‘What is it like to perform in a big immersive piece?’ Since joining Punchdrunk’s latest production The Burnt City at the tail end of 2022, I’ve been asked this question more times than I can count. Yet each time, I’ve struggled to find a satisfying answer that encapsulates the scale of the work and summarises the breadth of my experiences.

To the uninitiated, as writer Jonathan Mandell describes it, immersive theatre is a form of theatre that ‘creates a physical environment that differs from a traditional theatre where audiences sit in seats and watch a show unfurl on a proscenium stage.’ Mandell suggests that immersive theatre tends to engage all five senses through site-specific and participatory means, promotes each audience member’s experience as tailored and unique, doubles as an art installation and focuses on a well-told narrative. Felix Barrett, Artistic Director of Punchdrunk, prefers the term ‘site sympathetic’ for their productions which disrupt form, challenge audiences and blur the line between reality and fiction.

‘Could I fit into this way of working and let go of the safety of the fourth wall?’

Isaac Ouro-Gnao

I was completely unaware of the immersive world when I heard word of an audition in summer 2022. A good friend, actor Milton Lopes, was already playing a variety of roles in The Burnt City and put my name forward. After being called back, I watched the production, paying extra attention to the characters I would portray – host of a bar in the Trojan underworld, and Askalaphos, a flower shop owner, spy and aide to Hades, god of the underworld. To truly explain what it is like to perform in the work, I must tangle with what it was to witness what fans describe as ‘a sensory masterpiece.’

Inspired by the events around the fall of Troy, The Burnt City transports Greek tragedies into two unassuming warehouses in Woolwich, south London. The performance occurs over three hours, with one-hour loops that repeat and thread different stories and characters together. Crucially, audience members curate their own experience, following the sights and sounds that most intrigue them. The neon streets of Troy and the militant walls of Mycenae are enveloping and disorientating; sounds flutter through each wall, while lights dance from menacing to calming, reflecting the bodies moving through each space.

I watched each character, surrounded by audiences in Punchdrunk’s trademark white masks, and imagined their perspectives. What did they see of the show? How are performances affected by such proximity? And could I fit into this way of working, letting go of the safety of the fourth wall? These questions formed as I witnessed this turbulent, beautiful, overwhelming and enticing world, ready for Maxine Doyle, choreographer and co-director of the production.

‘I was very much thinking from the beginning: ‘Where are the audience? What are they seeing? What are the sightlines?’ says Doyle, when I recently sat with her over Zoom. ‘We need to be able to create work that exists from many points of view. I’ve always loved dance up close, ever since I saw an early work by Phoenix Dance Theatre when I was 14, a duet in the Blue Coat Chambers in Liverpool. It was just two male dancers in a tiny venue – they were right in front of me and so physical, beautiful, athletic. I really felt the kinetics of that.’ But it isn’t just what proximity passively creates between audience and performer, but also how the performer then takes ownership of that proximity, making choices that are right for character and narrative.

‘On a big stage you can lose small details, but in a Punchdrunk work, they scream very loudly’

Maxine Doyle

‘I enjoy not dumbing down the physicality because of proximity,’ Doyle says. ‘If anything, you can turn it up as long as you are safe. On a big stage, theatrically and choreographically, you can sometimes lose those small details, whereas in a Punchdrunk work, those details can scream very loudly.’

To master such details, Doyle employs a choreographic practice translated through the language of cinematography. The notion of audience members as camera lenses shifted my perspective going into the resident role of Askalaphos. Those farther away could be seen as wide-angle frames and those up-front as close-ups. Those at the side have the frame of a side profile while those crouching down have a low angle. How can I convey my character’s emotions from all angles? All these perspectives might seem overwhelming but the focus of detail and specificity dispels anxiety.

It’s here that the richness lies. As Doyle says, ‘I realised that having a text as a starting point means we can turn the abstraction down. We need naturalistic movement, from rhythm, tempo, partnering and contact.’ To perform a work like The Burnt City is to refine movement and physicality – from expression to body language – to convey a specific story.

