Recent years have witnessed a significant shift in the representation of disabled dance artists. In popular culture, television shows like BBC’s beloved dance competition Strictly Come Dancing have welcomed contestants with different disabilities: actor Rose Ayling-Ellis, who is Deaf, and comedian Chris McCausland, who is blind, won in 2019 and 2024 respectively.

Yet, despite pioneering organisations like Candoco, which includes both disabled and non-disabled performers, the former rarely secure positions in mainstream companies. However, in 2022, South African dancer Musa Motha, who started dancing with crutches after losing a leg to bone cancer, joined Rambert, the UK’s oldest dance company. He later reached the finals of TV talent competition Britain’s Got Talent and performed in the opening ceremony of the 2024 Paralympic Games in Paris.

For many years, such representation has been rare. Australian-born, Scotland-based dancer, choreographer and artistic director Marc Brew trained at the Australian Ballet School before beginning his career in South Africa. Then, a car crash that was fatal for his three friends left him paralysed from the waist down. After a return to Australia and a challenging recovery, he was keen to continue working with movement. Yet he’d never met any other disabled dancers and his previous companies were unsure how to work with him. ‘It had been drilled into me, this ideal of what a dancer is – shape, body form, flexibility, technique,’ says Brew. ‘I didn’t fit that mould anymore.’

‘I’m in a place I’ve always wanted to be, but I never felt worthy’

Marc Brew

When friends connected Brew with New York-based Kitty Lunn, who adapted ballet and other techniques into her wheelchair, he began to see a path forward. He has since forged an impressive career, dancing with Candoco (where he felt ‘seen as a dancer again’), choreographing for Australian Ballet Company and Candoco, and taking directorial positions at AXIS Dance Company and Scottish Dance Theatre. His work explores ‘how restriction creates new and interesting possibilities for movement’ and requires his dancers to bring their whole selves, not just their dance personas: ‘I want them to be honest with every move they make.’

