March 2025: 15 young women watch Tara Ghassemieh adjust her laptop camera and adopt first position in her sunlit southern California dance studio.

‘So you’re always going through first – en dehors is like opening the door and en dedans is like closing the door,’ says Ghassemieh, recently a guest principal with Golden State Ballet in San Diego. ‘Think as if you are stirring the soup, stirring the soup, or,’ she laughs, ‘your ghormeh sabzi [the Iranian national stew]!’

The watching women wear leotards and t-shirts, with kitchen counters and the backs of dining chairs standing in as makeshift barres. It might be one of the myriad Zoom ballet classes of the lockdown years, were it not for the fact that dancing behind closed doors and pulled curtains has been an everyday reality for aspirant ballet dancers in Iran, where Ghassemieh’s students are based, for over 40 years.

Ghassemieh’s Dancers of Iran online class is just one of the 36-year-old Iranian American dancer’s projects to open up opportunities for aspiring dancers in her father’s homeland. ‘You tell dancers in the US that dancing ballet is illegal in Iran and grounds for arrest and they look at you as if you’re crazy,’ she says. ‘But you only have to look at what is happening now in US cultural institutions to realise that everywhere we have to fight for the freedom to dance.’ In 2024, The White Feather, Ghassemieh’s ballet about a dancer coming of age in the Islamic Republic, appeared at Washington’s Kennedy Center. Now chaired by Donald Trump, the Center has dismantled the diversity initiatives which programmed the ballet. ‘I don’t think The White Feather would be staged at the Kennedy Center now,’ Ghassemieh says.

‘If you tell people that dancing ballet is illegal in Iran, they look at you as if you’re crazy’

