We are witnessing a re-energised fight against racial inequity and systemic racism. Since the brutal murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020 in the US, and through the Black Lives Matter (BLM) and Stand Up to Racism movements, many people have been emboldened to push for tangible change within their communities and industries.

In the UK, 100 current and former workers of colour at London’s Barbican arts centre banded together to share harrowing experiences of discrimination and racism in Barbican Stories, leading to a shake-up of staff, while a collective of theatre organisations recently launched an anti-racism rider to offer a practical toolkit for more racially equitable working conditions for touring shows and events.

It has been no different for dance industry leaders and practitioners who recognise this shift in momentum. In June, the TIRED Movement (Trying to Improve Racial Equality in Dance) and training organisations including the Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) came together to share racial equity practices. The usual buzzwords came up in the ‘Talking Dance: Improving Racial Equity’ symposium – diversity, inclusion, representation – yet the specificity of racial equity in dance teaching and how it affects young dancers sparked an interesting thread.

Karina H Maynard, a consultant, educator and panellist in the symposium, centres young voices in these conversations as ‘they are the stakeholders, they are the ones who are experiencing things.’ Maynard runs Continuing Professional Development programmes to improve racial representation in dance education and works with young people to strengthen their self-esteem. ‘I developed an approach of supporting young people [by] giving them spaces to explore identity, race, culture, [and] having conversations that are not normally had,’ she says. ‘[To] give them the opportunity to think about themselves as individuals and practice listening, so they get used to centring other people. I’m preparing an institution for an empowered, proud, young person.’

Are institutions ready for empowered

young dancers of colour?

Yet are institutions ready for empowered young dancers of colour? Dance organisations still maintain a rigid teacher-student hierarchy which, through many told experiences, stifles speaking out about racial or cultural needs. Speaking out isn’t easy when the environment is ill-equipped to deal with it.

For Seeta Patel, an award-winning Bharatanatyam and contemporary choreographer, meeting these needs can only begin when ‘the notion of change, of shaking things up, of being radical and trying to prioritise things differently isn’t seen as negative, disruptive or aggressive.’ These are labels easily placed on outspoken dancers of colour, who in turn are shunned, gaslighted and ignored for speaking out. The responsibility and accountability to create safer spaces lies at the top – from teachers to artistic directors – and this change needs to be led by those who are fully supportive of the process.

‘Part of your job, as someone who is trying to bring in more diversity, is to bring in the [people of colour] that scare you,’ Patel adds. ‘Bring in the ones that make you think “I am anxious about what this might be.” If that means you as an organisation conceding your current priorities, that’s the only way you’re really going to change.’

Racial equity in dance teaching should be treated as a safeguarding issue in Shannelle ‘Tali’ Fergus’ opinion. ‘I don’t know how often the people that are engaging teachers are in the room to see them teach,’ says the choreographer and agent for hip hop company ZooNation. ‘You’ve got to be in the space to see how they are with your students. Like an interview process for a job, I don’t think it would hurt to go through something like that.’

Fergus imagines a more robust screening process, focused on determining the potential for power abuse, racial discrimination, favouritism and bullying. ‘It absolutely should be on the list of things to look at,’ she continues. These initiatives may seem like box-ticking, she adds, but ‘as long as a young person has a teacher, mentor or someone with more experience to talk to, for them to feel validated in their feelings, that is still productive.’

