The air was electric in the Aud Jebsen Studio Theatre this past November as the audience took their seats for the annual Bedells Bursary competition. Alexander Campbell, Royal Academy of Dance Artistic Director, welcomed them to the intimate studio theatre and introduced judges Dame Monica Mason, a Vice President of the RAD, and choreographer Ashley Page. Finally, he announced the young competitors, who ran in with cool composure, forming one long line across the back of the stage.

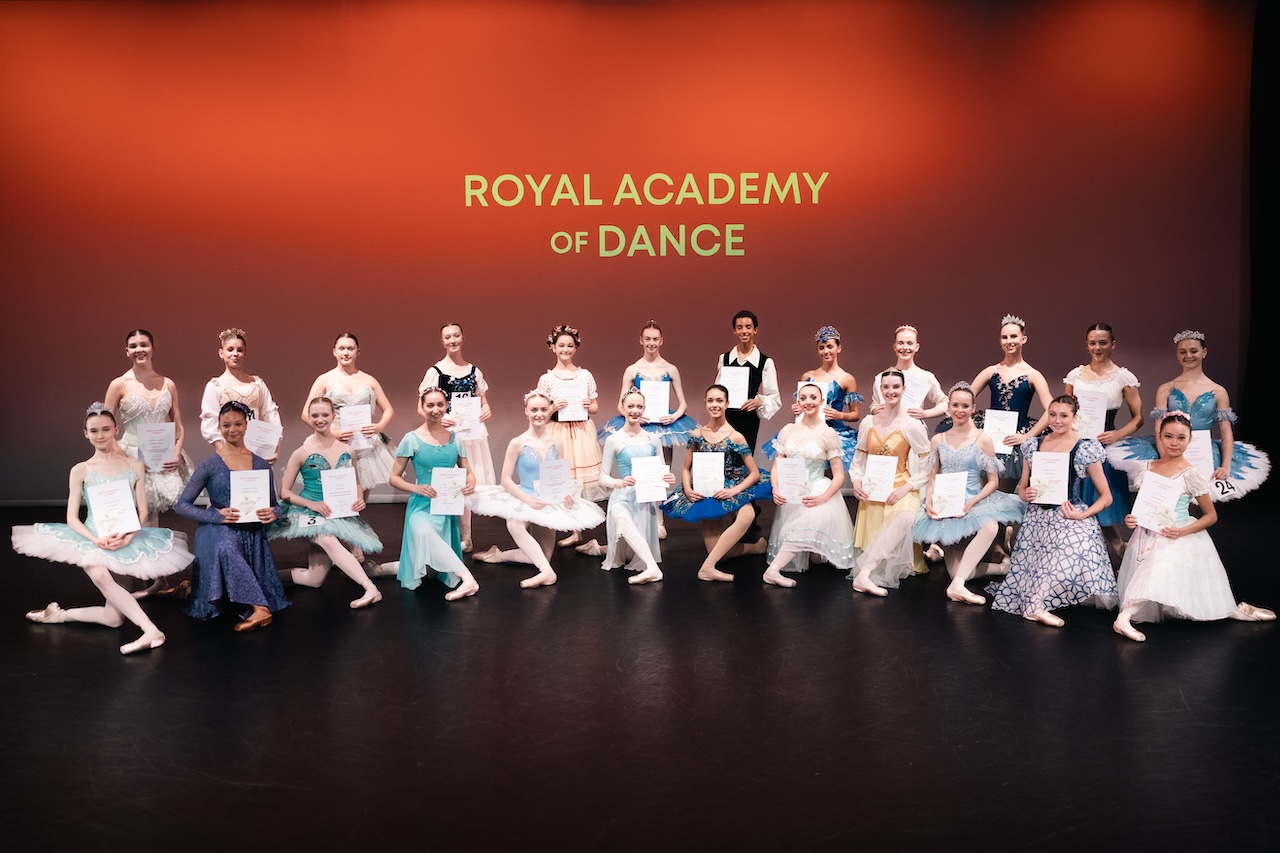

The 24 talented hopefuls, aged 14-17, attended the Bedells Bursary at the RAD’s award-winning headquarters. Named for Phyllis Bedells, a celebrated dancer and a founder of the RAD, the competition’s 51 previous winners include principal dancers Lauren Cuthbertson and Anna Rose O’Sullivan of the Royal Ballet and Joseph Caley of the Australian Ballet.

