‘Honestly, I don’t care about the audience,’ Eun-Me Ahn says bluntly. ‘I do what I have to do. I’m trying to be good as an artist.’ The South Korean choreographer beams through a filter of colourful flowers on our video call – but as a dance maker frequently described as avant-garde, her commitment to her own path is bracing. She strikes out, and audiences must follow. And isn’t it the artist’s job to surprise, even to shock, with something never seen before? How does it feel to be slapped across the cheeks by the unexpected?

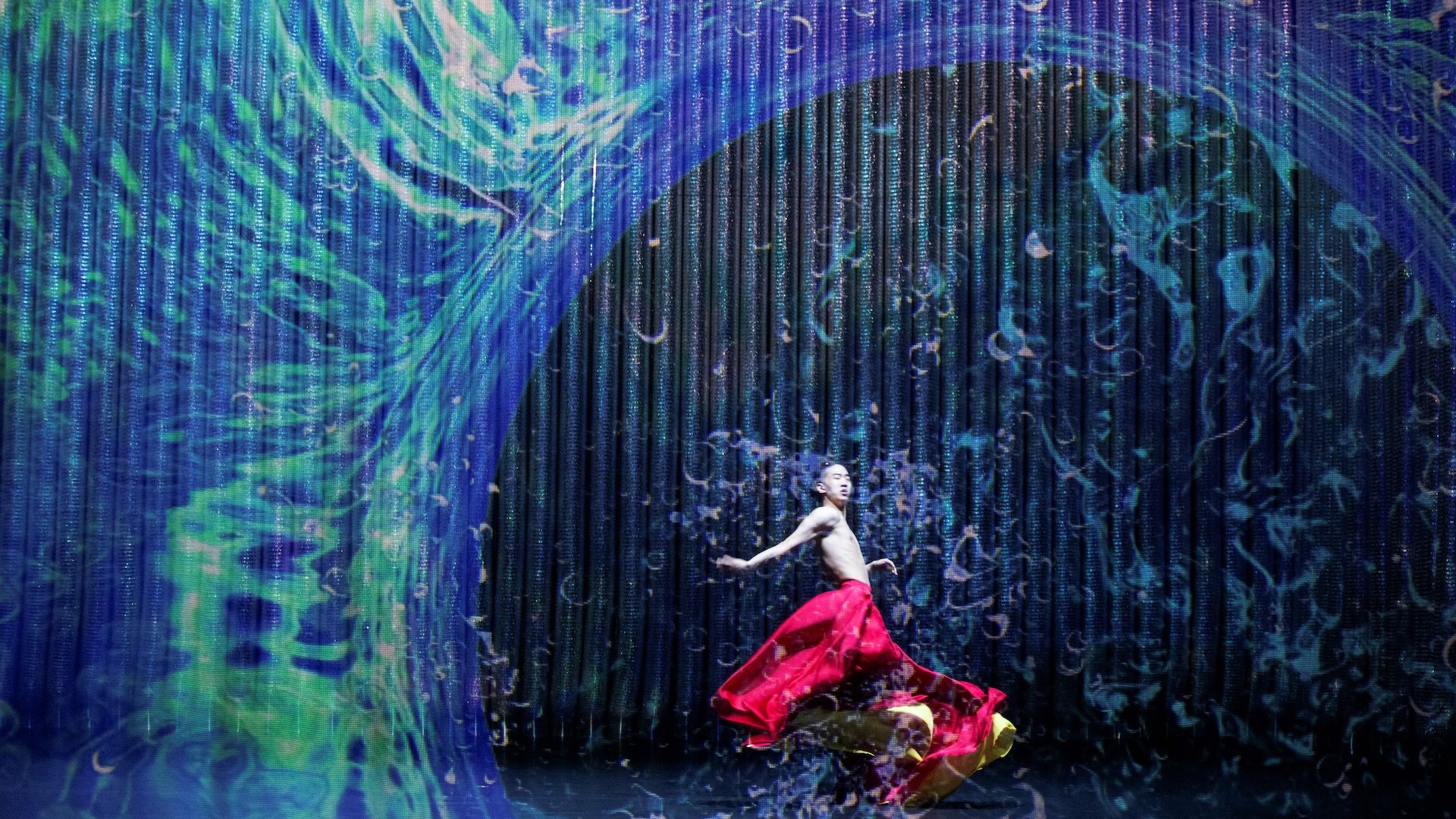

Launching a new work, Ahn says, is like shouting ‘”Ta da! Surprise!” Sometimes people like it, sometimes they don’t understand. But I go on, like a fast runner. That’s why I never get bored.’ Boredom isn’t an option in Ahn’s 2021 show Dragons, a delirious carnival of costume and sound. Now beginning a UK tour, it’s a wild ride. ‘I feel the energy from the audience,’ Ahn says. ‘At the end, they need two seconds to come back to reality. Then they start screaming! When they go crazy, that’s why I’m dancing, to invite them to a place they have never been, so we can have a joyful communication.’

For dance curator Serge Laurent, experiencing an artwork it is more important than rushing to judgement. ‘Unfortunately, most people think that the spectator is passive,’ says Laurent. ‘I believe that to be a spectator is a job, it’s not passive. A trained spectator can deal with complexity, with different, unusual and new things. Sometimes people faced with contemporary dance say, we don’t understand it. I answer, why do you try to understand? When you visit a new place and hear a foreign language you know there is an another way to receive things. So please, if you don’t understand, don’t worry. Be open to receive something you don’t know.’

Laurent is director of dance and cultural programs at Van Cleef & Arpels, curating its Dance Reflections festivals in New York, London and Hong Kong. He sees more dance than most – can he still be taken aback? ‘Sometimes it takes time to appreciate an artistic approach,’ he considers. ‘I don’t come from the dance milieu – I studied ancient art. When I first