For Omagbitse Omagbemi, a skilled and experienced performer who has worked with Punchdrunk since 2009, and played Clytemnestra, queen of the Greeks in The Burnt City, this pursuit of refinement was borne from yearning for more from the US dance world. She found Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More in New York, which reimagines Shakespeare’s tragedy of Macbeth. ‘I knew nothing about immersive and what it entailed,’ she adds. ‘It’s nerve-racking of course, when you’re used to the audience being [seated in a proscenium] and then all of a sudden, they’re around you. But that also makes it exciting because you have to dive into that film aspect of the lens.’

Mallory Gracenin, a New York-based actor and performer who joined Sleep No More’s cast in 2011 and also performed in The Burnt City, takes a similar approach. ‘Your performance can vary depending on how close they are to you,’ she says. ‘If I’m simply interested in a piece of paper, actively reading and engaging in it, the audience will lean into that and do the same thing. If I need to see something, they will see it too.’ Doyle encourages this symbiosis of performer and audience ‘because for the audience peering over your shoulder, those moments are thrilling.’

My first experience of surrendering to The Burnt City was quite the thrill. Yuwei Jing found the same at Sleep No More in Shanghai in 2016: ‘I thought, “wow, that can be theatre!”’ Jing had loved acting since high school, but, unable to train professionally, she took gigs in children’s drama. ‘As the demand for multiskilled performers grew,’ she continues, ‘I decided to restart my acting career, specifically for immersive theatre.’ This led to work with the likes of Ontroerend Goed, the Belgian theatre company whose production £¥€$ (Lies) came to Shanghai in 2019.

‘You can’t fake anything. You’re so close to the audience’

Yuwei Jing

Set up like a casino, £¥€$ (Lies) navigates the intricacies of the economic world. Each table, led by a croupier, represents a country with currency represented by poker chips, while each audience member is a bank. Jing played a croupier, with dialogues navigating the 2008 financial crash. She learned gestures of dealing chips, like a hand choreography with fixed rhythm and tempo. ‘We had to remember all the specific vocabulary of the finance industry and say the lines like muscle memory,’ she says. ‘You can’t fake anything. You’re so close to the audience so you need to be real.’

This is the naturalistic movement Doyle speaks of – Omagbemi summarises it as ‘it’s important to be the person as opposed to trying to convince the audience you are that person’. Ontroerend Goed’s artistic director Alexander Devriendt centres this approach in the company’s practice: ‘I don’t ask you to pretend. Everything we do is truthful. That’s the beauty of this.’ His work is rooted in real-world events and issues and Ontroerend Goed invites the audience to remain who they are. In the 2008 production Once And For All, 13 teenagers ‘stop and they look at you for 10 seconds, telling you ‘You are here. We know you’re looking at this. Look at us. It’s okay.’’

That freedom and permission to see and be seen has been thrilling in my first immersive experience. To arrive at Devriendt’s ‘truth’ is no easy task. It involves shedding expectations from experience of the proscenium; expectations of how audiences will behave and where their focus will be. In my first performance, the anxiety of the audience’s proximity was very present. But Doyle and the rehearsal directors give us answers to put into practice. To view an encroaching audience member as not a threat or nuisance but a curious lens to work with and reward. To use touch to create a safe distance when proximity becomes dangerous. To hone the senses inwards and control my words and actions to convey a story. To invite the audience into our world which then also becomes theirs.

Most rewarding of all is the real time audience feedback. In The Burnt City, which closed in September, I got to witness the audience physically react and emote. The masks they wear are still quite revealing after all. Are they lively or quiet? Forward or reserved? This affected my choices, in how I highlight details or the lenses I’m more attuned to. No two performances were the same.

So, what is it like to perform in a big immersive piece? ‘I feel like a constant beginner and I’m still passionate about understanding and learning,’ says Omagbemi. ‘But I appreciate being able to dive into the work and into myself. I find it exciting that we can all get lost in the world – though as performers we also have to be present with how we navigate it.’ Gracenin concludes that it feels like bestowing a little magic. ‘The beauty of the work for both performers and audience is that for a few hours, we escape to a new world,’ she says. ‘I like watching and believing that the imaginary can be true for a while.’