‘It’s very interesting to see the dancers’ personalities,’ says Campbell afterwards. ‘There’s a lot that goes into making a dancer and a lot of opportunities to display your strengths. Some people had the ability to surprise you with their classical variation or their Dancer’s Own work. You can’t always pick it [in class]. At The Fonteyn and again at the Bedells, some people excelled in different areas that weren’t immediately obvious based on how they set up at the barre or do a tendu.’

‘It’s interesting to see the dancers’ personalities – some people surprise you’

Alexander Campbell

‘I was very shocked and happy. I couldn’t stop smiling’

Lucy Crawford

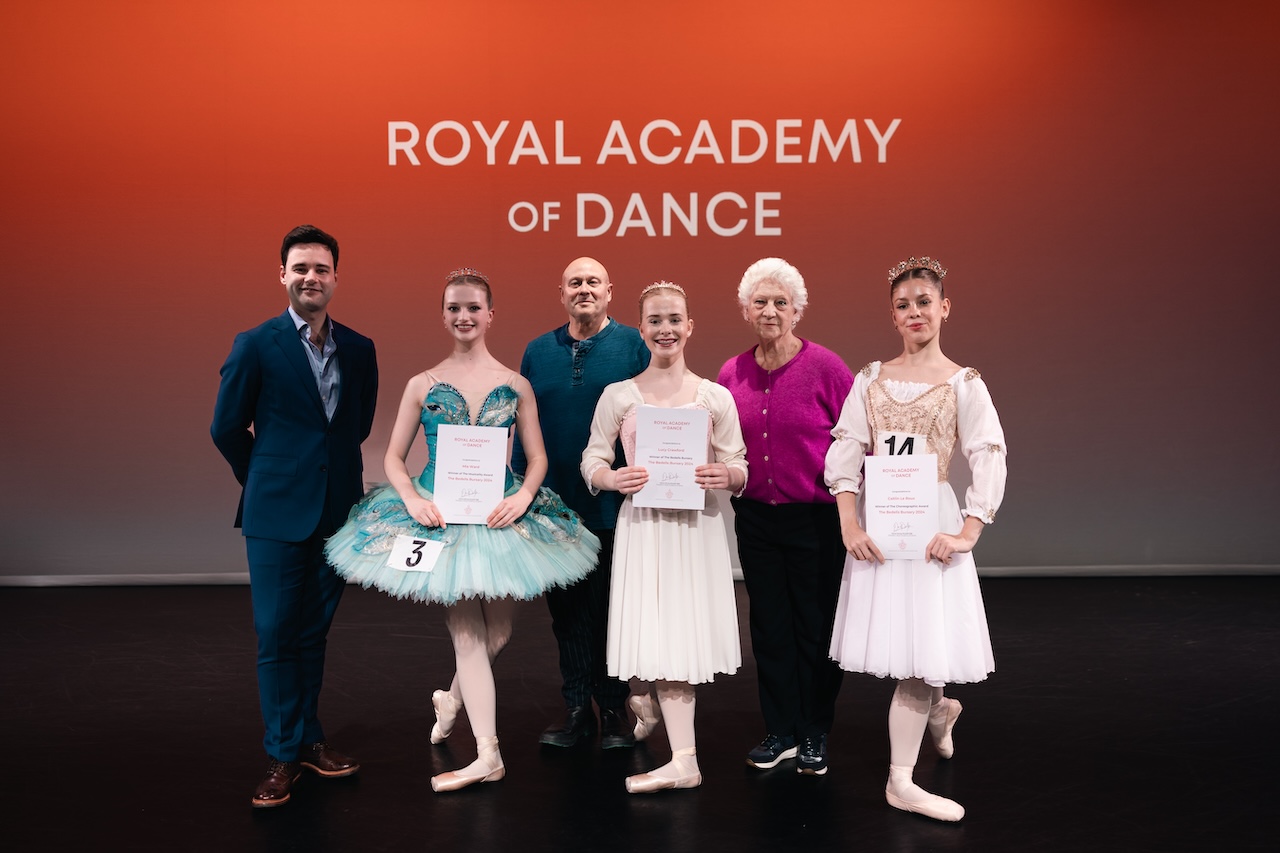

