Wearing a red cropped top and one of his famous merkins, Leigh Bowery aims a high kick directly at us – or rather, at John Maybury’s camera in 1989, captured in the video Leigh Bowery dancing. Bowery’s high kicks were legendary, expressing both his physical movement – as a baroque 6’3” performer who was often masked or made-up from top of the head to platformed toe – and his dynamism as he moved from suburban Melbourne to London and onwards, seeking and finding stardom. He was borne on an ecstatic tide of post-punk and pop music and fashion: famously on stage, choreographed by Michael Clark, but first in London’s queer nightlife, where Bowery met Clark and many others, and where dance was part of the atmosphere of sex, drugs and disco.

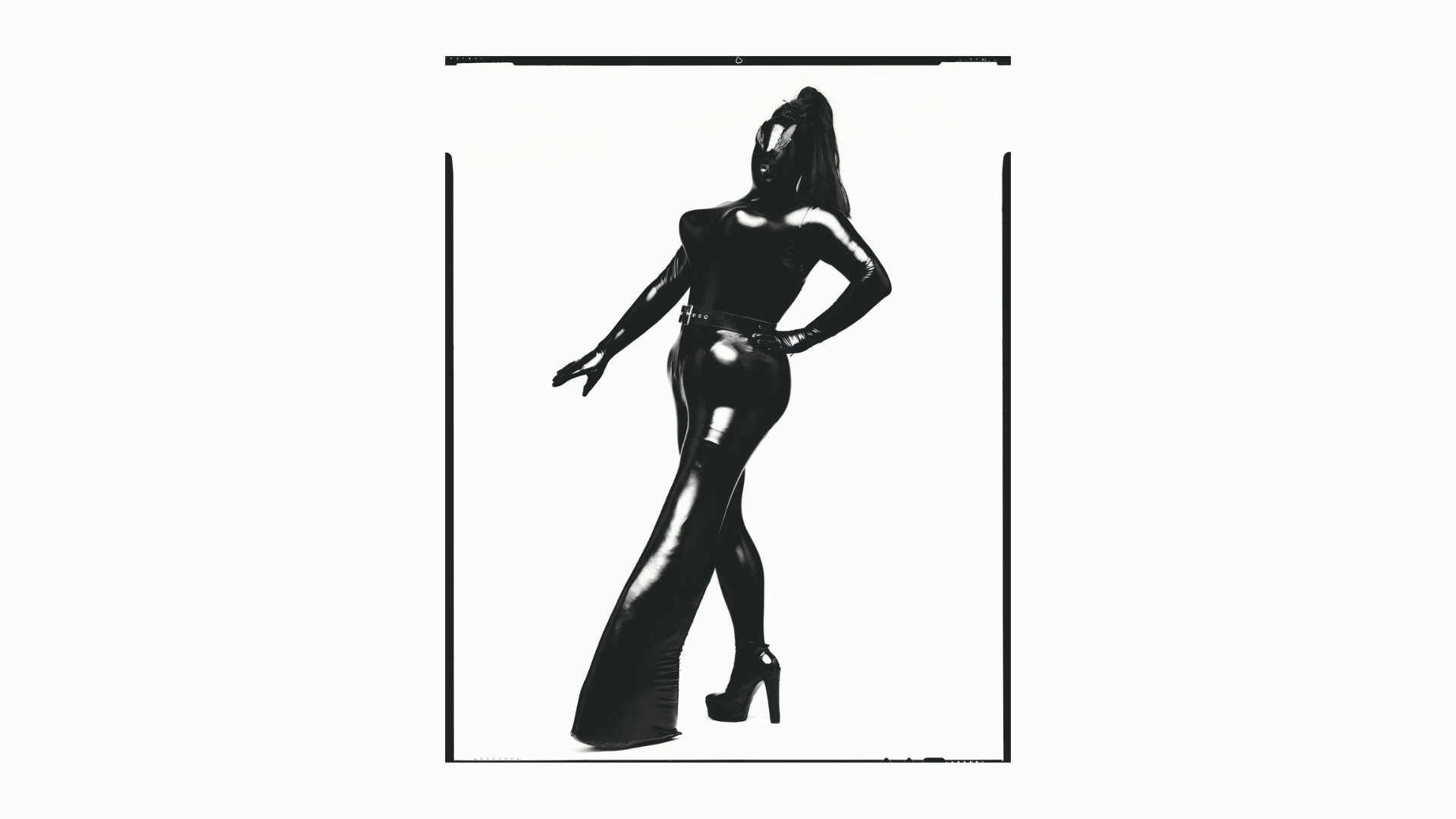

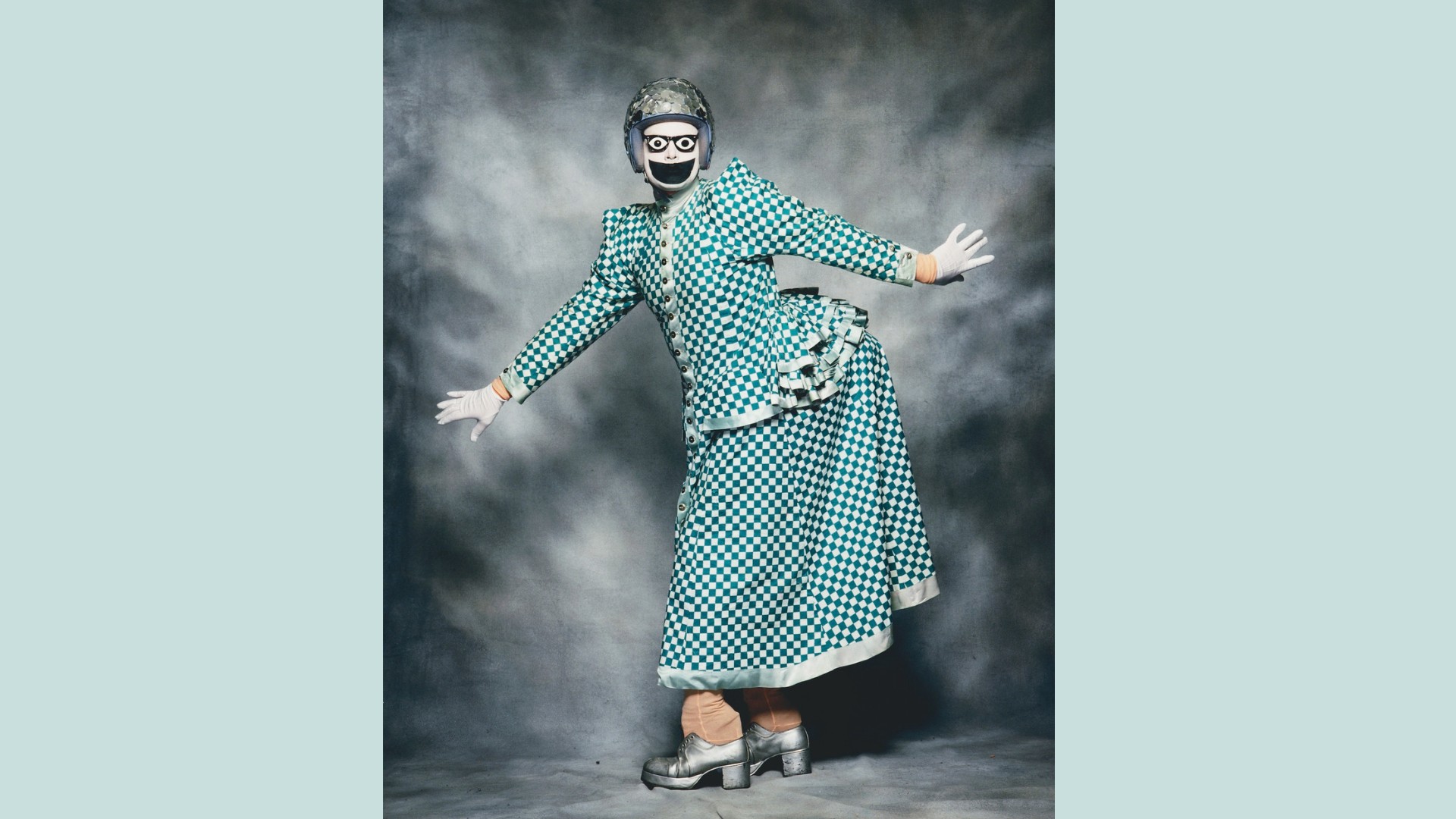

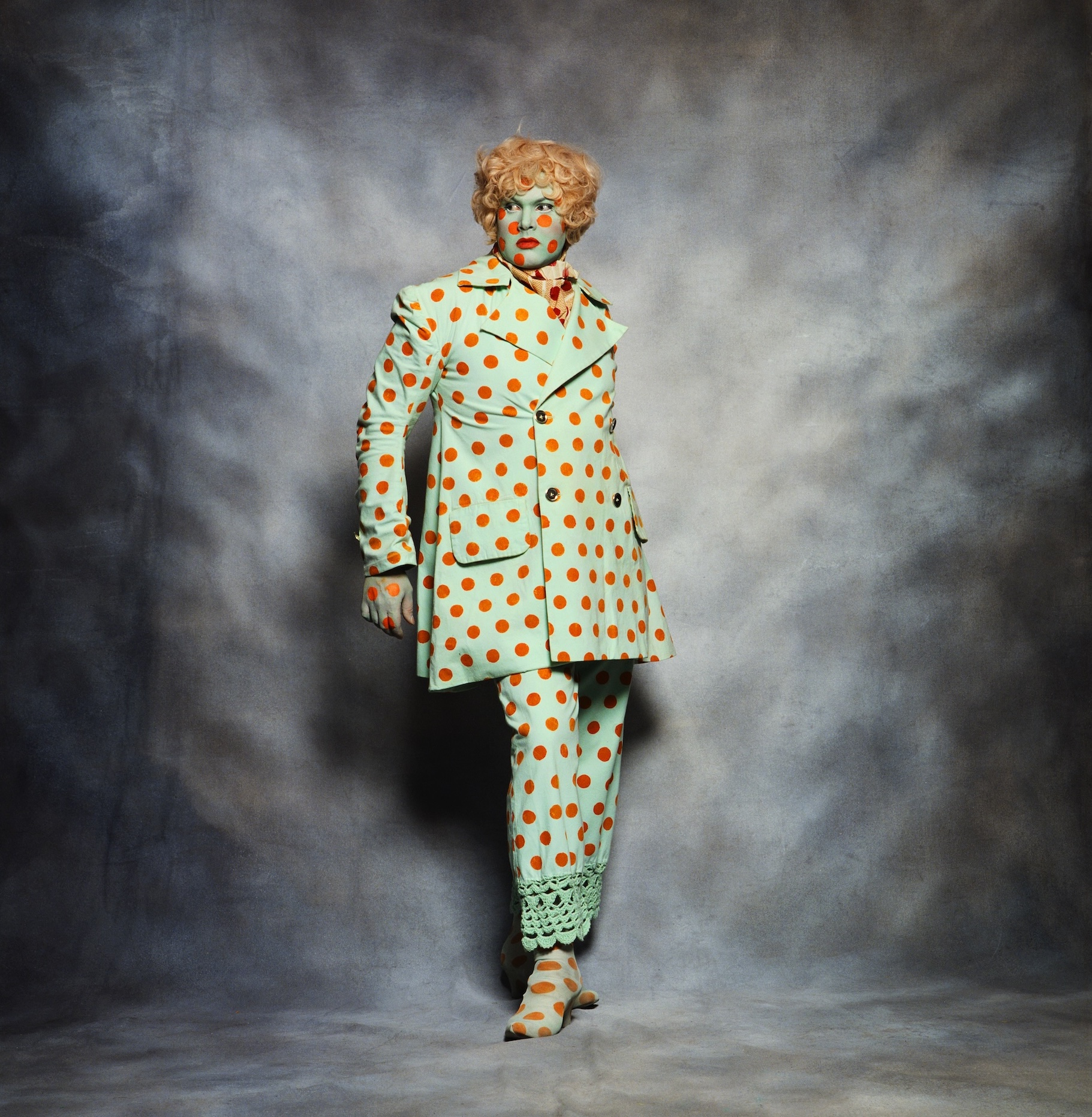

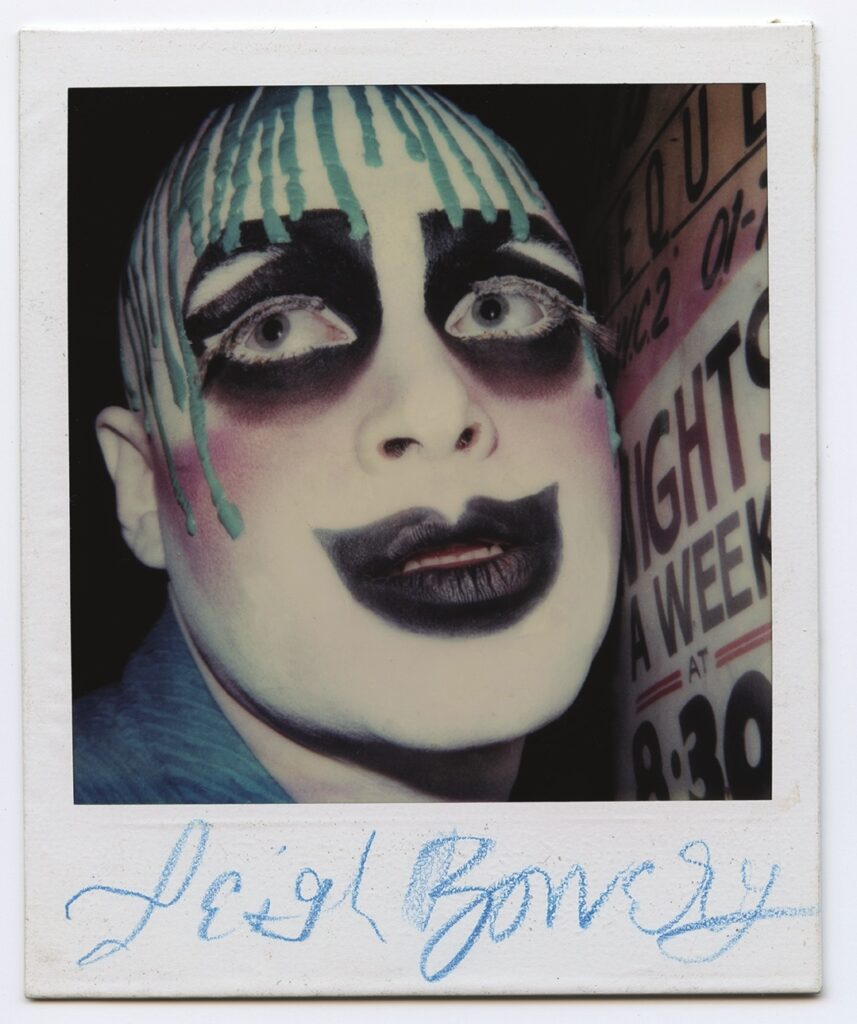

Taboo, the London club night that Bowery co-founded with Tony George in 1985, four years after his arrival in London aged 20, was a place to be seen – and Bowery, with Easter-egg shade polka dots covering his skin or crayon melted from his crown over white face paint, led the way. Sue Tilley, his close friend and Taboo coat-checker, writes in her memoir that ‘the ceiling of the cocktail bar was fairly low so with his platforms on Leigh was able to do a high kick and smash the lights above the bar.’ In 1989, he was arrested for doing high kicks in the middle of Charing Cross Road, weaving between vehicles on his way from one club to another. A few years later, in Charles Atlas’ film Mrs Peanut Visits New York, he strides through Manhattan’s West Village in a fabulous circus-striped jumpsuit, foam-padded to a Godzilla-like scale.

Hilton Als writes that Bowery ‘never asked a performer to wear what he hadn’t worn himself’ on the dance floor, which – given towering platforms and glued-on merkins – did not necessary mean physical comfort, but did mean costume design with spectacular movement in mind. Sequinned tights designed by Bowery for the Clark company, hand-sewn by his wife Nicola Rainbird, were only lightly spangled on the knees, notes dance historian Alistair O’Neill: all the better for kicking up your heels.