approached contemporary art, I was curious about how weird it was. The first time I saw a piece by Pina Bausch, it took time to appreciate it. Now I think she’s an incredible artist. Sometimes I see work I don’t appreciate – I won’t give names! – but it’s interesting for me to ask why I don’t like it. It’s a good lesson for daily life.’

‘If you don’t understand, don’t worry. Be open to receive something you don’t know’

Serge Laurent

The curator’s main duty, Laurent says, is ‘to be a mediator between creation and audience. I invite people to an experience. I’m not telling them what they have to like.’ Contemporary artists, he suggests, ‘are inventing vocabularies, inventing their specific voice.’ He mentions French choreographer Rachid Ouramdane, whose gravity-defying Outsider is in Dance Reflections. ‘He trained as a contemporary dancer, then met with people from extreme sports and climbing. Combining these different sources of making movement, he created a very strong vocabulary. It’s really something – I’m curious to see how it will evolve.’

Dance Reflections places startling new work in conversation with modern masterpieces by Trisha Brown or Merce Cunningham. ‘You can connect vocabularies,’ Laurent says. ‘It’s important to talk about people who were in their time very avant garde and who became, one step at a time, quite formal – look at Lucinda Childs.’ Even so, he adds, ‘you can never foresee the reaction of an audience. You put people together in the same room, but no one sees exactly the same thing.’

‘As artists, we are not afforded the luxury of being stingy with our emotions’

Chanel DaSilva

Speaking from New York, the American choreographer Chanel DaSilva describes how she assimilates new dance. ‘I try to sit as a spectator and let the work fall on me. I try not to read the programme notes, or go to the pre-show talk – I want my own experience to guide me.’ One formative inspiration was Ohad Naharin’s Tabula Rasa, seen as a student at Juilliard. ‘I was bawling my eyes out. There was something so raw, unapologetic and visceral. I was like, This is how I want to feel every time I see art, because it makes me feel something new.’

