It’s a spring evening in Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, and I’m the sole, privileged audience at a rehearsal by Children’s National Ballet Potskhishvili. Dressed in their rehearsal blacks, the dancers range from nine to 15 years old. Hair neat and heads aloft, they run through the choreography of former professional ballet dancer Nino Katvelishvili, which combines classical ballet with rich folkloric dance traditions from across this ancient Caucasus nation.

The rehearsal space, in a school building on neoclassical Chavchavadze Avenue, is a short walk from Rustaveli, the central thoroughfare where mass protests erupted a few days earlier against a law which Moscow-leaning prime minister Irakli Garibashvili tried to force onto the Georgian statute. The foreign agents’ law sought to ban overseas charities and companies from operating in Georgia and would have affected the scores of arts organisations such as the children’s ballet who attract funding from foreign institutions and charities, says David Potskhishvili, 45, the company’s ballet master and himself a former professional dancer.

Children’s National Ballet Potskhishvili, or ‘Little Stars’, was founded in 1990 by Potskhishvili’s father Gelodi, a year before Georgia’s secession from the Soviet Union. Gelodi had danced through the dark years of Soviet rule and its censorship. All four of David Potskhishvili’s sons, aged seven to 16, are also current or former members of the child company. ‘Dance is not in my blood, it is my blood,’ he laughs.

Potskhishvili’s 15-year-old son Andria attended Tbilisi street protests in March as did many of the Little Stars’ children and their families which, says Potskhishvili, was ‘naturally scary’. For Potskhishvili’s generation the April 9 1989 tragedy – during which a pro-independence demonstration in Tbilisi was brutally crushed by a Soviet Army armed with spades, resulting in 21 deaths and hundreds of injuries – looms large. After three febrile days, however, this year’s protests forced Garibashvili’s populist Georgia Dream Party to withdraw the reviled legislation: a small success for liberal Georgians, for now.

Dance is inextricable from politics in Georgia, as it is across the former Soviet bloc, where Muscovite administrations have often used Russian ballet as propaganda. Ballet was used to forge political allegiances between Cuba and the Soviet Union in the Soviet era and Swan Lake notoriously played on loop across Russian television in 1991, during the attempted coup against Mikhail Gorbachev by hardline communists.

The war in neighbouring Ukraine brought 180,000 Ukrainian refugees to Georgia in the year to February 2023. They include dancers Olha Vidisheva, who joined Tbilisi Contemporary Ballet, and Evgeny Lagunov, who closed a defiant Georgian Culture Week at the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet State theatre in November 2022 by starring in Radio and Juliet, a ballet set to 11 Radiohead songs.

Like the region’s political history, the ballet traditions of Russia and Georgia are also deeply entwined. Vakhtang Chabukiani (1910–92) was born in Tbilisi and trained at the Vaganova Academy in St Petersburg, being hailed by the Soviet regime and influencing its dance traditions. However, he fell out of favour in World War Two when he played a folk antihero too sympathetically in a propaganda ballet, Taras Bulba, that had been forced on the Kirov (now Mariinsky) Ballet. Today Vakhtang Chabukiani Tbilisi State Ballet School, named for Georgia’s most famous dancer, continues the proud tradition of teaching classical Russian ballet.

Running a dance company in Potskhishvili’s father’s era, in the waning days of the Soviet Union, remained a dangerous act of defiance. Potskhishvili recalls, ‘my father risked a lot to keep up in dance through the Soviet time. Even though Stalin was Georgian, the Soviets did not like any culture that was about Georgian nationalism. The adult company was censored by the communist party machine into the 1990s.’

Little Stars’ name, according to the company’s origin story, was inspired by dissident Soviet ballet superstar Rudolf Nureyev’s comment at an early performance by the young company in New York, a few years before his death. ‘I want to thank Gelodi Potskhishvili and the team of the choreographers who have prepared these little stars so professionally,’ Nureyev is reported to have said. He was presenting emerging dancers at an event, Potskhishvili tells me, at which he was too frail to dance himself.

In the rehearsal room at Chavchavadze Avenue, the music strums into a crescendo of Georgian panpipes as dancers part like a supple wave and 12-year-old Marisha Loladze takes the stage. Loladze dances ‘jeyran’, a twirling female dance with febrile footwork, elegant outstretched arm positions and fluttering hands that combines classical ballet with hunting dance traditions from the southern Caucasus. It is said to call to mind the gazelle, the light-footed antelope native to southern Georgia; but also its hunters, who traditionally stalked it with spears.

