It was a dramatic end. John Cranko, the choreographer who transformed Stuttgart Ballet into an ensemble of international standing, asphyxiated on vomit caused by a mild sleeping drug whilst flying back to Germany with his company following a tour of the United States in 1973. He was just 45 years old, and the dance world was left in shock.

‘It was so sudden, you felt you had lost everything,’ remembers Reid Anderson, former Stuttgart Ballet principal and later its director. ‘We didn’t realise what we had until we didn’t have him. It was like a major disaster.’

Five decades on, Cranko is now recalled with reverence and affection. As Mary Clarke wrote in her Dancing Times obituary, he ‘will be remembered as a choreographer with a superb sense of theatre and a gift for creating comedy character dancing unrivalled by any of his contemporaries… Relaxed and cheerful, he was always with his dancers – in the studio, the canteen, the bar, the cafe. It was this easy camaraderie that made the Stuttgart Ballet such a happy company and will give it, now, the will to endure.’

Born in South Africa in 1927, Cranko grew up with a love of puppets, the theatre and dance. Encouraged by his parents, who told him stories about the performances they saw by Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Cranko took up ballet lessons with the ultimate ambition of becoming a choreographer. He trained with Dulcie Howes at the University of Cape Town Ballet School, where he created his first choreographic works, including an ambitious version of Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale.

Realising that to advance his career he would need to leave the country, he travelled to London to study at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School. Cranko was not a remarkable dancer, but he entered Sadler’s Wells (later Royal) Ballet in 1947, where director Ninette de Valois quickly spotted his talent for choreography.

‘Cranko combined the precious gifts of the choreographic artist with a human warmth and concern for his dancers’

