Adeline Genée was a prima ballerina, a founding member of the Royal Academy of Dance (and its first President) and a Dame Commander of the British Empire. Yet she has never received the recognition she deserves as a world class dancer and key protagonist in the creation of a British ballet culture. Why might this be? What made Genée so remarkable and who is the woman behind the porcelain princess?

Born Anina Jensen in Aarhus, Denmark in 1878, Genée began her dance training with her uncle, Alexandre, and made her debut in Oslo at the age of ten. It is worth noting that the bulk of Genée’s performing career was spent in the music hall, a form of light entertainment popular throughout Britain in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Music hall (or palace of varieties) offered an evening’s entertainment comprising a series of ‘acts’ with a Grand Ballet as the main attraction. London’s two most famous venues, the Alhambra and the Empire Theatre, were both located in Leicester Square and attracted huge audiences across a diverse social spectrum. Genée enjoyed a ten-year reign (from 1897 to 1907) as première danseuse at the Empire, an unprecedented achievement which won her consistent critical acclaim and a host of admirers.

Genée refused Diaghilev’s offer to join the Ballets Russes, preferring to appear at the Empire alongside jugglers and performing pets

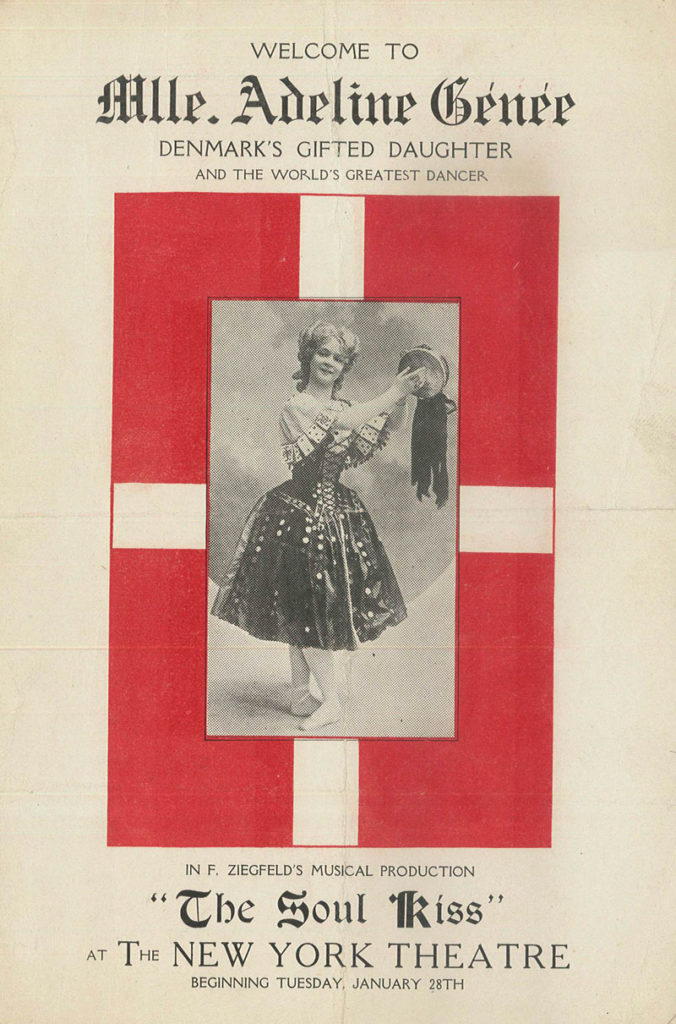

Genée performed in ballets created by Kati Lanner (resident teacher and choreographer at the Empire) as well as creating works in collaboration with her uncle, gaining high praise for Les Papillons (1900), High Jinks (1904) and Cinderella (1906). Other London performances included La Camargo (1912) and the very first British performance of Coppélia (1912) at the Coliseum. She undertook regular tours of the US, billed as ‘the world’s greatest dancer’, making her American debut in Ziegfield’s The Soul Kiss in 1908. She subsequently toured Australia and New Zealand, before returning to the Coliseum for her last major performances in London as The Pretty Prentice (1916).