DaSilva has since created work for Joffrey Ballet in Chicago and many more. ‘Some of my most powerful works are rooted in my own real life experiences that I’ve been brave enough to pull out of my heart and put onto the stage,’ she says. What was the first piece that felt like her own voice? ‘It was in 2016. The piece is called Susan, and it’s in honour of my mother. My mom died in 2006 and I did not reckon with that grief. I stuffed it way down deep in my psyche, never to be seen again.’ Her psyche had other ideas. ‘David, I did not want to make that work! I was not ready to deal with the grief, but it kept coming up in my dreams. I could see the opening tableau. And I was like: fine, Mom, I will make the work. And when it finally got to the stage, I could see my signature all over it. It was very clearly me.’

‘With every piece I made, people said: what’s going on here?’

Eun-Me Ahn

It takes courage to make such exposing work, I suggest. ‘As a younger choreographer, I was more guarded,’ DaSilva admits. ‘I wasn’t ready to uproot my experience and share it.’ Now, she recognises discomfort as a sign of substance. Her new piece for Ballet Black is Shadow Work, named for the investigation in therapy of ‘all the emotions, memories, experiences that we’ve suppressed.’ It sounds uncomfortable – but, DaSilva continues, ‘I often tell my students that as artists, we are not afforded the luxury of being stingy with our emotions. As hard as it is, you want to keep all of your experiences – good, bad, the challenges, the angry – right here, underneath the top layer of your skin, so that you can access them.’

Experimental artists often kick against a strait-laced society: Diaghilev in imperial Russia, Pina Bausch in 1970s Germany. Ahn, born in 1963, grew up in a nation still recovering from the Korean war and in thrall to overseas influence. ‘We believed America was the best – King America. But my generation realised, it wasn’t enough about us – it’s fake. We were trying to find out: who am I, what is Korea, what do we need?’

Ahn made her first piece in 1988, a conservative time in South Korea. ‘Even on the street, people would say, look at the crazy person. With every piece I made, people said, what’s going on here? They’d never seen it before. People still don’t understand what I’m doing, but they do respect me, because I never stopped. That’s the artist’s job – no matter what, you have to follow your process and the next step is coming.’

‘For an artist,’ Ahn considers, ‘the hardest thing is that every great artist did everything before you were even born. What are you going to do?’ Her own intimidating inspiration was the great German choreographer Pina Bausch. ‘She was my best friend. But I must get out from under her to be an artist. What can I do that she didn’t? She didn’t know Asia well – okay, this movement and sensibility will be mine. I’m trying to find the beauty that nobody has seen before.’

‘You don’t like to repeat yourself,’ chips in Ahn’s manager, Jean-Marie Chabot. Dragons was followed by Koshigi Monologue, a swerve into the fraught history of South Korean womanhood. ‘It’s not funky like Dragons,’ says Ahn. ‘The reaction is different, more internal. Many women have told me they cried because they feel the sickness and fear.’ Her next production, The Post-Orient Express, promises a further swerve.

DaSilva danced with Trey McIntyre Project for six years (‘Trey’s work was in your body, your mind and your everything’), so is also familiar with the need to escape a creative influence. Achieving her own voice, she says, involved a ‘conscious unlearning,’ Ahn recognises her own influence on young Korean dance makers (‘now everything is colour’), but hopes they will make their own discoveries. ‘It’s good for young people to get out from the old ones, and process new ideas, fresh energy.’

