‘Looking back, I’m not sure how I did it!’ laughs Samantha Clark. ‘But I did – and it worked.’

Samantha Clark, known as Sammy, a mother of two boys, runs the Central Scotland School of Ballet with her sister Amanda Clark, whose own son has just turned four. The pair took over the school from its founder, their mother Jacqueline Clark. It is, in every sense, a family business. Sammy’s children joined her in the studio while she taught from when they were, respectively, six and three months old. Once big enough, they had their own little play area and tended to be remarkably self-sufficient – apart from a few times when, as an enthusiastic toddler with a walker, one would try to join in with the dancers. Similarly, Amanda’s child, who was born during the Covid pandemic, sat at the side of classes once in-person teaching resumed or was strapped to her chest when she covered classes.

Although the Clarks are aware of a culture among some dance teachers which sees bringing your baby to work as ‘unprofessional’, they felt insulated from those attitudes by running their own school and the friendly atmosphere that prevailed. Sammy mentions how other parents would offer to take the baby for a walk while she taught their children and how the seniors enjoyed the responsibility of pitching in with the little one. Choreographing nappy changes to class changeovers, providing ample snacks and managing occasional meltdowns were some of the relatable stumbling blocks, along with rapid-onset illnesses. ‘I have had it once where one of mine’s thrown up in class,’ recalls Samantha with admirable stoicism. ‘It’s one of those things and you have to just stick a chair over it…’

Vomiting bugs and filled nappies aside, dance teachers face issues that make combining professional life with raising children especially difficult. I spoke to teachers based in Scotland, Hong Kong, Germany and Switzerland and all raised the issue of working hours. Dance classes typically happen in the late afternoon and evening, making them incompatible with nursery and school operating hours. Childcare arrangements are tricky and can mean missing seeing their child for the entire day and only returning home once they’re in bed. Weekend working hours and commitments such as summer showcases – as Jamil Tsang, a RAD teacher in Hong Kong, pointed out – are additional challenges.

So how do they do it? One common solution is for a child to take lessons at the same school where their parent teaches – or to just camp out doing homework in the changing rooms. Fabiana Maltarolli, who runs the Zurich Ballet and Contemporary Academy, made space for doing homework in the school’s waiting room. She has a son who took lessons from age six to nine, before moving on to playing the piano and manning the buffet at school performances. Now aged 19, he is complementing learning Business Studies with an internship in the school’s own admin department. ‘He is happy to work in the family business,’ Maltarolli reflects. ‘He’s learning a lot and feels very inspired.’

‘It’s not good to go along your whole life feeling guilty’

Carla Duggan

Other, less practical, hurdles faced by dance teachers with children will be familiar to many working mothers of all professions. Carla Duggan, who heads the Dance Connection in Stirling and Callander and has two daughters, spoke of the ‘guilt’ that can occur. ‘With dance teachers, it’s more than a job for a lot of us and I think you’re going to feel guilt for not being at your dance studio, and then your children come along and you feel guilty for not being with your children. So [the question is] how you manage that, because it’s not good if you go along your whole life feeling guilty.’

This aspect of what is popularly termed ‘mum guilt’ was echoed by Lisa Dirkx, who runs the dance school Hey Hilde in Nuremburg. Dirkx says she copes with the ‘emotional’ challenge of feeling like she’s either not dedicating enough to the business or not being present enough with family by continually reminding herself: ‘I’m doing my best in both roles.’

Dirkx also mentions the volume of ‘behind-the-scenes tasks like managing bookings, planning classes and maintaining the studio’ which further invade family time. The workload of many teachers, especially those also running businesses and managing staff, is formidable. Combine this with the additional ‘mental load’ mothers often already carry and you’ve got very limited headspace and time for any kind of downtime.

Similarly, top-down societal factors which impact on dance teachers are shared by some mothers doing other jobs, including state maternity provision (or lack thereof) for the self-employed. There’s also a strong gendered dimension to the conversations I have and the topic of dance teacher-parents generally. The RAD workforce is 95% female and the teachers I spoke to are all mothers (although I did try, unsuccessfully, to find a dance teacher father). Maternity pay and leave, plus expectations around whether a mother should work (and how much) and a mother’s own preferences around childcare all contribute to whether teachers-slash-mothers can successfully combine the two sides of their lives.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that many ideas about what would make the work-life struggle easier reach further than dance-specific practicalities (although the subject of working hours is frequently raised). Stefanie Zeh, who runs Go Dance in Tübingen, Germany, and raises two daughters, is well-versed in the mental stresses put on working mothers. She also highlights the roles others around them need to play, including dads who shouldn’t be fawned over simply for doing an equal amount. Along with her husband – who does do 50% – Zeh credits her parents for helping to look after her young children and emphasises the importance of community. ‘With my first daughter I thought: I have to be strong, I have to manage everything. But you need a lot of people around you and you have to learn to ask for help.’ Zeh says. ‘It’s not a bad thing to ask for help as a mother.’