Tara Ghassemieh

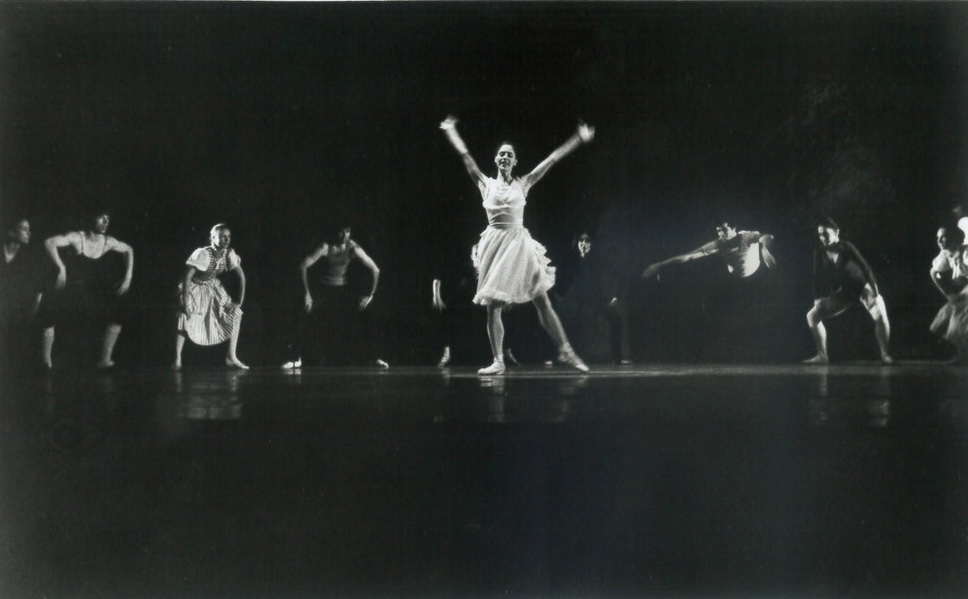

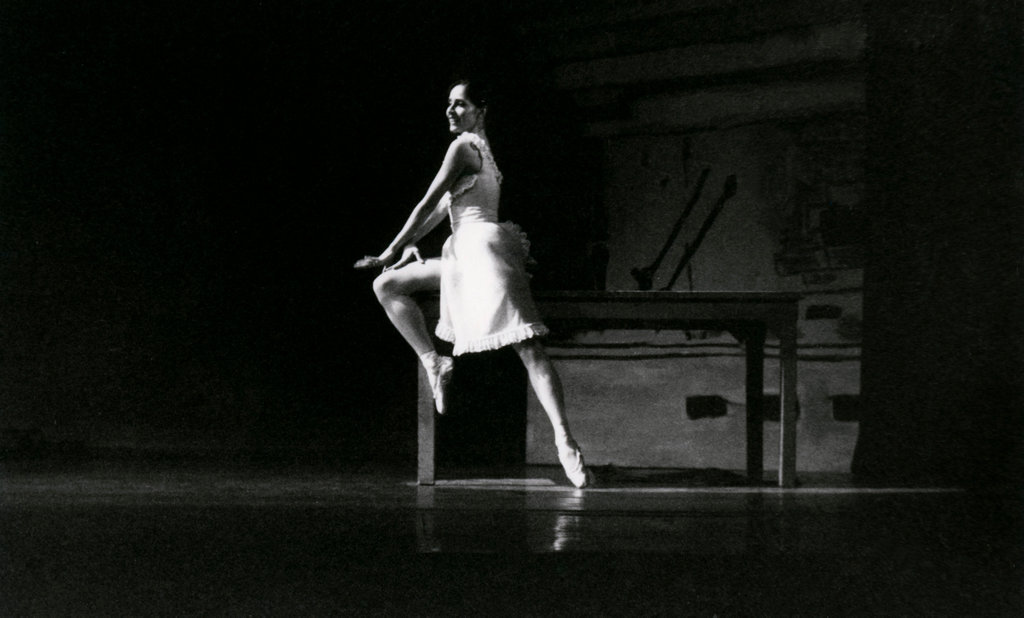

The White Feather opens in 1979: as the Iranian National Ballet rehearses Swan Lake, a dictator stalks onto the stage and makes the women remove their pointe shoes and dress in hijabs. A general fights back and is executed on stage.

