What do you remember from your first major journey – from South Africa to train in England?

I came to England when I was 14. In those days people mostly came by boat, so we sailed from Cape Town. I lived in Johannesburg, 1000 miles away from the Cape, so we took a train: the first time I’d ever been on a train. Lots of friends and relatives had come to see us off, I saw so many people in tears. And I felt so guilty because I was jumping up and down for joy. I was just so excited by the prospect of coming to London.

The first big international trip you took with the Royal Ballet was to the USA in 1960?

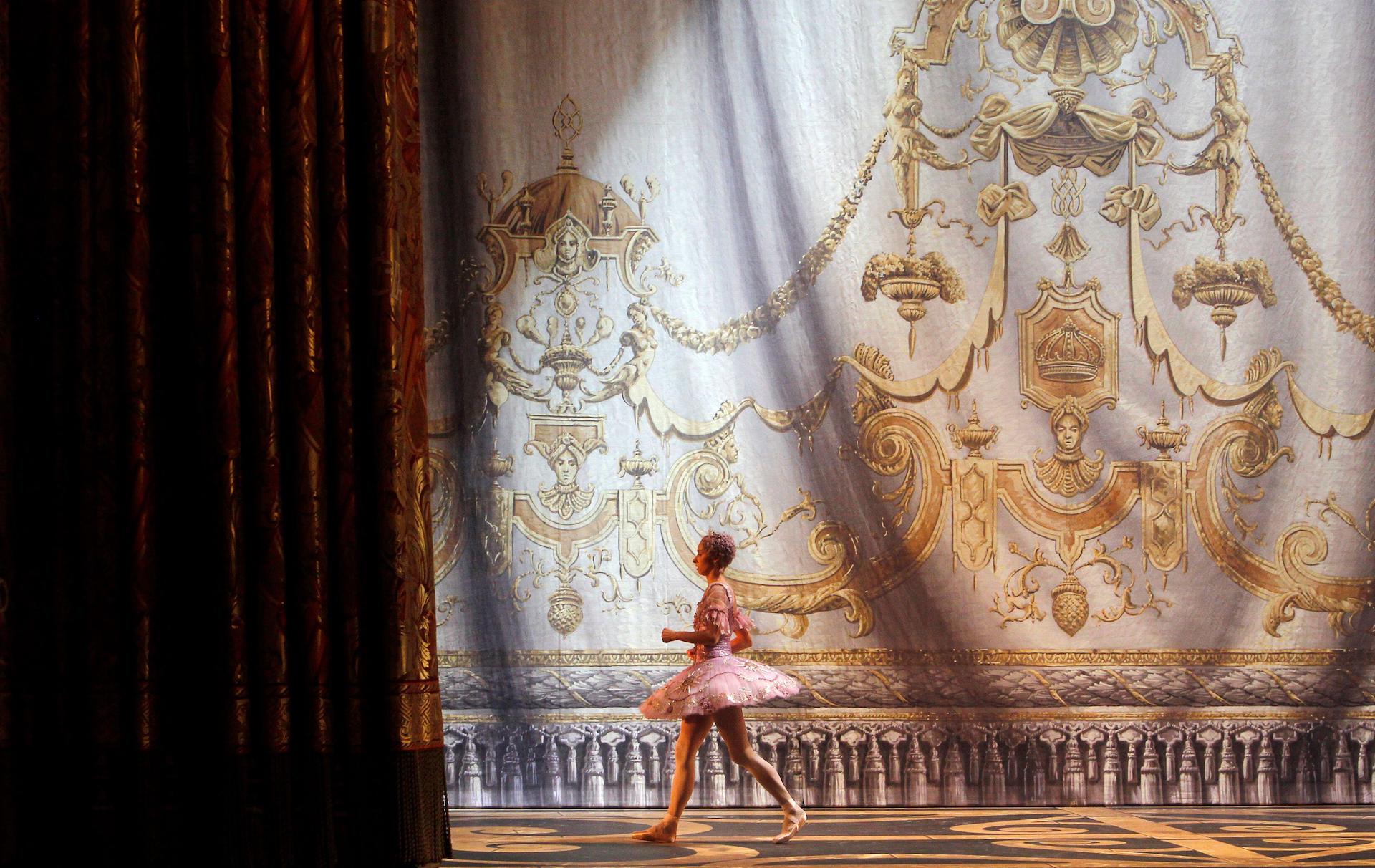

I turned 19 on the day we flew to America, and we did a five month tour of America. We started in New York for six weeks and then we went the length and breadth. There was a tremendous amount of one night stands – completely exhausting because you slept on the train and then had to get off at eight o’clock in the morning. We were expected to dress properly at all times: gloves and stockings with the seams straight up the back of the leg which we had to climb into in these little restrooms on the train.

What was it like to travel during through a still segregated America?

I was reminded of South Africa, because it was like apartheid. A member of the orchestra – a violinist, a lovely guy – was Black. And he wasn’t allowed to play in the orchestra in the south. He wasn’t allowed to travel on the buses or eat with us. I remember writing home to my mother and saying, this is like being in South Africa, it’s horrible. Through the 1960s, we went many times, and it got worse, really, because there were the assassinations of President Kennedy and Martin Luther King. There is nothing like travelling for opening your eyes. And at the same time, we were dancing our socks off, night after night.

How was your first trip to Russia in the 1960s?

It couldn’t have been a greater contrast. Everything was so regimented and people had told us that we would be followed at all times. We were told that we had to keep our opinions to ourselves, not even share them in the rooms, because everything would be bugged, even the bathroom. I remember having somebody who didn’t even hide the fact that he was tailing us. It was such a shock to discover that people lived like this, and that they had so little. But the audiences were absolutely amazing, people with such knowledge of the art form. While we were there, Rudolf Nureyev was defecting to the west in Paris, but not a drop of news got out. It was only when we came back that we discovered what had happened.

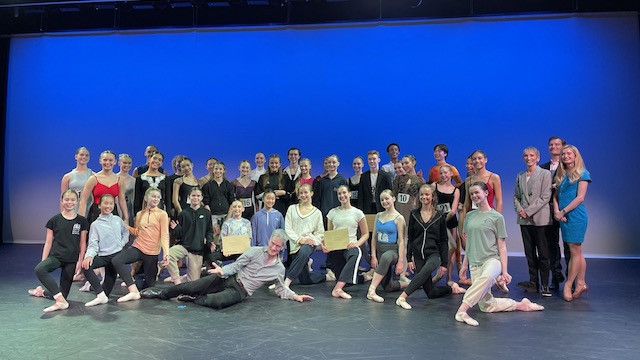

How did you persuade people to support the campaign for RAD’s new headquarters?

It was my belief in what the RAD gives the world – the importance of young people, understanding and appreciating dance, being well taught, being properly prepared for whatever their career will be. Dance influences them – the ability to communicate, to care deeply about something is so vital.

Why does dance matter to you?

The great thing about dance is that there is no language. It has taken us to so many places where you can’t really communicate with people: our first tour to Japan, to China, the first time we went to Russia, and then Brazil and Cuba. It’s been such a privilege to be a part of an art form that doesn’t need language. That’s been the great thing, taking it all around the world and discovering that people everywhere seem to understand.

Why Dance Matters

Why Dance Matters is the RAD’s podcast – a series of conversations with extraordinary people from the world of dance and beyond. We hope these insightful personal conversations – hosted by David Jays, editor of Dance Gazette – will delight and inspire you.