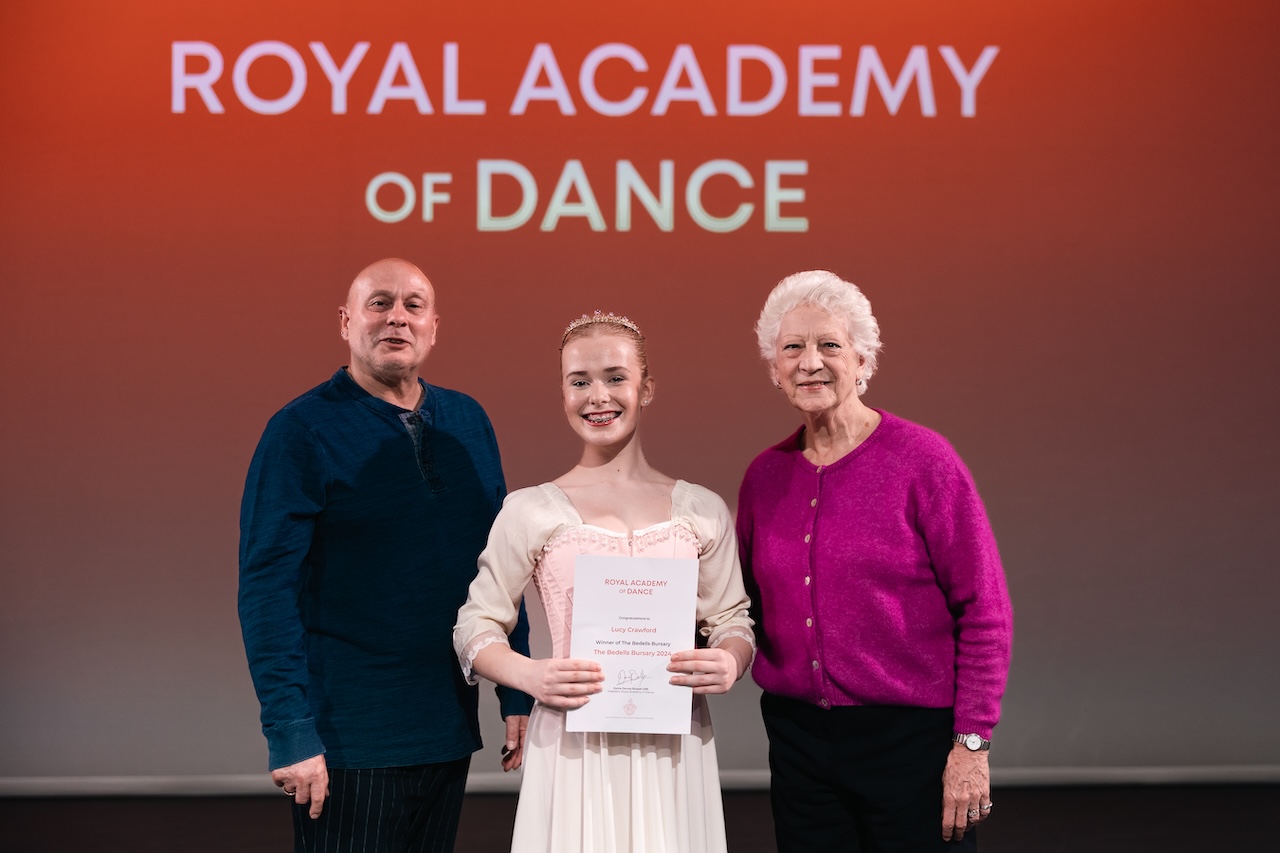

This year marks 45 years since the first Bedells in 1979, with 15-year-old Lucy Crawford (who trains at Elmhurst Ballet School) becoming the 52nd winner, funded by the Mary Kipps bequest. With her confident technique, bright-eyed focus and long lines (accentuated by a vibrant teal leotard in class), her poise and evocative performances stood out. ‘I was very shocked and very happy. I couldn’t stop smiling,’ she recalls a few weeks later. Her mother, Louise Crawford, bursts with pride: ‘to watch Lucy perform at such a high-level competition was really good. It was worth every little bit of cramp in my right leg every time I was driving up and down the motorway,’ she adds with a laugh.

