Music is so much more than just the loudest aspect of a ballet performance. Music tells us how to feel, cutting through all of our walls and hitting us in our soft and vulnerable insides. Sometimes we have feelings that are just too big, that we can’t put into words, so we rely on music.

Music is also crucial to great storytelling. Without music, beloved classical ballets would amount to nothing more than dancers in nice costumes running around to the sound of their own heavy breathing and pointe shoes. Depending on the choreography, the music can be the best part of a dance performance. George Balanchine himself once said ‘if you don’t like ballet, you can always close your eyes and listen to the music.’

Even if you can’t see them, music is embedded with cultural signifiers. Hundreds of years ago, European composers made up what they thought music from other cultures might sound like, based on little pieces of information or descriptions but no authentic aural exposure. They used reeds and cymbals for ‘Arabian’ music, pentatonic scales for ‘Chinese.’ Asymmetrical rhythms. Unusual percussion. They broke traditional rules so as to be ‘exotic,’ seeking to create music that sounded like it came from somewhere else – fantasy places where anything might happen. And so began hundreds of years of music being part of reinforcing certain fantasy places and characters in ballet, opera and more.

The problem with these inaccurate, stereotypical or caricatured depictions today is that European fantasy impressions from hundreds of years ago can now feel authentic when they’re actually not. Today’s audiences are diverse, and no one wants to see their culture flattened, distorted or exoticised. We who love ‘Western’ classical arts find ourselves at a crossroads. We have a rich repertory of lovely music and dance made by European artists hundreds of years ago. Powerful work that speaks profoundly to the human condition and contains sublime music. But some are a little bit (or a lot) racially and/or culturally problematic today. What do we do?