WATCH

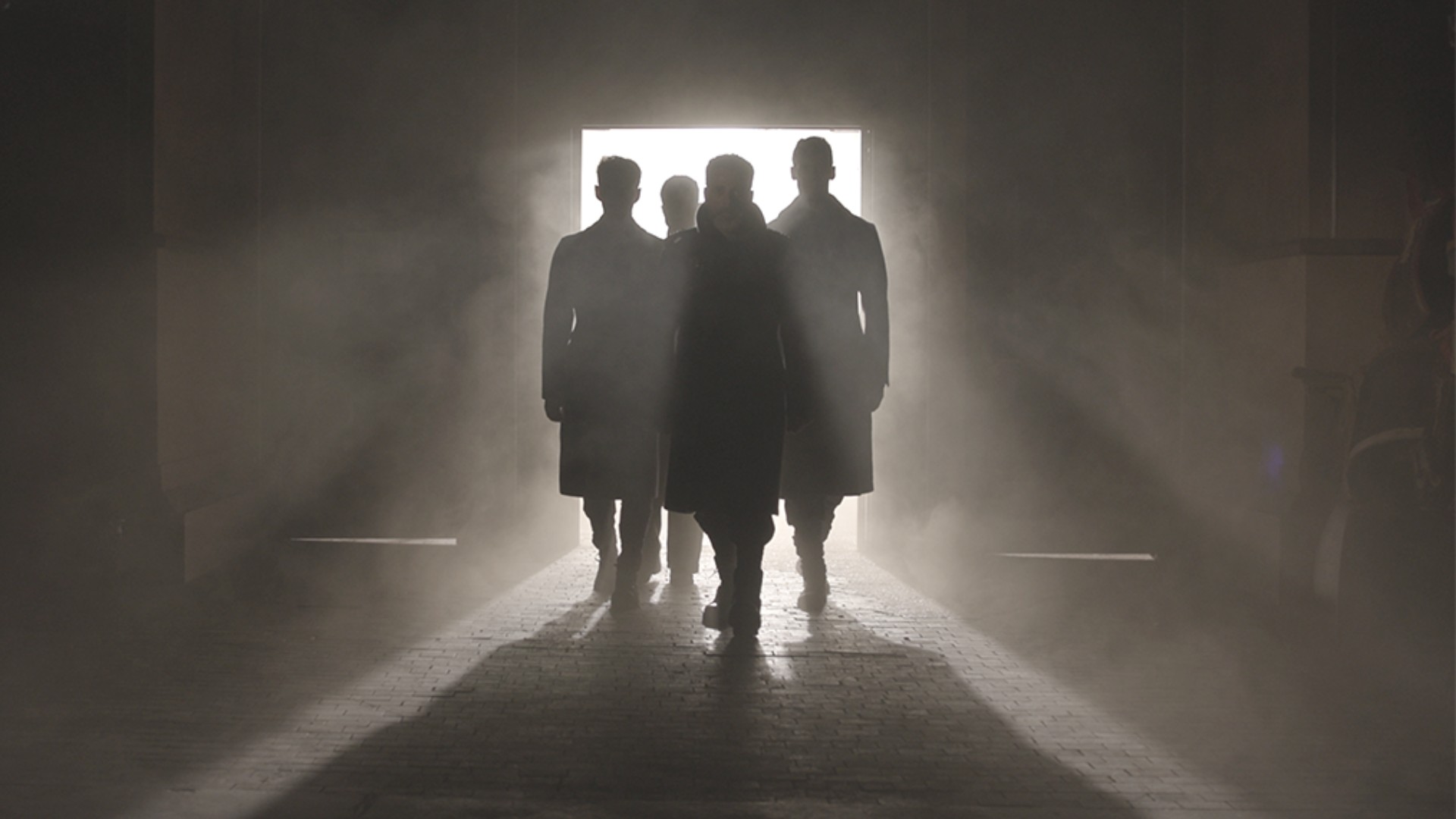

Trailer for The Burnt City

Isaac Ouro-Gnao is a Togolese-British

multidisciplinary artist and freelance journalist.