Malve Gradinger

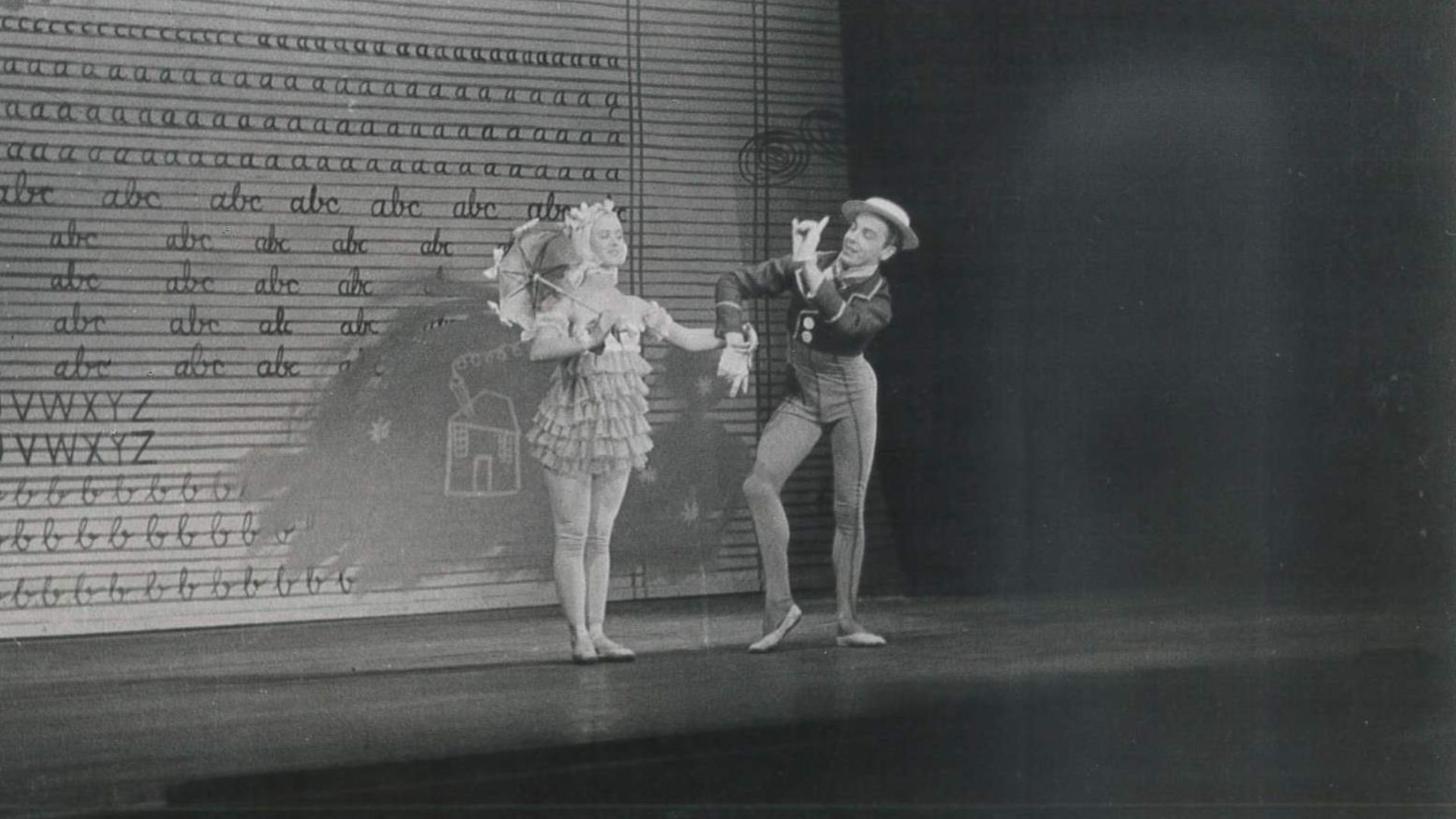

That year, Cranko created Morceaux Enfantins for the RAD Production Club, which proved so successful it was taken into the repertoire of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet as Children’s Corner. Thereafter, and with growing confidence and facility, Cranko continued to make successful ballets, most notably Pineapple Poll and The Lady and the Fool. He had a flair for comedy and, although he revered the choreography of George Balanchine, Cranko was most interested in creating dance works primarily about people. He collaborated with artists such as John Piper and Osbert Lancaster, worked closely with composer Benjamin Britten on The Prince of the Pagodas, and was seen as a natural successor to choreographer Frederick Ashton at the Royal Ballet.

Cranko also worked in the theatre, most famously on the revue Cranks, but after he was prosecuted for homosexual activity in 1959 (still a criminal offence then), job offers in Britain seemed to dry up, which was why he ultimately took up the position of ballet director in Stuttgart. There, according to Malve Gradinger, Cranko ‘developed into a director of genius… In later years it became more and more apparent that Cranko combined the precious gifts of the choreographic artist with a human warmth and concern for his dancers.’