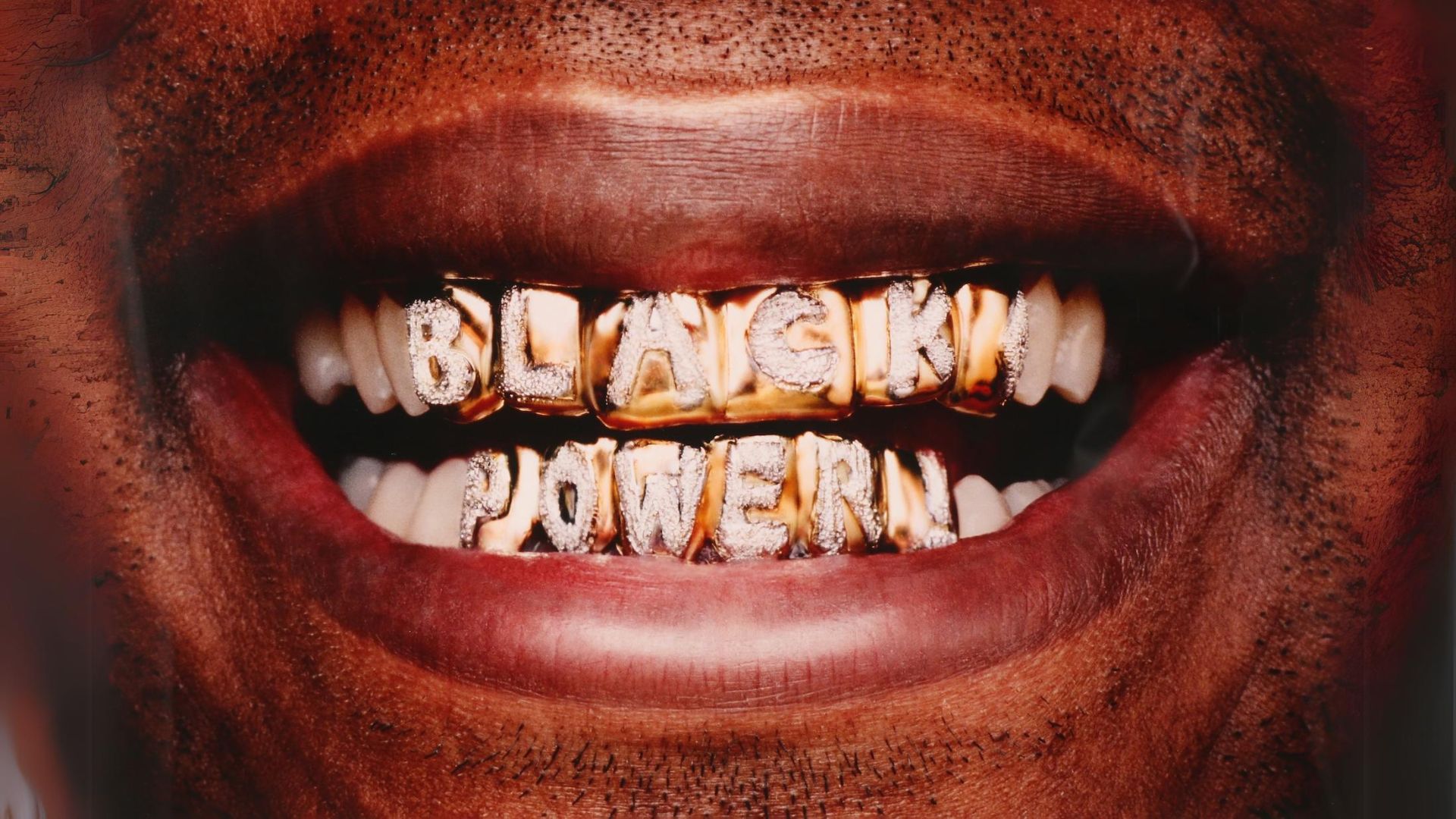

‘No one wants to see their culture flattened, distorted or exoticised’

Phil Chan

‘A prompt that guides my creative decision making is: “What else could it be?

Untangling these thorny issues has become a staple of my creative work as a writer, choreographer and opera director. Can we save works from angry demands to ‘cancel’ them, and instead reimagine them for today’s diverse audiences so that everyone can feel included? A prompt that guides nearly all of my creative decision making is ‘What else could it be?’

Answering this question involves a few others:

What is the work? We distil a work down to what it’s about at heart, and ask what has to remain to keep it recognisably ‘itself.’

What is ‘the problem’ with it? This may involve listening to someone who has a different perspective or lived experience than we do. This is one of the hardest parts of the process (and perhaps, of being human), but without such openness, we can’t really imagine and play with other options.

What was the social context of the work when it was made, and what is different about the social context now? Nerds rejoice! To understand the social, and maybe political, conditions under which a work was created, a firm grasp of history is required.

What was its intended impact? Why was something funny 200 years ago? What context was this story critiquing when it premiered? If you want an old piece to move people alive today, you need to figure out why it ‘worked’ in the first place.

Why is it worth reviving? Does the work speak to this moment in a unique or sublime way? The vast majority of performing arts works aren’t ever revived, and that’s okay. Not everything has to be performed again, unless there is a compelling and urgent reason.

Now that we’re warmed up, let’s consider how we can reimagine music that is ‘Oriental’ in theme, a European fantasy of Asia as opposed to a cultural product from Asia. Oriental music doesn’t necessarily have to relate to a specific story or narrative; sometimes it’s simply meant to evoke an exotic perfume. ‘The Chinese dance’ in The Nutcracker is a great example. The best prescription is to create something else that accompanies the music – something so resonant that any unsavoury ‘Oriental’ associations are knocked out. In this way the music no longer functions as an inaccurate cultural signifier.

When we want to keep the music, and perhaps the choreography, while replacing offensive cultural caricatures, we could invite Asian artists to reinterpret scenes, making them authentically Asian. Another choice is to craft new scenarios that have nothing to do with Asian culture or are abstract. Disney’s Fantasia is a great example of reinterpreting ballet music. Ponchielli could never have imagined that his Dance of the Hours could be interpreted as terpsichorean crocodiles, hippopotamuses and ostriches, or Stravinsky that his riotous Rite of Spring could also be a prehistoric dinosaur bacchanal. These cartoons take nothing away from their balletic origins, but instead expand the potential for appreciating the music.

Fantasia also illustrates what happens when we fall back on stale stereotypes instead of charting new creative ways forward. Where Fantasia fails is when it regurgitates tired Chinese and Arabian tropes in its ‘Nutcracker’ suite: the harem girl goldfish and coolie-capped mushrooms with slits for eyes. Imagine if Disney had asked ‘what else could it be?’ when animating those sections!

What about Orientalist music that accompanies a specific narrative? How do we apply ‘what else could it be?’ to a work such as Turandot or Le Corsaire? How do we shift a work from being Eurocentric – by and for European people who lived over 100 years ago – to one that resonates with today’s audiences? In my experience, the first step is abstracting their essence. When we boil a story down to its most basic parts, we’re forced to confront what the piece is actually about. Upon this distilled version we can layer new elements to create a congruent story – add texture and detail fitting the new dynamic we’re trying to create. In the process we may discover nuances and implications we hadn’t grasped before.