Caitlin Le Roux, 16, from Tring Park School for the Performing Arts, won the Dancer’s Own Choreographic Award of £250 (funded by the late Dr Ivor Guest’s estate) for her piece Running from Time. 21 candidates choreographed variations for this award; Crawford’s entry, Contemplation, was a heartfelt tribute to her grandfather. ‘The music I used is Remember Me by Chris Mann, a song dedicated to Alzheimer’s Disease. My granddad had Alzheimer’s, so I choreographed and performed it for him. It was like looking into a mirror, trying to remember yourself and the emotions you feel when you don’t know who you are.’ Having honed her skills in Elmhurst’s choreography classes and also independently, the result was an evocative homage to her grandfather.

The inaugural Musicality Award of £100 was won by 15-year-old Mia Ward (Mayhew School of Dance). Funded by the Lynn Wallis Bursary Fund, this was introduced to recognise and promote musicality. Campbell believes that, although they are interconnected, emphasising the importance of musicality along with technique is vital. ‘I’ve had instances where I’m watching a performance and because of the way that the person’s moved, I’ve heard things in the music I hadn’t noticed before,’ he says. ‘We have that power as dancers, which is incredible – if you can harness that, it elevates what the art form can be.’

Presenting the award, Dame Monica Mason remarked that musicality goes beyond just dancing on the beat. ‘You immerse yourself in the music so that it makes you listen differently. You don’t just hear it – you listen keenly. You use that musical sensitivity to inform the audience – a very musical dancer is able to illustrate the music for the audience.’

Following Dancer’s Own, the candidates returned to perform classical solos, accompanied by pianists Jacob Krokodeilos and Martin Cleave. Darren Parish had coached these the previous day, offering final notes to accentuate the solos. The traditionally female variations were from The Sleeping Beauty (Princess Florine, Act III), Coppélia (Swanhilda, Act I) and Swan Lake (first female variation from the pas de trois). The traditionally male variation was from the Act I peasant pas de deux in Giselle. Each dancer brought their unique interpretation and energy to the variations.

‘I very much enjoyed seeing the differences in all three disciplines,’ says Campbell (candidates were assessed on a technique class, as well as the Dancer’s Own and classical variations). ‘You get quite an interesting perspective on each of the candidates.’ Mason emphasises that ‘the basics need to be practised every single time you have a lesson, every single time you dance, so that by the time you come to do the classical variation, you’re not trying to disguise any weaknesses. You actually face the weaknesses – you play to the strengths, but also don’t bury the weaknesses.’