High kicks were a hallmark too of Clark’s thrilling, subversive, gender-blurring and boundary-crossing choreography. On magazine covers, on posters and in press shots, Clark is depicted in full extension, often in a kilt or hot pants, an exuberant gesture to both his classical ballet and Scottish dance training. Clark told Tilley that ‘people in clubs thought it weird that I could really dance… like if I kicked my leg high in the air it was part of my nature.’ He and Bowery met in their desire to subvert the assumed-natural and the everyday.

‘Bowery and Clark scattered formal dance into the everyday like glitter’

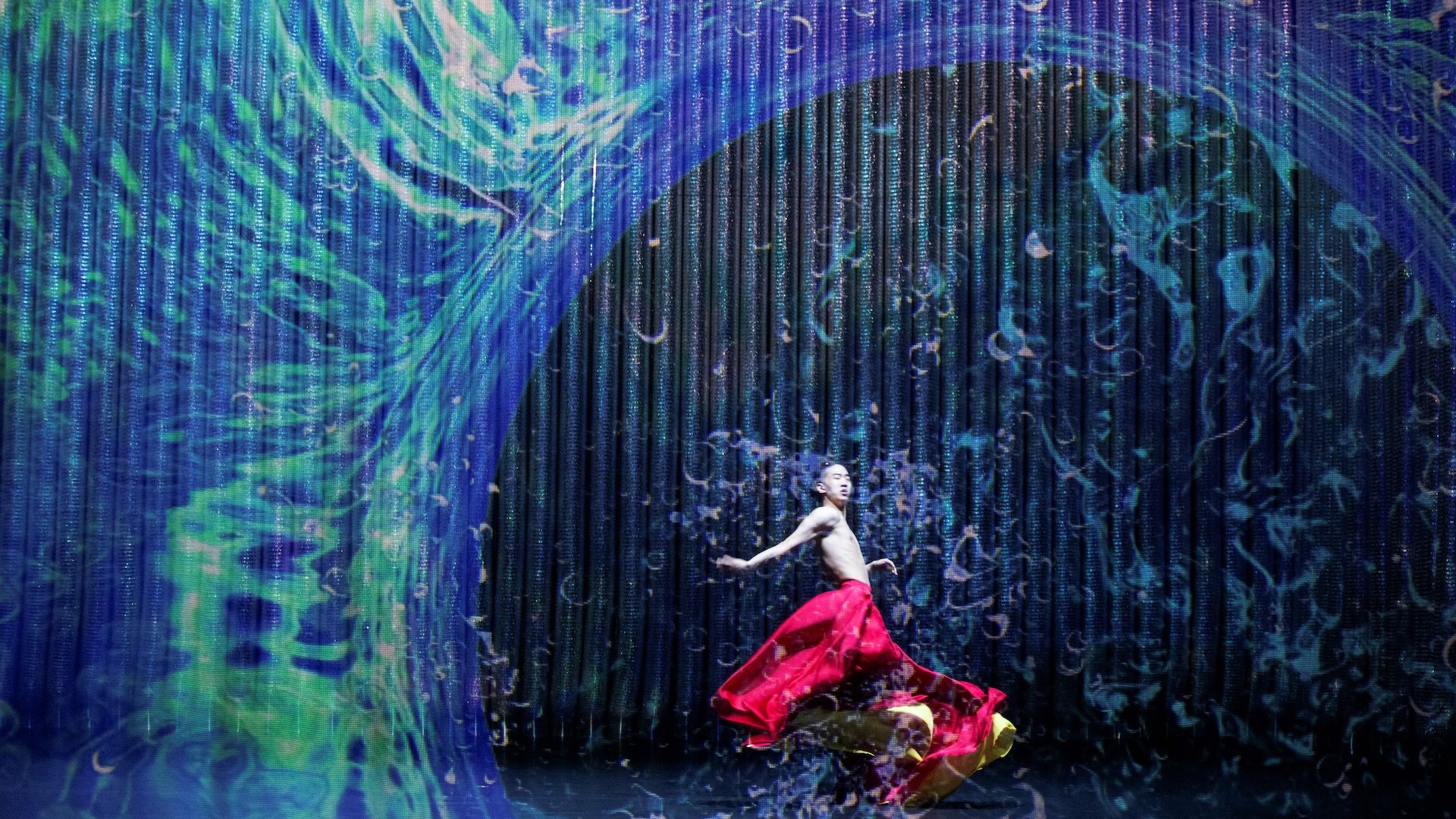

Atlas’ film version of Because We Must, the first Clark show in which Bowery was a listed performer with set choreography, shows how the pair inverted the Judson Dance credo of everyday movement on stage by scattering formal dance into the everyday like glitter. In a dreamy sequence filmed in the living room of a flat, the statuesque Bowery lifts four dancers layered atop each other on his back, with a deep graceful bend. It’s a touching moment of closeness and a testament to Bowery’s rarely-noted virtuosity as a physical performer. The dancer Les Child praises ‘those very feminine hands and those brilliantly arched feet.’ Tilley notes that Bowery practised hard for the synchronised dance at the end of Atlas’ later film Hail the New Puritan until he was ‘step perfect’.

Bowery described himself in a 1985 interview with LAM as ‘a sort of cabaret act – the original vaudeville drunkard’, and there are also elements of the English tradition of panto in his appearance as the back end of a horse as well as a teapot in Because We Must. A programme in the Michael Clark & Company press archives at Tate Britain shows the company performing at His Majesty’s Theatre in Clark’s Scottish hometown of Aberdeen in a season that spans Scottish Ballet’s Carmen, a variety show featuring percussionist Evelyn Glennie, a local amateur production of Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, and Dick Whittington. In an unpublished interview shortly before his death, Bowery said that he would like to die ‘by firing squad on stage at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane.’