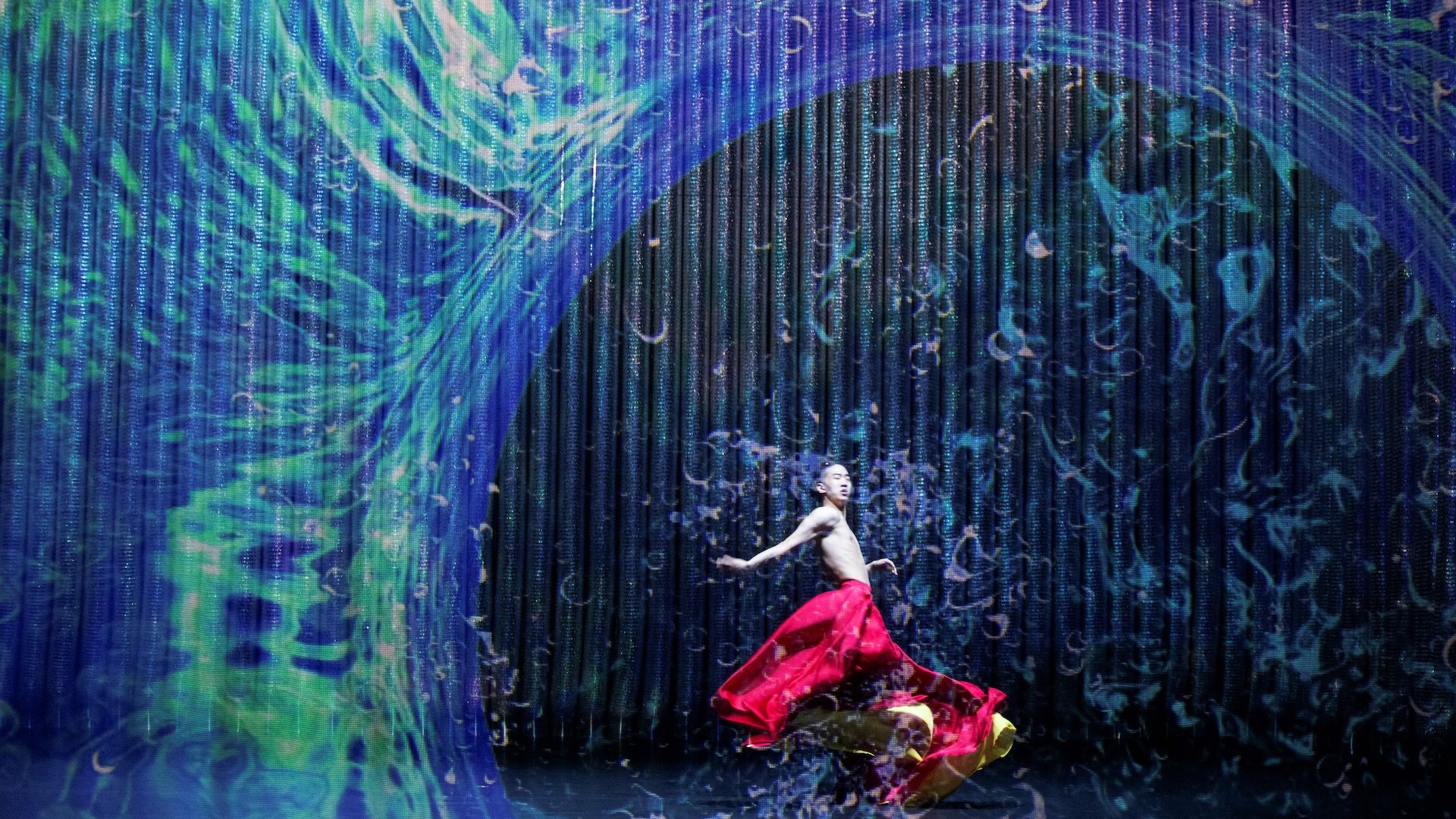

Despite his achievements, a sense of imposter syndrome has stuck with Brew. His solo show, an Accident/a Life, which premiered at Holland Dance Festival last year, relates the aftermath of his life-changing accident. It was planned as a duet with his creative collaborator Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, until the renowned Belgian choreographer decided his narrative would dilute the power of Brew’s. ‘He felt my story deserved to be on these main stages and be told by me on my own,’ says Brew. ‘I really appreciated that. It comes from my own insecurities and experience of being a disabled artist – I didn’t feel I was worthy. Working with Larbi has taken me to a place I’ve always wanted to be, but never felt I had the right or permission.’

Brew isn’t the only artist navigating such insecurities. London-based hip hop and street dancer and choreographer Chris Fonseca, who is leading workshops with the RAD this year, admits he used to wear a hat to hide his cochlear implant. One day, he was asked to remove it to enter a club with a dress code. ‘I decided to embrace my identity,’ he says, interpreted from BSL by Harry Jardine, his co-artistic director of Fuse Theatre.

This experience directly translates into a scene in Follow the Signs, Fonseca and Jardine’s hip-hop gig theatre show that premiered at London’s Soho Theatre in 2022. It recounts experiences from Fonseca’s life and his multi-layered identity as a Black Deaf person. ‘I’d always identified as Deaf and Black,’ says Fonseca. When he encountered racism within the Deaf community (which, he stresses, is not homogenous), ‘it was like: wow, my own community can be racist against me. I started to realise that actually I’m Black first and Deaf second.’

‘Often disabled bodies are watched for inspiration porn’

Diana Niepce

Fonseca and Jardine hesitated to address race in Follow the Signs, concerned that it might be inappropriate for Jardine, who is white, to voice Fonseca’s experiences as a Black person. ‘Then we thought, this goes against everything we’re trying to do. I was limiting him telling his truth,’ says Jardine. Addressing the topic opened up conversations about the lack of diversity among BSL interpreters in the UK. ‘Often, when Chris books an interpreter, it’s a white woman, so he doesn’t feel the audience are getting his voice,’ Jardine explains.