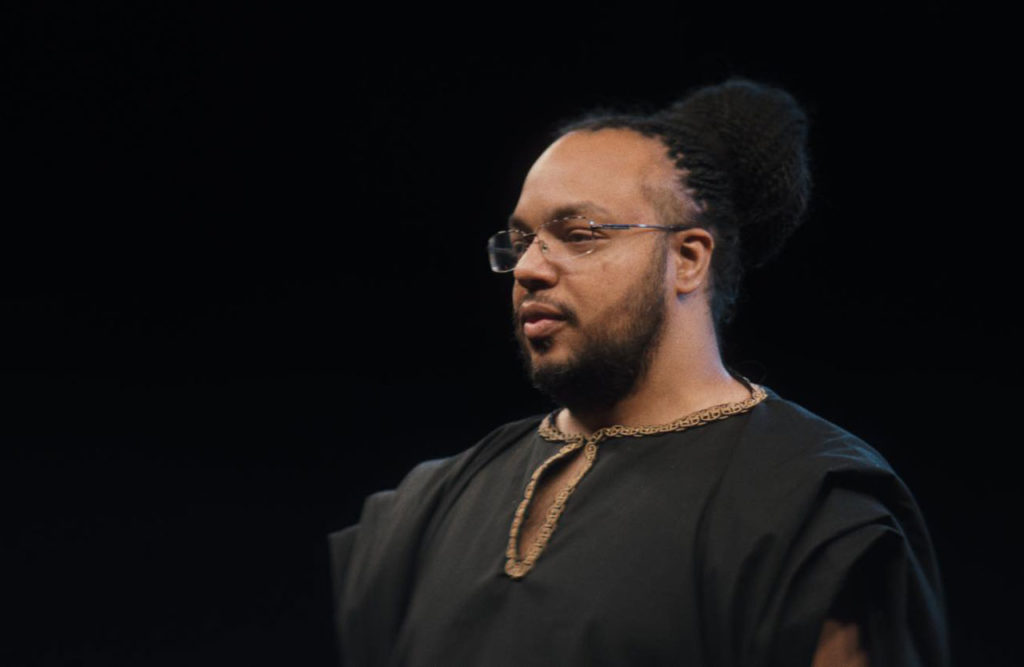

Thomas ‘Talawa’ Prestø, Artistic Director of Norwegian Tabanka Dance Ensemble, thinks we have to stop with ‘the right thing to do’ argument. ‘We keep wanting [organisations] to emotionally get it,’ he says. ‘It’s not about that. Real accountability is a need to be so professional that it doesn’t depend on whether an individual person truly understands what has happened or not.’

In Norway, schools are expected to have yearly competence seminars on queer and gay perspectives, and government staff in management positions must attend ‘pink competence courses’ on sexuality and orientation. ‘But they can go their entire career without having to attend a single seminar about competence when it comes to racism, ethnicity and discrimination,’ Prestø adds.

He argues from a document drafted for schools on matters dealing with racism and believes it should form the basis of a legally binding file for arts institutions across the world. Such a file would detail protocol for racism incidents by and from audiences, employees, performers and hired external professionals, as well as for an institution itself accused of racist practices.

In 1999, a report produced by the UK government in response to the murder of Stephen Lawrence defined a racist incident as ‘any incident which is perceived to be racist by the victim or any other person.’ Simply abiding by this when speaking out, challenging racism or dealing with racial based concerns will go a long way to reduce gaslighting, dismissal, and further discrimination and instead increase professionalism, retention and tangible actions.

‘Once you have those things in place, you suddenly have power of definition,’ Prestø concludes. ‘This is what it means to be a Black person, this is what I need your space to have in place.’

Change and the RAD

‘Being anti-racist is actually being proactively inclusive. Are we being proactive enough?’ asks Shelley Yacopetti. The education and engagement manager of RAD Australia’s Faculty of Education is discussing how the RAD’s policies have been passive, and now need an injection of proactivity.

‘Teachers have a very amazing sense of influence over students,’ she adds. ‘They get to embed creativity, physicality, the love of movement. Imagine if they did that through the lens of racial equity. “Am I providing an inclusive environment for everybody? Are all of my students comfortable? Are their parents comfortable? Are they in an environment where they can thrive?” We realised that there was no checklist of what and what not to do.’

Yacopetti believes this starts with adequate staff training. ‘From there we can embed that into our education programme,’ she continues. ‘[Then] into our student events and activities to make sure that we are providing opportunities for everybody.’

The RAD has set up equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) working groups, to tackle such questions. On the anti-racism working group, Sue Bacchus, Head of Trading at the RAD in London for the past 14 years, acknowledges staff are fairly diverse but isn’t sure ‘that we make best use of our diversity.’ For progress to be made, she believes the organisation needs to confidently look inwards and gain the trust of its diverse staff who may still feel apprehensive about speaking out and offering solutions.

Sue Bacchus

Shelley Yacopetti

‘Teachers have an amazing influence over students. Imagine if they did that through the lens of racial equity’

Shelley Yacopetti

‘The way that you can gain people’s trust is by representation but also by speaking to your people,’ she says. ‘And that probably means, for the short term, anonymous surveys, until they believe you, and are comfortable that you’re actually going to listen to them. My outcome is for our organisation to be confident in looking inwards.’

Confidently looking inwards might also shine a brighter light on the few success stories. Céline Gittens, a former Genée gold medallist and current Birmingham Royal Ballet (BRB) principal, says her success is down to being treated equally with the awareness of her ethnicity. ‘There has never been another dancer of such diversity, a woman [at BRB],’ she says. ‘So there’s a thought that it could be that they were using me for the face of the company.’

‘But I don’t think that was the case, because I knew my level,’ she continues. In 2012, when she became the first ballerina of colour to dance Odette-Odile in Swan Lake in the UK, she considered ‘this is because of my hard work and also winning the RAD’s Genée competition.’ Gittens has never been made to feel that it was her responsibility to be accommodated. ‘My skin tone required a little bit of a darker shade, pancake for pointe shoes or dyeing for the tights,’ she says. ‘That’s the way that they made me feel safe and respected, and treated the same as everyone else.’

What racial equity means is for experiences like Gittens’ to become more frequent. To not rely on exceptional mentors and teachers but on infrastructure and protocol that ensures no matter who steps through the doors, dancers are made to feel safe, heard, accommodated and enabled to enjoy long careers. ‘Education and access is key,’ she concludes. ‘I want to continue to inspire and be the success story that creates a beacon of hope for these dancers.’

Isaac Ouro-Gnao is a Togolese-British multidisciplinary artist and freelance journalist.

What steps would make dance classes more inclusive and welcoming? What information would help you as a teacher?

Let us know