Loladze would like to join an adult company one day. Jeyran is her favourite dance, she tells me later. ‘It combines techniques from classical ballet and Georgian national dance with elements of the hunting ritual, resulting in a unique performance,’ she adds. ‘In Georgia we believe that you have to dance the jeyran very well to prove you are a good dancer and it suits my personality too. Sometimes my family and friends call me jeyran!’

Georgia lost territory to Russia during the 2008 Russo-Georgian war, when South Ossetia and Abkhazia ceded to Russian occupation, a fact that still rankles with many Georgians. In recent concert programmes, Little Stars have presented folk dances of these two ancient regions (Abkhazia is seen as the cradle of Christianity in Georgia, which took to the religion in the first century): the java hunting dance of South Ossetia and musera, a martial dance from Abkhazia. The company performs in regional traditional costumes in vivid colourways.

‘We [perform these dances] in the fervent hope that these territories will one day be returned to Georgia,’ Potskhishvili says of his decision to stage the dances as an ongoing gesture of political protest in the company’s programmes. ‘These territories are shown on ancient maps to be ours; and are ours in our hearts.’

Nine-year-old Kirile Oqrokvercxisvili fixes me with an enthusiastic smile as he springs forward on pointe. Oqrokvercxisvili is a favourite with Little Stars audiences: tiny and spry, but with the power of a dancer three times his age. He tells me that Little Stars is the ‘coolest troupe in the world,’ and particularly loves dancing a character called Mamber in the concert that Little Stars will tour from September. Mamber, he says, is a young boy with ‘a strong and fighting spirit, who [has] many adventures and finally regains the honour of his family.’ It’s a tale based, Potskhishvili tells me, on an old Georgian coming-of-age folk legend: ‘we need our folk stories now more than ever.’

‘We perform dances from territories that are ours on ancient maps, and in our hearts’

David Potskhishvili

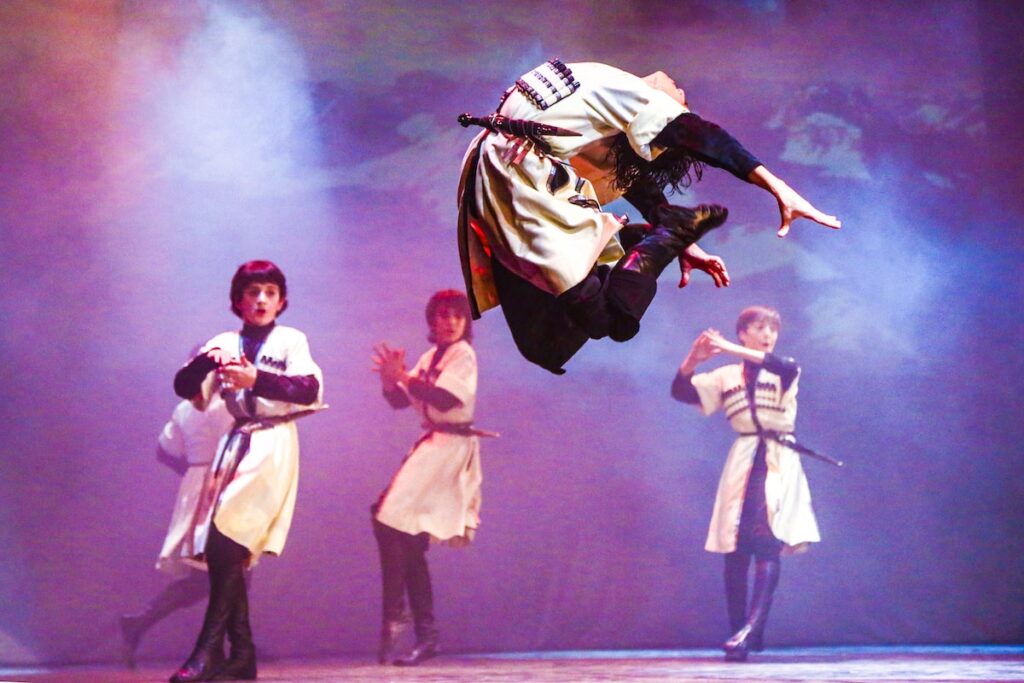

Next up is a performance of the South Ossetian java. Danced by boys with cossack-like military posturing, darting spins and lunges, java is both martial and strangely uplifting.