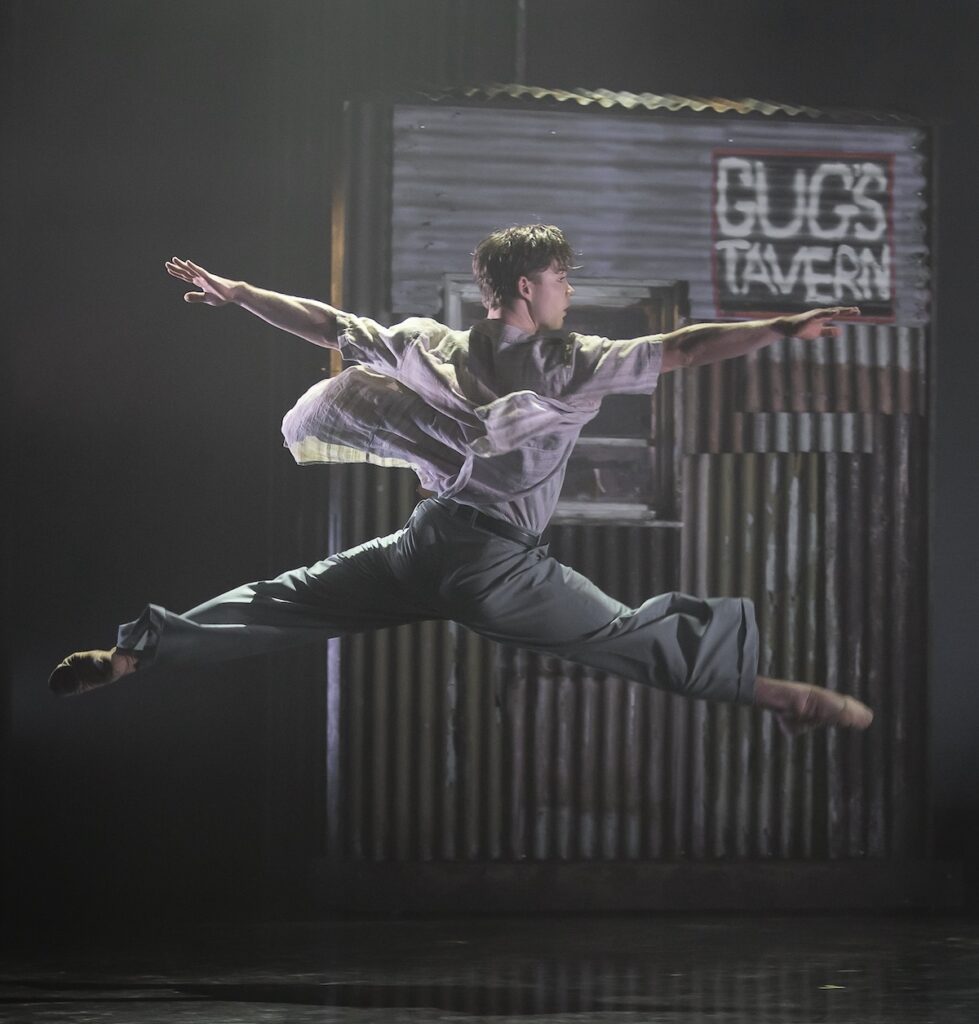

For many, the Bedells is a pathway to the RAD’s flagship event, The Margot Fonteyn International Ballet Competition (formerly the Genée), providing a strong foundation for young dancers’ futures. Now a Northern Ballet junior soloist, Harris Beattie won both competitions nearly 10 years ago: the Bedells in 2015 and the Fonteyn in 2017. He describes the RAD competition as ‘a positive, nurturing environment that brings out the best in the dancer – to strive for excellence, not perfection.’

Beattie reflects on the challenges that ultimately made him a stronger person and dancer. ‘I first did the Genée in 2015 and didn’t get through to the final. Obviously, I was upset and I considered it a failure,’ he says. He then reframed his mindset, seeing his experience not as a failure but a growth opportunity. Two years of training later, he became the first person to win all three awards at the Genée: Gold Medal, Choreographic and Audience Choice Awards. ‘It’s the support from the people around you and your teachers that can scaffold you and help you with those difficult moments,’ he explains. ‘As a dancer you can get stuck in your head – it’s being confident enough to let that go and know the work that you’ve done leading up to [the competition] will be in place, and to enjoy the day.’

‘The RAD competition is like a family, you get to know people really well’

Harris Beattie

‘The RAD competition is like a family,’ Beattie adds, ‘you get to know people really well.’ Campbell, too, competed in the Genée, winning silver in 2003. ‘I always think about the people I met and have kept in contact with to this very day, who I probably wouldn’t have had the opportunity to be friends with otherwise,’ he reflects. ‘Having the perspective of doing it some 20 years ago and it very much being a catalyst for the career that I then enjoyed, and even for my current role – I look at [the candidates] and think, there’s so much opportunity ahead of you.’

Now, Crawford prepares for her upper school auditions and her Advanced 2 exams. She too plans to compete in the Fonteyn and join a ballet company. Her mum says that the prize money is ‘burning a hole in her pocket,’ but will be used in part to fund her training. Louise excitedly describes a big picture frame she hung with the Bedells programme, photos of Lucy with the judges and her winning certificate. ‘It’s up on the wall in pride of place,’ she says. And to future competitors, she advises, ‘try your best, but enjoy it and absorb the whole experience because it was just lovely, from both a parent’s point of view and for Lucy as well.’

Catja Christensen is a writer and dance scholar from Virginia, USA. Currently based inLondon, she earned an MRes from the University of Roehampton as a Fulbright Scholar. She has written for PointeMagazine, OOF Magazine, thINKingDANCE and The Oslo Desk, and also works for Gold Standard Arts Foundation.