The work of artists like Brew and Fonseca not only helps break down barriers for other disabled artists, but the dance world as a whole. ‘We bring different perspectives and creative processes,’ says Brew, who applies the same care-based, inclusive practice with both disabled and non-disabled dancers. His ‘rituals’ include twice daily check-ins to discuss what the dancers need to work productively (‘I don’t just want to work with them as bodies, but as humans’) and regular ‘bio-breaks’ to service their unique biologies. ‘It’s about access, but also influences the work we make,’ says Brew. Some dancers initially feel ‘uncomfortable and exposed’ by the approach, but in the end, ‘if I don’t do it, they miss it.’

Audiences benefit too. Fonseca believes integrating BSL into his choreography enhances understanding for all viewers. In her recent solo show Songs of the Wayfarer, Glasgow-based dancer and choreographer Claire Cunningham, who explores the ‘use and misuse’ of her crutches, opens with a scene in which she acts like a mountaineering guide. She informs the audience of the different ‘conditions’ they may experience during the performance. ‘A lot of non-disabled theatre makers resist things like content warnings, saying they spoil the work,’ Cunningham told me on the dance podcast Terpsichore. ‘But we can challenge audiences with provocative things but still take care of them.’

Tackling challenging topics is important for Portuguese choreographer Diana Niepce. Trained in ballet, contemporary dance and circus, Niepce started to work with disabled dance companies in 2014 when an accident left her quadriplegic. Frustrated at the focus on beauty and celebration in the disabled dance scene – ‘often disabled bodies are watched for inspiration porn’ – she started making her own work on topics such as violence, oppression, and bodily objectification. She uses circus practices such as contortion and suspension and doesn’t use wheelchairs or crutches to support her movement. ‘I want to present my body as it is. It has its own specificities and practices.’

‘We’re artists: we deserve to be seen for our work instead of just our disabilities’

Chris Fonesca

Niepce’s latest show, The Other Side of Dance, was performed at London’s Southbank Centre in the Dance Umbrella festival last year. Described as a ‘survey of the invisible in dance history,’ it pays homage to pioneering disabled artists like Cunningham and David Toole, a double amputee who performed with companies such as Candoco and DV8. ‘I wanted to bring their voices alive again,’ says Niepce. ‘We don’t communicate as much about disabled artists as about normative artists.’

This lack of communication is starting to change: disabled artists are leading the charge to get recognition for their contemporaries. Together with Deaf actor Nadeem Islam, Fonseca and Jardine created A Night of Sign, a BSL-led cabaret of music, dance, comedy and poetry. Performed at theatres including the Globe’s Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and Streatham Space Project since 2020, it showcases talent across the Deaf community. ‘Deaf artists are there, seriously talented, and ready to be employed,’ says Fonseca.

While Fonseca appreciates growing representation, he is wary of tokenism. ‘We’re artists, and we deserve to be seen for our work instead of just our disabilities,’ he says. ‘When [our presence] becomes a box-ticking exercise, it separates us even more, when we should be trying to celebrate each other.’

Other issues include normative choreographers working with disabled dancers for one off projects rather than long term, and a lack of disabled artists in leadership roles. Brew cried with happiness when last year’s Strictly final featured two people who identified as disabled. ‘But where’s the person with a disability on the judging panel? That’s where we’re still so far behind,’ he says. He adds that national, government-funded organisations need to make a greater commitment to engage with disabled artists in order reflect the diversity of the countries they represent, and offer role models for younger generations.

‘If I hadn’t acquired my disability, I wouldn’t have faced these challenges,’ says Brew. ‘It might have been easier to achieve what I have.’ However, ‘being disabled has helped to build who I am as a person.’ It’s crucial that disabled artists keep working on prominent platforms. Fonesca recalls a family telling him and Jardine that seeing Follow the Signs inspired them to learn BSL to better communicate with their Deaf child. ‘That was an amazing moment. It’s why we do what we do.’

Emily May is a British-born, Berlin-based arts writer and editor specialising in dance and performance.