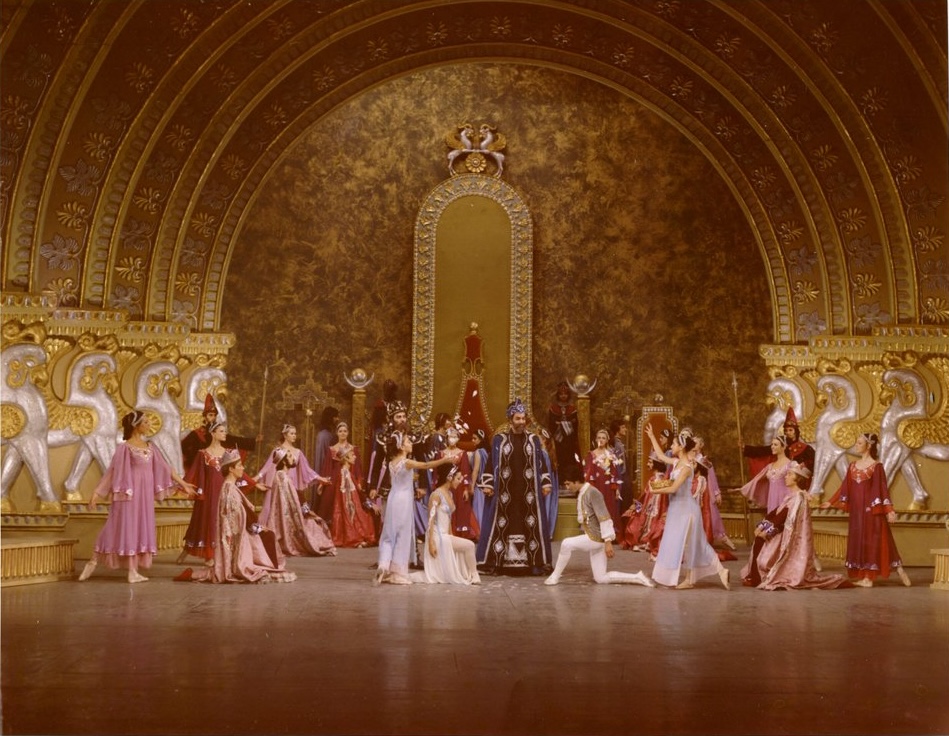

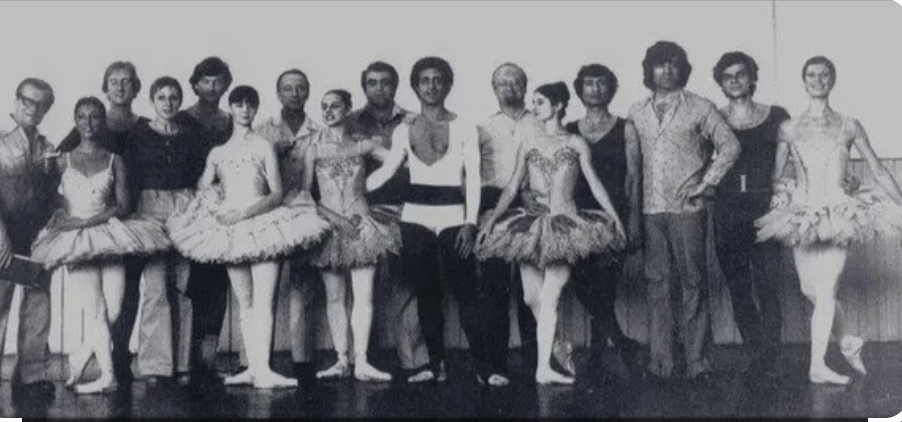

These scenes aren’t hyperbole, Ghassemieh assures me. The Iranian National Ballet was in its heyday when, during the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the ruling Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was overthrown and the country became a hardline Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. ‘The 1970s was a golden age,’ Ghassemieh says. ‘Margot Fonteyn and the Martha Graham Company toured Iran and the Queen and Shah brought in international dancers.’

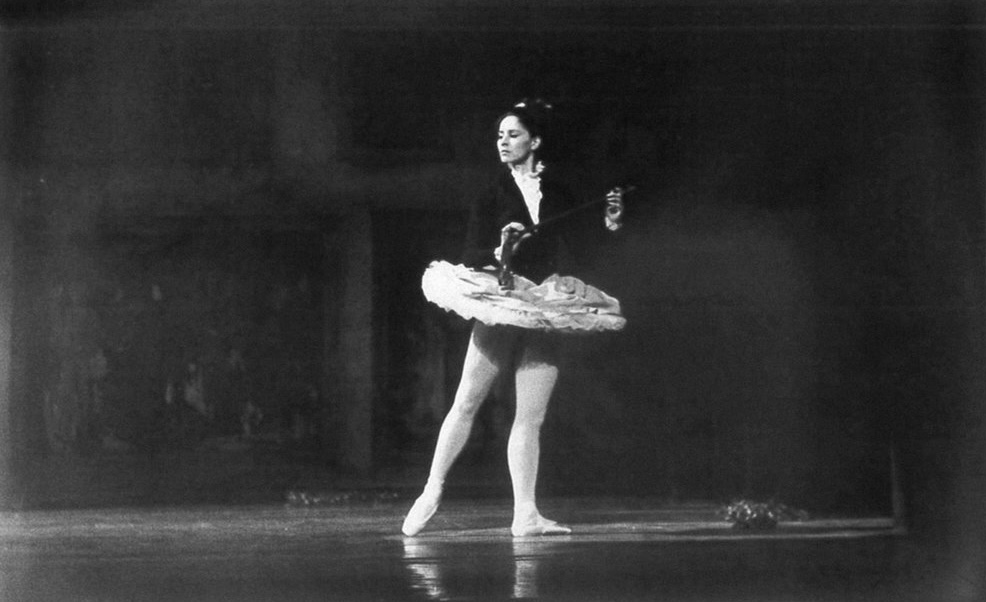

RAD graduate Bahareh Sardari, now in her seventies, was amongst Iran’s last professional dancers: a soloist with the Iranian National Ballet Company when the company dissolved and its sets, costumes and archives were burned as dancing in public was outlawed. ‘Finito,’ Sardari has said of the day the ayatollahs decided that ballet was ‘incompatible’ with the Islamic republic. ‘It killed my heart.’

Iran has been a cradle of dance since prehistory, from the spiritual dances associated with the cult of Mithra, to Bandari dance, often referred to as Persian belly dance. Nima Kiann, an Iranian-born Swedish ballet dancer and historian, told me, ‘Iran, as one of the ancient world’s empires, was devoted to the development of the art of dance.’

Sadly the Middle East also has a long history of banning dance. In Islam, extreme salafists and wahhabis consider dancing in any form to be haram (forbidden). The spread of Islam from the 7th century introduced a more conservative approach to public behaviour, with some religious authorities viewing dancing as immoral or a distraction from spiritual pursuits. Such censure has resurged in recent years. Kuwait forbids residents to dance in public places, with punishments including arrest and imprisonment. In Afghanistan the Taliban has publicly beaten dancers and musicians since the theocratic state regained power in 2021, when it banned both dancing and music performance.

