‘I’ve trained with the RAD since I was four – so taking part in The Fonteyn feels like a nice circle.’ Valentino Zucchetti’s ballet career is studded with RAD landmarks. Now an established soloist and increasingly ambitious choreographer at the Royal Ballet, the Italian’s RAD roots remain strong. The former gold medallist in the Genée International Ballet Competition is now the first guest choreographer in its new incarnation as The Fonteyn.

Zucchetti currently sports a devilishly trim goatee – a sign, he grimaces, of the injury he’s carrying, as he must be clean-shaven on stage. His eyes glint, but can’t suppress the thrumming frustration of recovery. He’s a sharp, candid interviewee.

A perfect fit for the RAD flagship (as RAD Artistic Director Gerard Charles points out, ‘there’s even a studio in RAD Italy’s summer school named after him!’), Zucchetti notched up all the RAD exams from Pre-Primary to the Solo Seal, and won his gold medal in 2006, when the Genée was held in Hong Kong. ‘I have hugely fond memories,’ he recalls. ‘At La Scala Ballet School, we weren’t allowed to do competitions. It was one of the reasons I left. So when I came to the Royal Ballet School, the first thing I did was spearhead into competitions.’

Some events felt ruthless, but the Genée, he says, ‘was a different experience altogether, more nurturing – it didn’t feel like a cutthroat competition, more like a summer course that ended with a performance.’ He relished creating work with guest choreographer Yuri Ng, and being coached by Christopher Hampson (now Artistic Director of Scottish Ballet). ‘It was definitely one of the best experiences I’ve had.’

‘I had no idea I was going to win,’ he says now. ‘There were a couple of dancers that were just killer.’ On stage, Zucchetti was ‘dazzling,’ reported Olivia Swift for Dance Gazette. ‘Compared to longer-limbed male finalists, the 18 year-old is small. Yet he is also strong, controlled, and above all, devastatingly charismatic.’ The gold medal, predicted Swift, would be ‘the start of so much more.’

Zucchetti made good on the prediction, dancing in Oslo and Zurich, and for the past 13 years with the Royal Ballet. Now a First Soloist, he’s notable in roles with dash: Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet, Lensky in Onegin or Puck in The Dream. Alongside, since winning the Ursula Moreton Choreographic Award at the Royal Ballet School, he’s made regular pieces for the Royal Ballet’s Draft Works and increasingly for the main stage – Anemoi returns next year.

Choreographers at the Genée formerly made male and female solos, which all candidates would learn. This time, everyone participates in a single group piece. ‘Solos were great for the first group that got created on,’ Gerard Charles explains, ‘but each subsequent group was basically taught what was already set.’ At his first Genée, in Toronto, choreographer Gioconda Barbuto initially worked on material with all the candidates: ‘but although 70 dancers learned it, only the finalists got to perform it on stage.’

‘This time,’ he continues, ‘I thought it would be great if the choreographer made a piece everybody could be in. They may not be a finalist, but they will still dance at the finals, they won’t be forgotten.’ An ensemble work also gives a taste of ‘creating as a group. No one will know who will be a finalist when the choreography is set, so they’ll all be featured equally. Part of this event is to give people experiences – making this together will be a very exciting experience.’ Zucchetti seemed ‘perfect’ for this commission: ‘he understands young people. He will challenge them. They’ll learn what it is like not to be spoon fed.’

‘I’m looking to make sure the dancers are all involved. It must be challenging, but not impossible’

Valentino Zucchetti

When we speak, applications for The Fonteyn are still open, so Zucchetti has no idea how large a cast he’ll have. Is he planning for 40 dancers, he wonders, or 90? Creating a big number will be demanding, ‘because we are asking a lot in very little time. I’m looking to display the dancers, to make sure they’re all involved. I will try my best while creating to make it educative, so they learn as much as possible. I have to make it challenging, but not impossible.’

It sounds daunting, but ‘I’m quite used to thinking on my feet,’ he says. ‘I use limitations almost as an exercise. I started my craft at the Royal Ballet School, but mostly in the main company, when time is non-existent. I’ve learned to structure rehearsals well, with no time-wasting.’ He hasn’t yet selected music for The Fonteyn: ‘it will be exciting music for sure. I spend a ridiculous amount of time researching music and have a playlist of about 400 tracks ready to choreograph. Music is never the problem.’