The challenge in melding traditional ballet and Georgian folk dance traditions, says choreographer Nino Katvelishvili (a former professional ballet dancer and Potskhishvili’s wife), is the male dancers’ legwork. ‘There are lots of strong leg positions in folk dances and lots of squatting which can be hard on young legs,’ she tells me. ‘It is also difficult to mix these seamlessly with classical ballet positions – going from tense muscle work to the open position of ballet.’

Potskhishvili, for his part, sees Georgian folk dances and classical ballet as ‘oil’ and ‘water’. ‘Ballet is very mathematical. In ballet two plus two equals four. In folk dance it is 70 percent about emotion: what are you saying about the local character in the dance? Who or what is your war dance for?’

Katvelishvili admits that some emotions the folk dances are designed to convey – aggression, nativism, nobility against the odds – can be tough for younger dancers to grasp. The strongest and most martial dances hail from the mountain borderlands with Russia, where the territory is harsh and the threat of invasion ever-present. Sagalobeli, a folkloric tradition from another border region in which young boys dance with swords, can prove too much for audiences, Katvelishvili admits. ‘We can have negative reactions to sagalobeli. But it is a dance that comes from our history and our territory with good reason.’

‘I would like Georgian dance to become as well known as ballet. It is the dance of the gods’

Cotne Gabadze, 12

The RAD adult dancer Sophie Rebecca met Little Stars when she was performing at a competition and gala called Ballet Beyond Borders in 2019. ‘What struck me was the ferocity of their performance,’ she recalls. ‘The boys were hurling themselves at each other with swords and shields in this traditional warrior dance where they battle at such pace.’ This is starkly contrasted with the female dances, Sophie says. ‘These are more about creating serene shapes and moves, reminiscent of a swan gliding on water. At times they were doing this as the boys fought all around them, swords flying: it was quite unique, even in the cultural melting pot of Ballet Beyond Borders.’

Java is also Cotne Gabadze’s favourite dance. The 12-year-old Little Stars dancer describes it as ‘volcanic’. ‘People can easily see the culture and character of the mountainous regions of Georgia in the dance,’ he says. ‘It evokes strong emotions in me and I do my best to express myself in it.’ Gabadze tells me he would like to become a professional dancer and an ambassador for Georgian dance. ‘What I would like is that Georgian dance become known all over the world and be as well known as ballet,’ he says. ‘It is the dance of the gods.’

Nodar Khutidze, 12, also loves to dance java. He is weighing up whether to pursue a career in dance or in the Georgian boom industry of wine-making. Dance for Khutidze is a form of communication, across national boundaries but also of national character. ‘When you dance, you have to tell some kind of a story, not with your voice, but your body and what you mimic,’ he explains. ‘Dancing is not just art. You can dance and make important statements about the world with your movements.’

Potskhishvili, who says that dance is ‘a challenging life, and a narcotic,’ doesn’t push his charges to become professionals, though many are on this route. ‘They have to decide what future awaits them,’ he says. He hopes that, whatever the fate of the 50 young dancers in his ensemble, it will be played out in peacetime rather than through the turbulence of his own childhood. He tells me that he supports Ukrainian dancers’ repudiation of Putin by dancing in Ukrainian national costume and in exile: ‘They must dance and we must dance too.’