Bowery’s high kicks are exhilarating because they smash through social niceties to reveal sex and death beneath. An installation at Tate by Jeffrey Hinton includes home movie footage in which Bowery, capering on the roof of his apartment building, goes into a full-length pratfall. Press shots of Because We Must similarly show him stretched out full-length on his side on stage. Tom Sutcliffe wrote in the Guardian that ‘Clark’s style of disco-ballet is all about steps and groundwork. His dancers fall: they aren’t held high. Groups seethe and roll like jam in a saucepan away from and towards the floor.’ Photographs by Dave Swindells capture Bowery, Clark and others prone or prostrate on the floor at Jungle and Circus, club nights that pre-dated Taboo, often entwined and snogging in same-sex couples, a provocation in a deeply homophobic era.

‘For Bowery, dance was how a star shines’

Dance falls and kicks and spills across spaces, from council flat to the dancefloor to the street to the lock-up, and on to the stage, studio and screen: why? Because we must. Bowery and his crowd are making their mark and their point(e) in the face of hostility and, as the 1980s went on, an epidemic of both HIV and silence. One of the most moving exhibits at the Tate comes courtesy of Susanne Bartsch, the fashion spotter who in the early 1980s brought Bowery’s baroque-n-roll designs, including a leather jacket tinglingly fringed with thousands of kirby grips, to New York. At the end of the decade, in 1989, she invited him back to host the Love Ball AIDS benefit at Roseland, filmed by scene documenter Nelson Sullivan. It’s a rare moving-image glimpse of Bowery performing not for the camera, but community.

Video grants us a vivid sense of Bowery’s artistry as a dancer, his incredible awareness of his body in relation to the audience and the lens. Film, that kinetic razzle-dazzle, was a key source of inspiration, particularly his fandom of John Waters and Divine. He ‘put me in mind of Ginger Rogers in Gold Diggers of 1933,’ observes Als of Bowery’s performance at drag festival Wigstock 1993, the year before his death at just 33. Writing in Violette Editions’ Leigh Bowery book, Clark notes ‘we often said that some of what we did wouldn’t be shocking if it were in a film; it’s only because it’s in dance that it’s shocking.’ Watch for the gleam in Bowery’s look to camera as, dressed as the silver star from atop the Christmas tree, he picks up and eats a miniature Clark at the end of Because We Must. For Bowery, dance was how a star shines.

So Mayer is a writer, publisher, bookseller, organiser and film curator. Their first collection of short stories Truth and Dare is out now from Cipher Press.