Having been there himself, how would he advise the candidates? ‘The ballet landscape has become very acrobatic, but the way to stand out is combining your technique with an innate, natural sense of performing. By all means, show us what you’ve got technically – but the judges have seen it all. They want to see you perform, demonstrating that you could be a valuable member of a company. It’s often in the way you respond to music, new choreography, or to teachers in class – things which to a young dancer might feel marginal are actually key.’

As a choreographer, Zucchetti has showcased ballet stars: Prima (2022) was made for Royal Ballet principals, including former Genée medallist Francesca Hayward. But he also responds to eager youngsters – evident in Anemoi (2021). Named for the Greek gods of the winds, its breezy ensemble moves in gusts and swoops. Big companies, he feels, can keep dancers in their place, but Anemoi was made especially for the corps de ballet. ‘They understood how special that was. That’s why they went all guns blazing, because they were like, this is our chance.’

He enjoys ensemble creations? ‘One hundred percent. Great scores require great structure: the bigger the orchestra, the bigger the cast, and there’s so much you can do within it. My focus is on constantly shifting structure while surfing the musical phrasing. That’s what I like, and what I appreciate in other choreographers.’

I sense a restless itch to create dance. ‘I’m a very hyperactive person,’ Zucchetti confirms. ‘A workaholic, constantly grinding to create more. I think my itch started when I first choreographed, at 16.’ As a dancer he has also watched many other choreographers at work. ‘I have been so lucky, I’ve worked on a ridiculous amount of new creations. Ultimately, each choreographer has their own style. Ideas come from different people or places, and the way you manifest those is very individual.’

He believes ‘everything in my career as a dancer has benefited me, in one way or another. Even bad experiences taught me a lot. You learn how to help a choreographer – I can sense when a choreographer is stuck, and the last thing you want is a sassy dancer looking at you like: what’s next? I gravitate towards dancers with musicality or enthusiasm, or a palpable sense of appreciation for my work. If they’re enjoying it, I’m enjoying it.’

‘I was 35 in May, so definitely heading towards the sunset of my dancing career,’ he adds. ‘I’m so fortunate that I have this other passion. It has limitless growth – as a dancer, all I can do is try to last as long as I can, but I can keep improving as a choreographer until I die.’

‘I gravitate towards dancers with enthusiasm. If they’re enjoying it, I’m enjoying it’

Valentino Zucchetti

He keeps an eye on older dancing colleagues, to see ‘how they exit and how they feel about it. For some people, ballet is all they have – they throw themselves heart and soul into it and can’t see an alternative. Psychologically that can be very difficult. I definitely don’t want to find myself psychologically unprepared when the day comes.’

Finally, why does choreography appeal to Zucchetti? ‘It’s actually very basic,’ he says. ‘Whenever an idea is in my head, it keeps bouncing like a ray of light inside a room of mirrors. One pleasure is the relief of transferring it out of my head. I remember watching something I made for the Royal Ballet School, and I was like, eight months ago this was in my head and now it’s at the Royal Opera House. Genuinely amazing.’

He also loves ‘seeing dancers really engaging with my work. Let me tell you, as a dancer you dance a hell of a lot of things you don’t fully enjoy. But when a dancer’s fully with you, and you see them on stage genuinely feeling the piece – that’s great. And for me, it’s all about what the audience feels. I get such a kick every time.’