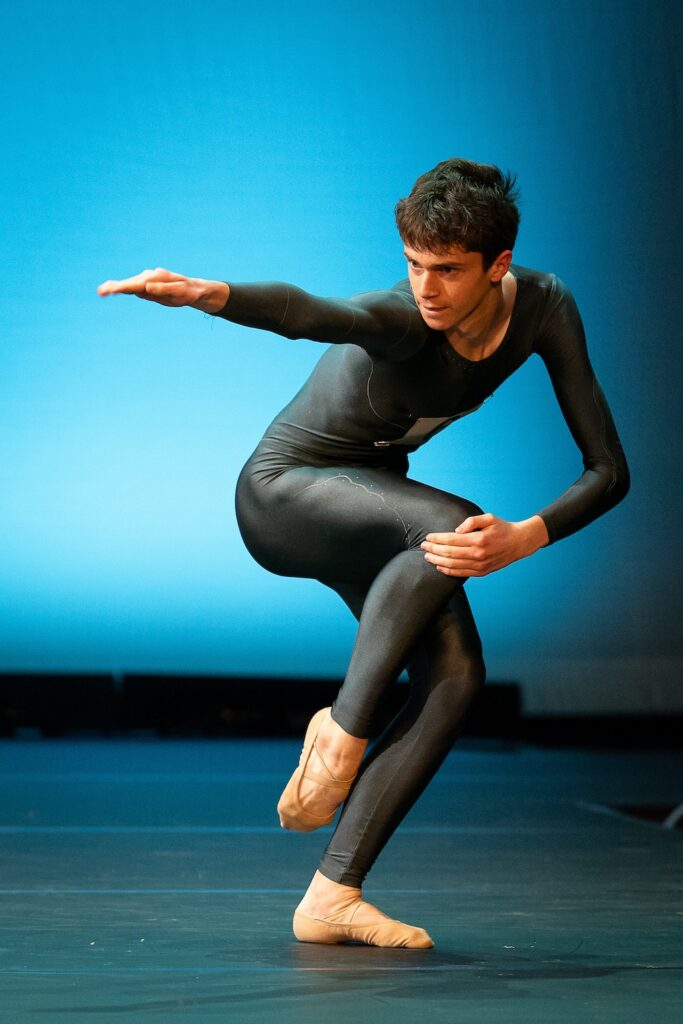

At the beginning of his choreographic career, Ernesto Young, 17, won the Dancer’s Own Choreographic Award at The Fonteyn in 2024. ‘I’ve always loved choreographing,’ says the Australian, now studying at the Berlin State Ballet School. ‘Ever since I can remember, I’ve been choreographing, filming and then choreographing more.’ Whirlwind Grace, his spiky solo set to a fearsome piece of Lutowslawski, was, he says, the first creation that truly felt like his own voice. He had inspirations – including the ‘super mechanical movements’ of William Forsythe’s In the middle, somewhat elevated – but Young also challenged himself to ‘never go with the first movement that comes to my head.’ How does he know when a piece is done? ‘I guess you feel it in your body – it gives you that rush when something connects.’

Over time, avant garde or experimental work may become mainstream. But for DaSilva, ‘art is supposed to challenge us, to make us question things. As a spectator, I love that – please shock me, show me something I ain’t seen before. Please!’

Taken by storm

Ernesto Young explains how he made Whirlwind Grace, his award-winning Fonteyn solo.

A week before the Fonteyn applications closed, I had no intention of applying, as I didn’t get a bursary. At the last minute an arts enthusiast in New Zealand offered the airfare, so I only had three days to prepare.

I was headed to the Fonteyn, but had to find music very quickly. I was inclined towards Max Richter or Philip Glass – it’s a trend right now to go down that emotionally intense dynamic – but my teacher, Archibald McKenzie, wanted music that would take everyone by storm. He showed me Lutowslawski’s Dance Prelude 5, probably the wildest piece I’ve ever heard. It’s impossible to count, it sounds like a circus act. I was like: no way, I’ll make a fool of myself. Then I began listening to it with headphones, hearing the little nuances. It grew on me, and started to brew in my mind.

My brain moves at a million kilometres an hour, which is where I get a lot of my inspiration. I only started full time ballet training last year. I loved jazz and the commercial side of contemporary dance: to hit shapes hard and add personality is what stands out. It took months to bring to life, because it’s such a difficult piece of music.

Whirlwind Grace was the first time I created something that resonated with my style. Winning the Dancer’s Own Choreographic Award meant even more than the bronze medal, and performing at His Majesty’s Theatre was such a rush. It was the peak of my life.

‘My brain moves at a million kilometres an hour’

Ernesto Young

WATCH

Ernesto Young’s Whirlwind Grace at The Fonteyn 2024