‘You need a lot of people around you and have to learn to ask for help’

Stefanie Zeh

‘Our teachers are very resilient and creative in navigating their way’

Jan Pang

One version of this ‘village’ can come from the female-centric dance teacher workforce. Jan Pang, a mother-of-one and the RAD National Director in Hong Kong, describes her female-dominated workplace as being one where topics from pregnancy and breastfeeding to menopause can be discussed without embarrassment: ‘They always talk about different problems – they like to share!’ Equally, she and many others felt that becoming mothers had made them more empathetic to colleagues with kids and better at teaching children. ‘It’s really helped me, as a business owner and dance teacher, to see things through the eyes of a parent when I’m making decisions at the school,’ shares Duggan who, like Zeh and others, also believes following her passion makes her a positive role model for her daughters.

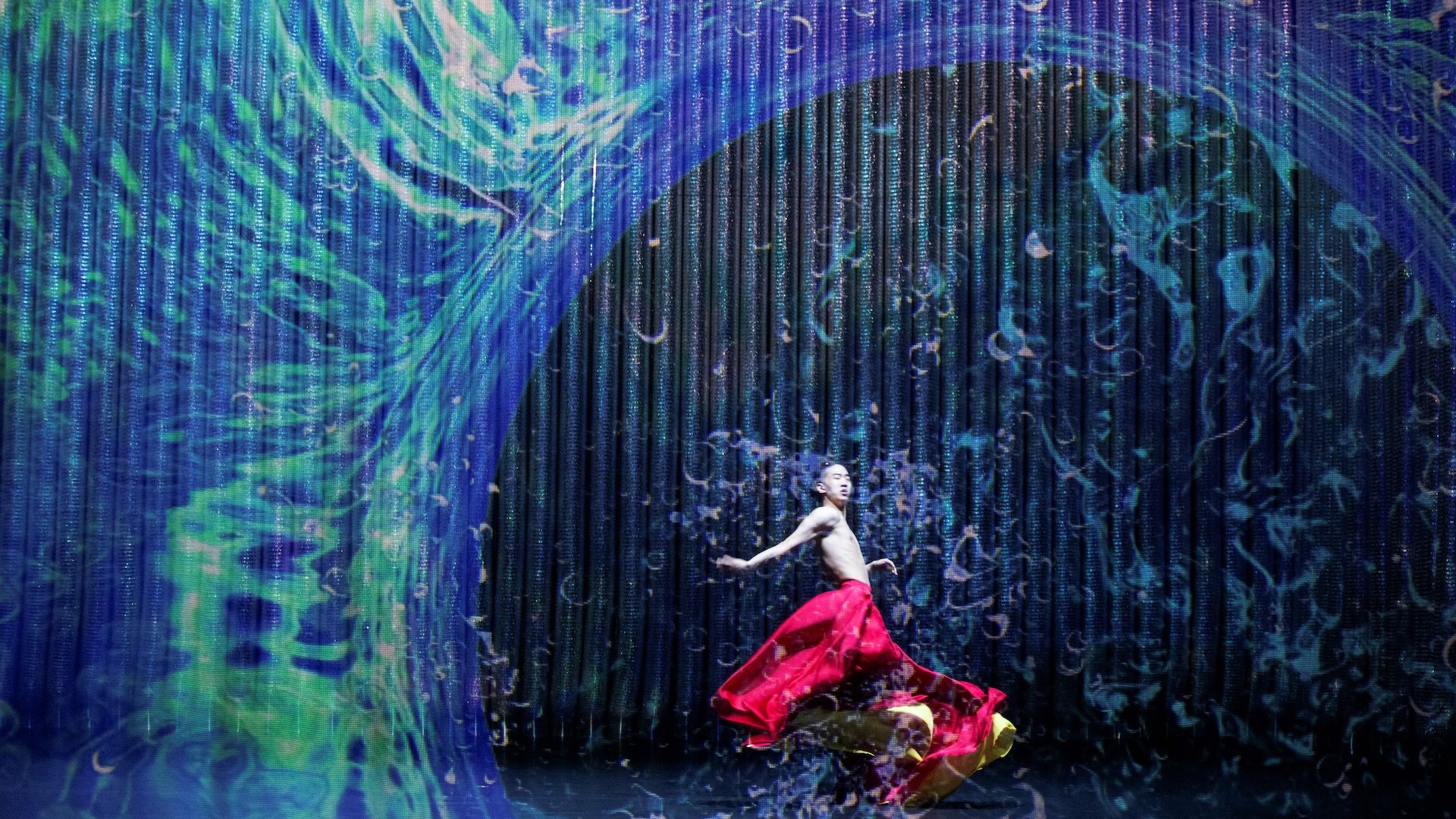

And perhaps dance has some lessons of its own to lend to the home-meets-professional juggle. ‘I can see that our teachers come from dance training,’ says Pang. ‘They’re very resilient and they’re very creative in navigating their way. My impression is that they can do anything: they’re super women.’

Rosemary Waugh is an art critic and journalist for titles including the New Statesman, Time Out and the TLS. Her first book, Running the Room: Interviews with Women Theatre Directors was published in 2023.