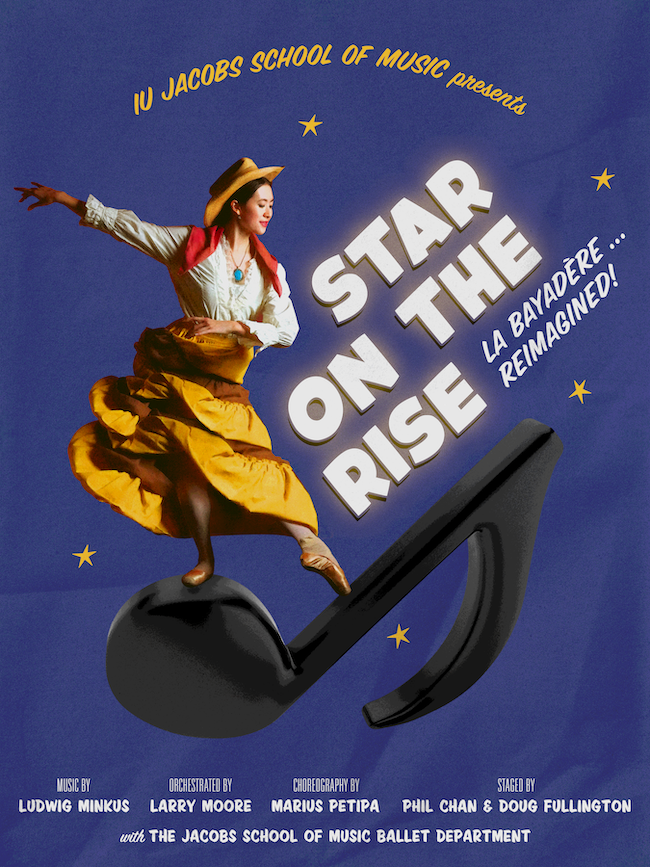

My next big project uses this approach: it’s a restaging of the full La Bayadère for Indiana University, set to premiere in March. La Bayadère done in a traditional manner usually involves inaccurate and offensive depictions of Hinduism and Buddhism, Blackface and the license to project ideas onto a fantasy Indian setting that might not have any authentic Indian cultural integrity. Here, I’m working alongside the brilliant Doug Fullington, a musicologist and dance notation expert, to restore Petipa’s notated choreography, in a reimagined story that takes place in the 1920s during the Golden Age of Hollywood musicals. We have handed over the Minkus score to Larry Moore, a musical expert on the period, who has rearranged the ‘exotic’ music into a glittering jazz-age musical.

Reimagining orchestral music is easier than taking on music with words. Opera lyrics add a layer of specific meaning – changing stories and settings becomes much more complicated. I discovered this first hand while directing a new production of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly for Boston Lyric Opera this past September. My mandate was to keep the beautiful music while addressing the many problems with how the opera has been traditionally staged, especially the portrayals of Asian women. Are stories about geishas being victimised really the best narratives to repeat over and over?

‘Beloved classics continue to speak to us as long as we are willing to imagine something that works for us now’

What followed was a year-long investigation called ‘The Butterfly Process’ that identified the issues with traditional stagings of the opera (available on Boston Lyric Opera’s website). As a result I was asked to direct the opera, reimagining the setting in the 1940s in California. The story revolved around a Japanese jazz singer who pretended to be Chinese because of anti-Japanese sentiment following the bombing of Pearl Harbor during WWII. (‘Geisha’ in Japanese means ‘artist,’ so reimagining Butterfly as a jazz singer is an appropriate answer to ‘what else could it be?’)

We wanted to keep Puccini’s sublime music, and as many of the original lyrics as we could, but in order to do so we sometimes found ourselves assigning or addressing familiar lines to different characters, or letting them have different meanings within the new context. The response has been positive, with traditionalists relieved that we haven’t modified Puccini’s music, and Asian audiences thrilled that Japanese characters haven’t been reduced to caricatures.

Ultimately, beloved classics – warts and all – can continue to speak to us as long as we have an openness to play, to listening, to reflecting, and then a willingness to imagine something that works better for us now. Sensitivity to this process will both serve the art of the past while resonating with a wider audience today. Doesn’t that sound better?

Phil Chan is a choreographer, director, advocate, and the President of the Gold Standard Arts Foundation. His books include Final Bow for Yellowface and Banishing Orientalism.

Sinjin Li is the artist name of Welsh-Chinese illustrator and designer Sing Yun Lee.