Watch

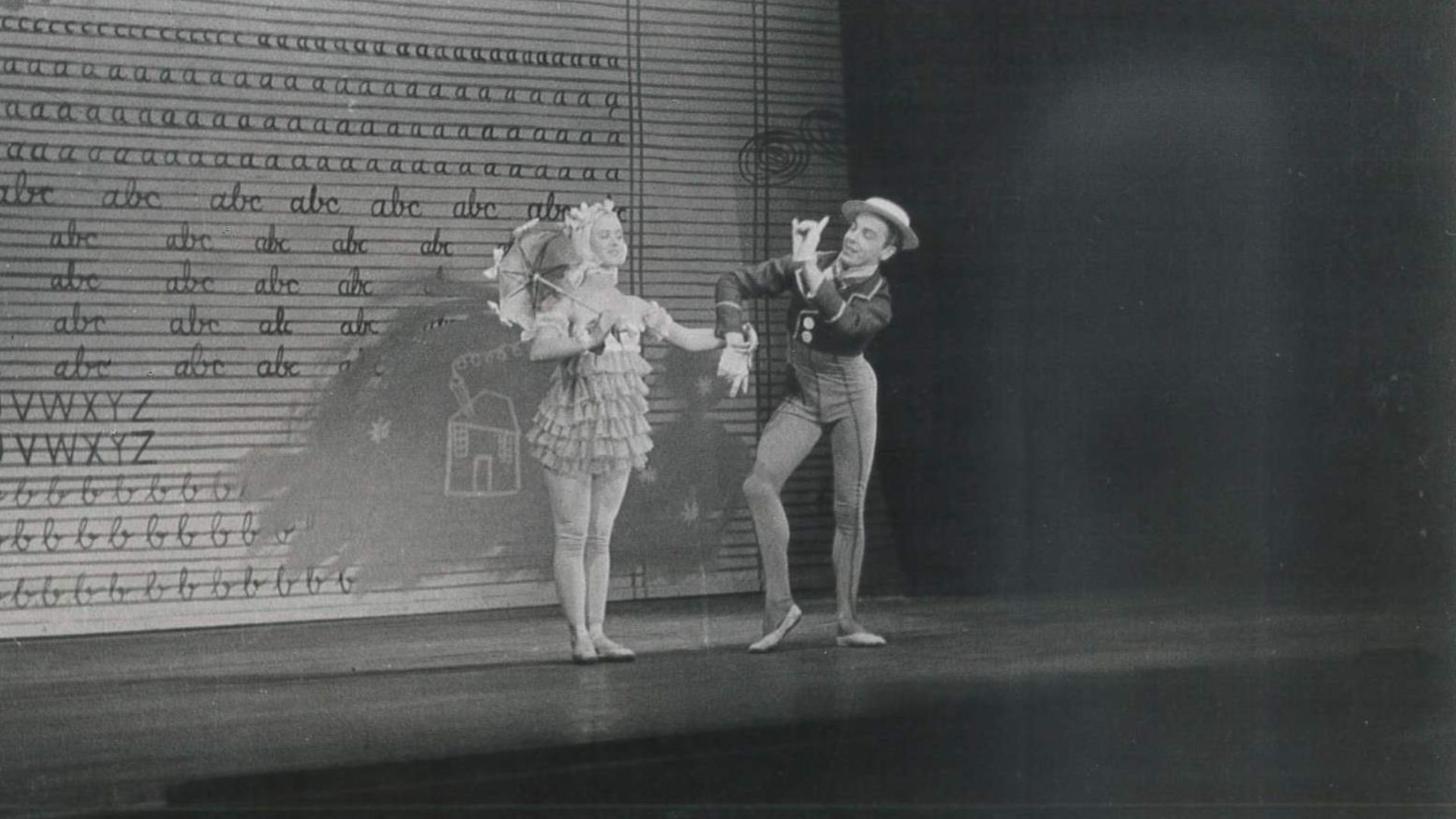

Dancers from the Royal Ballet in Valentino Zucchetti’s Scherzo

What’s new at The Fonteyn?

As The Fonteyn returns in person for the first time since 2019, Gerard Charles, the RAD’s Artistic Director, explains some exciting changes.

Dancers Own

The choreographic prize will now be only for dancers who choreograph their own piece, and not for a teacher or guest choreographer. Our intent was always to encourage young people to choreograph themselves. We offer support from two teachers at the Rambert school. They have made some helpful videos, and will give feedback to the first 20 candidates to send us videos of their choreography, with plenty of time to act on the advice.

Extra events

We’re expanding things out so people beyond The Fonteyn candidates can benefit. It’s not confined to the lucky few. At a series of workshops, community students will have a chance to work with our coaches and learn some repertoire. We’re also running the Phyllis Bedells Bursary in tandem with The Fonteyn, bringing together the paths through the different bursaries the RAD offers, like stepping stones showing where they can lead.

Scholarships

Very few dancers win a Fonteyn medal, but other interesting candidates deserve an opportunity to be seen. For the first time, we’ve negotiated with leading dance schools around the world to offer scholarship positions for candidates who fit what they’re looking for. They include: American Ballet Theatre’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School, Dutch National Ballet School, Royal Ballet School, Canada’s National Ballet School, New Zealand School of Dance, North Carolina School of the Arts, Rambert School and Queensland Ballet Academy among others.

Join the Fonteyn audience at the final (booking is exclusively open for RAD Members until 30 June)