This brief summary cannot do Genée’s career justice but it is worth highlighting the sheer volume of work involved. The music hall was not repertory theatre with seasons and breaks in between; the doors at the Empire opened all year round. In addition, Genée could not alternate with a second or third cast: her devoted audiences would not accept anyone else. Similarly, on tour, Genée would give hundreds of performances, many of them solo, with the highest expectations from management and audiences alike. Performing night after night as the star attraction (and without the benefit of today’s dance science and supplementary training regimes) must have taken an immense amount of dedication, discipline and stamina – not to mention a clean, assured technique which minimised wear and tear or career-threatening injury.

We might find it shocking that Genée refused Diaghilev’s offer to join the Ballets Russes, turning down the opportunity to join an illustrious group of creative artists who achieved mythological status. Fokine might have created a new role for her – she could have danced in Les Sylphides or Petrouchka or choreographed her own ballet to a newly commissioned score from Ravel or Debussy. But she did none of those things – preferring to remain at the Empire where she was regularly billed alongside jugglers, contortionists, comedians and performing pets!

We could argue that Genée, like Anna Pavlova, preferred to be the only star in the firmament and/or that her contract was more lucrative than Diaghilev’s ad hoc financial backing. I think it more likely that she understood the significance of her preferred milieu in preparing British audiences for an indigenous ballet culture. The Ballets Russes London seasons were seen by an elite few – Genée’s audiences were vast by comparison.

Genée with Alexander Volinine in Les Sylphides. Photo: Dover Street Studios

Genée in A Dream of Butterflies and Roses. Photo: Hugh Cecil

Comparisons with Pavlova are significant in that the two dancers were contemporaries. As noted in Alexandra Carter’s pioneering study Dance and Dancers in the Victorian and Edwardian Music Hall, Pavlova received legendary status whilst Genée’s achievements have remained largely unsung. Many of us would associate the bourrée on pointe with Pavlova in Fokine’s The Dying Swan and yet, according to Ninette de Valois, it was Genée ‘whose prowess in this classic movement will probably never be equalled.’

Part of the reason for Genée’s relative invisibility is the lowly status accorded to the music hall by a generation of ballet critics and historians. For many, it lacked respectability. Derogatory remarks are exemplified in Nicholas Bentley’s Ballet-Hoo (1937) in which he describes ‘a debauch only to be excused by the grace and intelligence of Madame Genée.’ Another possible factor is Genée’s preference for elaborate (and rather uncomfortable looking) Edwardian-style costumes which gave her a doll-like appearance (hence the frequent references to Dresden china and porcelain). No romantic ballet tutu or sylphide wings; neither do we see the shorter classical tutu of the Imperial Russian ballet classics and the extension of limbs which it reveals. If you placed an image of Genée between one of Marie Taglioni (circa 1832) and a young Alicia Markova (circa 1932) it would look incongruous and yet it is Genée and the music hall ballet that provides the crucial link in British ballet from one century to the next.

Publicity for Genée’s season in New York, 1908

Programme design by Edmund Dulac for Genée’s performance at a gala in 1932.

Photo: RAD Archive

Under Genée, the RAD gained an international network, a vastly increased membership and status as a centre of excellence

Watch

Darcey Bussell sees Adeline Genée’s ballet shoes and celebrates her work at

On Point: Royal Academy of Dance at 100 at the V&A.

Whatever her status in the ballerina hall of fame, few have made such a significant contribution to the teaching of ballet. As the RAD’s first President (from 1920-54), Genée displayed a whole new skill set and was surely one of the first women in Britain to earn the title ‘Madam President’. Her success in gaining first Queen Mary as patron (1928) and then a Royal Charter (1935) are evidence of both her professional reputation and social mobility. In her 35 years as President, Genée initiated numerous projects (including a syllabus framework, the Genée Gold Medal Awards, a teacher training course and even Dance Gazette), managed the ambitions of colleagues, and challenged the prevailing tradition of dancing masters and male expertise. Under her reign, the Academy gained an international network, a vastly increased membership and national status as a centre of excellence. Genée was also a founding member of the Camargo Society, which helped launch both Ballet Rambert and the Vic-Wells Ballet.

In 1950, Genée was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire, the first person in British theatre dance to receive such high recognition. In preparation for her retirement, she made an astute choice of successor, helping de Valois to persuade Margot Fonteyn to take on the role. Genée died in 1970 at the age of 92, part of a generation that survived two world wars and a Spanish flu pandemic. All of which suggests a steely determination: less a porcelain princess, and more of an iron lady.

Carol Martin is a freelance dance lecturer, writer and historian with a special interest in gender and identity in British ballet.