March 2025 in Tabriz, a city in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran, and six teenaged dancers excitedly bounce across the sprung floors of a clandestine ballet studio, ballet shoes swinging by their ribbons from dancers’ wrists. Aydance Ballet Studio operates behind full lace curtains, with dancers arriving in modest clothing before changing into leotards and tights. The students’ and teachers’ names are concealed on social media, as is the studio’s street address. ‘As a dancer, I could tell you the most beautiful story without saying a word. That’s my power,’ reads a post on the studio’s Instagram account with a picture of three Iranian girls sitting in ballet shoes and modest dress on a park bench in Tabriz.

The school’s manager, who I will call Afsaneh, is an Armenian Iranian who did not want to use her full name. She told me that, as a Christian, she feels less bound by anti-dance diktats, but that her school walks a fine line: operating on the margins of the law while trying to attract pupils. ‘We hide our address and let parents tell other parents about us,’ Afsaneh says. ‘We know we could be raided at any point.’ For the self-taught teacher, there’s also the challenge of keeping up to date. ‘Online classes help teachers, but there is no replacement for learning in person,’ she says.

Ghassemieh worries that poor practices are shared in underground Iranian ballet schools by well-meaning teachers who have taught themselves on YouTube. ‘A lot of damage can be done with bad teaching,’ she says, ‘so my next plan [as part of Dancers of Iran] is to set up a programme to teach the safety basics online to underground teachers.’

Much of the energy of Iran’s underground dance movement has come from the wave of protests that broke out from 2018 when Maedeh Hojabri, then 18, was arrested for social media posts in which she performed a form of cabaret dance. She was forced to publicly apologise for indecency on state television. The #zanzendegiazadi (woman, life, freedom) movement grew after the death of Mahsa Amini, arrested by morality police in 2022 for not wearing her hijab properly and who later died in a Tehran hospital under suspicious circumstances.

‘We hide our address – we know we could be raided at any point’

Afseneh, dance school manager

Under the Iranian Penal Code, dancing in public can be punished by flogging (specified as 99 lashes); yet defiant videos and pop-up dance protests broke out after Amini’s death, including a mass event in a Tehran underpass. In 2023 five teenagers were arrested for dancing without headscarves on TikTok to celebrate International Women’s Day and in January 2025, two teenagers were arrested for posting a dance sequence performed on a war memorial.

A Tehranian dancer who did not want to be named and attended the Dancers of Iran online class in March, told me that she first came across Tara Ghassemieh when the Californian posted a video dancing alongside footage of an Iranian protestor. She had childhood aspirations to be a dancer and hopes dance-as-protest will bring a new generation to dance. ‘It is too late for me, I hope it will not be the case for younger Iranian sisters.’

One note of optimism comes from underground dancers’ willingness to reach out to western professionals. Yasmine Naghdi (Royal Ballet) and Tiler Peck (New York City Ballet) have both been contacted by young people practising in secret: in one case in a disused swimming pool on the outskirts of Tehran.

Peck says that her Covid lockdown classes led to many such approaches. ‘During my #TurnItOutWithTiler classes I had dancers reach out on Instagram, letting me know they are not allowed to dance in their country, but that my classes allowed them to dance in the comfort of their own home. It felt like an escape for them – this really touched me,’ she recalls.

Nima Kiann, the dancer and historian, draws hope from the fact that, 46 years after Iran’s theocratic regime suppressed it, dance remains vibrant in his home nation: ‘one of the most widespread means of protest and a sign of the new generation’s request for change,’ he says. ‘The passion for ballet, even in hidden forms, is a testament to the enduring power of art and expression.’

In California, Ghassemieh is composing a new piece, Azadi (‘freedom’). Mixing traditional Persian dance elements with ballet, she intends it to launch her new international Iranian diaspora ballet company next year. Her dream is to bring young dancers over from Iran to join the fledgling company, but knows they would risk arrest on return. For now, Iranian members will contribute snippets of choreography from afar.

Last year, Shahbanou Farah Pahlavi, the exiled former Queen of Iran, attended The White Feather at the Kennedy Center. Yet the true stars of the evening were Bahareh Sardari, Mary Apick and Robert DeWarren, three dancers who in 1978 performed in the Iranian National Ballet’s The Sleeping Beauty, the company’s final show before the shutters fell.

‘I almost passed out,’ Ghassemieh says of the moving reunion. ‘But moments like that make me sure that we should fight on. That dance will one day come home to Iran.’

‘Dance is a means of protest and a sign of the new generation’s request for change’

Nima Kiann

RESOURCES

Sally Howard writes for the Sunday Times and others, and is author of The Kama Sutra Diaries and The Home Stretch.