Watch

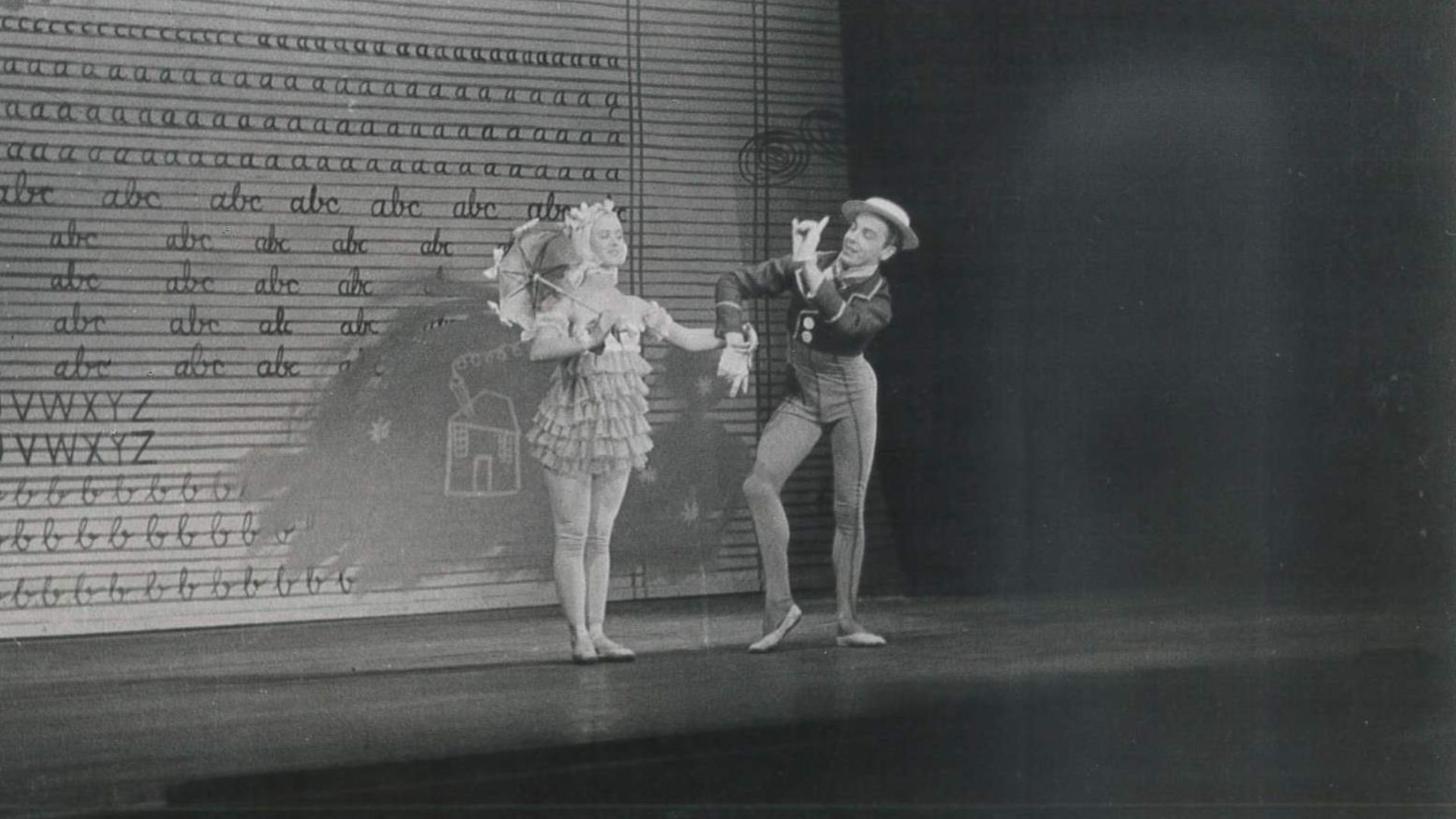

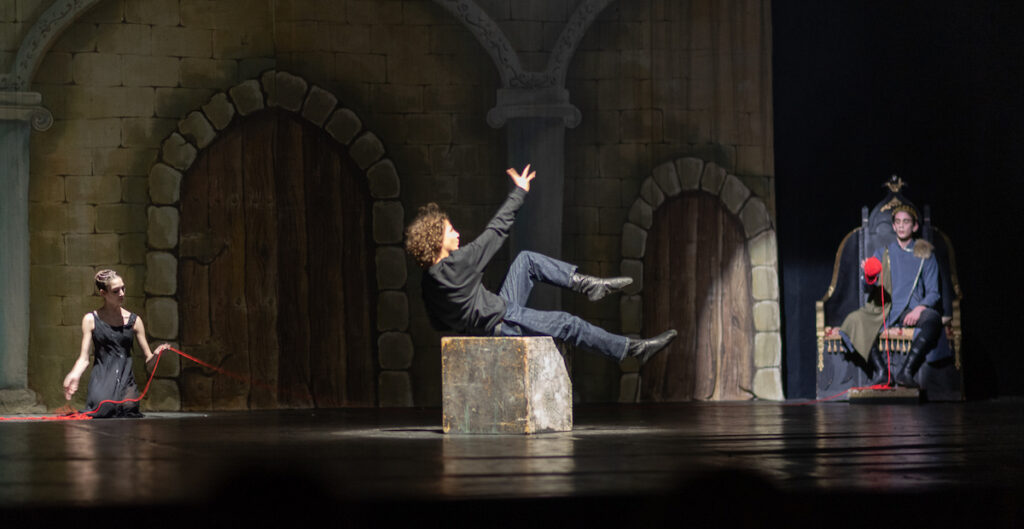

The Little Stars in rehearsal

Sally Howard writes for the Sunday Times and others, and is author of The Kama Sutra Diaries and The Home Stretch.