dancemania, a high-octane battle of the sexes, in July 2022, and he’s spoken out against the invasion. Pierre Lacotte’s 2000 version of Pharaoh’s Daughter is still in the repertoire; he has said nothing.

Then there is the shameful case of Alexei Ratmansky, the former artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet and one of the most in-demand choreographers in the world. Having danced in Kyiv at the start of his illustrious career, he has repeatedly denounced the invasion and dramatically quit Moscow last February, leaving behind an almost-finished production of the ballet The Art of Fugue, stating that he doubts he’ll return while Putin is Russia’s president.

Despite his active support for Ukraine, he was not on the list of personae non grata dissidents until recently. A Russian colleague of mine explained that the Federal Security Service and pro-Putin cultural collaborators dislike ballet, don’t know foreign languages, didn’t monitor the choreographers much, and was probably unaware of Ratmansky’s comments made in English until an interview with the BBC and social media exchanges was trafficked around.

Now Ratmansky has been blacklisted and his name removed from his own ballets. On 13 November last year, he complained on Facebook that ‘The Bolshoi Theatre of Russia performed my production of Flames of Paris, two shows, afternoon and evening. My name as choreographer was erased. The same thing happened to all my other productions in Moscow: Giselle, Romeo and Juliet, and Le Corsaire. And at the Mariinsky Theatre all six of my ballets are now authorless according to their official website: Cinderella, Anna Karenina, Little Humpbacked Horse, Concerto DSCH, Seven Sonatas and Pierrot Lunaire have no choreographer.’ He wondered if the dancers noticed either the theft or the perversity of cheerfully dancing the work of a supposed ‘traitor.’ But no one has communicated with him from the Bolshoi.

The Bolshoi is stuck in a state of anxious limbo. Attitudes towards the invasion are mixed

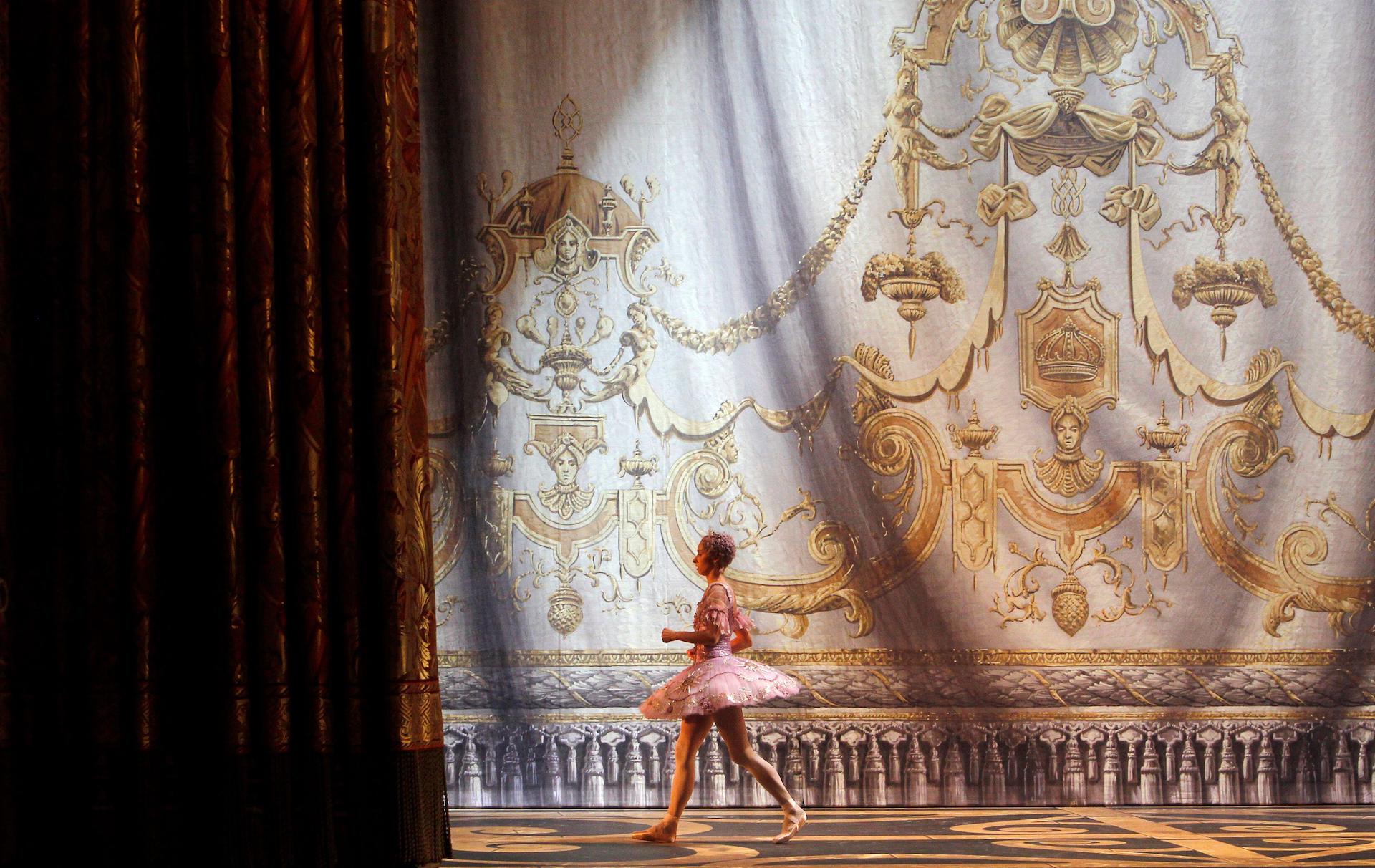

Like the Mariinsky, the Bolshoi is stuck in a state of anxious limbo. None of the dancers was mobilised in September; performers elsewhere have been sent to Ukraine. Attitudes towards the invasion are mixed: a small group of liberals in the theatre oppose it, yet some dancers with Ukrainian roots actually support it. In March, prima ballerina Olga Smirnova left the Bolshoi for the Dutch National Ballet, announcing her opposition to the invasion just beforehand. She’s missed by her colleagues, but they knew she was going to leave anyway.

The attitude in the company toward Putin’s actions mirrors that on the streets. Four-fifths of Russians are concerned about the fighting; the rest are indifferent while Kyiv sits in darkness. As I write this, the holidays are approaching in Moscow. Tickets to The Nutcracker sold out in a few hours.

Watch

Olga Smirnova explains why she left Russia and the Bolshoi

Mikhail Baryshnikov on Putin’s war

Simon Morrison writes about Russian music, ballet and Stevie Nicks. He is currently working on a history of Moscow.