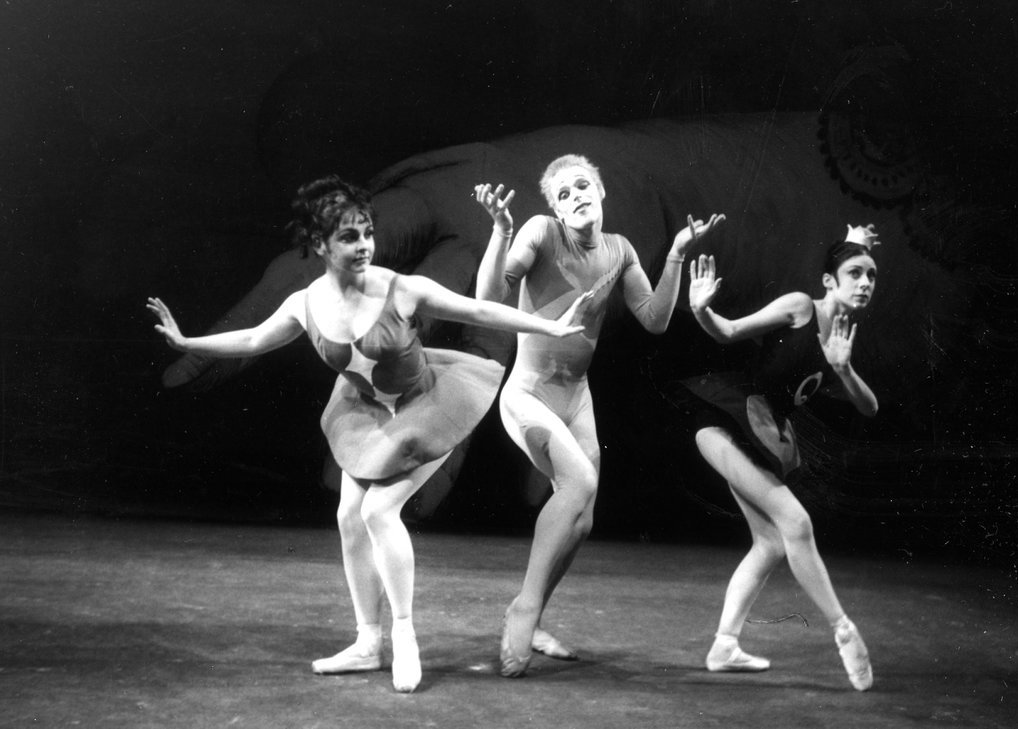

He expanded Stuttgart’s repertoire with stagings of Romeo and Juliet, Onegin and The Taming of the Shrew, as well as many interesting one-act works, discovered a ballerina in Marcia Haydée, championed dancers such as Ray Barra, Richard Cragun, Susanne Hanke, Birgit Keil, Heinz Klaus and Egon Madsen, and encouraged choreography from Jirí Kylián, John Neumeier and Peter Wright. This all culminated in the company’s triumphant seasons at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, where it was acclaimed as the ‘Stuttgart miracle’.

Why was Cranko such an exceptional man? Ninette de Valois, founder of the Royal Ballet, believed, ‘The mind of Cranko was always alert, individual and independent; yet he was genuinely receptive.’ Cranko’s friend, art critic and librettist Myfanwy Piper, said he ‘never stopped looking, listening and absorbing…’ and those who met him ‘were exhilarated by his ardour, his generosity and his receptiveness… He knew how to extract ideas and information from people without making them feel sucked of vitality – because he never failed to give as much as he took.’

Cranko encouraged the people with whom he worked. In Barbara Newman’s Antoinette Sibley: Reflections of a Ballerina, the former Royal Academy of Dance president said it was Cranko who ‘gave me the chance to prove myself. Well, how grateful can one be to that first person who has chosen you so other people can see what you can make out of a role? …he gave me such courage.’ In her autobiography, Lynn Seymour vividly described a man who ‘had a remarkable gift of language. He articulated what he wanted from his dancers with a vibrant Oscar Wildean wit. Words flowed easily, his thoughts were communicated briskly, precisely, with a razor-sharp clarity. No mutters, stutters, murmurs or mumbles.’

The choreographer had the knack of bringing out the best in a dancer. Brenda Last, a former Royal Ballet principal, recalls, ‘I think I was the last person John rehearsed in Pineapple Poll, as it was just before he went to America on that last trip… John watched me dance the whole thing, and then at the end he got up, put his arm around my shoulders and said, “I really enjoyed that!” I thought that was just so extraordinary. He was very sweet.’

‘He loved people who were creative.

Reid Anderson

There were no rules’

Reid Anderson recounts how, after anxiously listing his insecurities to Cranko in the canteen one day, Cranko replied, ‘”That’s exactly what I like about you!” It was a turning point for me – I realised all of that didn’t matter to him at all. What mattered was who you became on stage. He loved people who were creative. He was looking for faces, for people who had ‘it’. You either had “it” or you didn’t. There were no rules. He knew Marcia [Haydée] would be his ballerina – she had “it” and she was absolutely fearless.’

‘I think he needed to see a thirst for advancement but real humility [in a dancer],’ says Ashley Killar, former Stuttgart dancer and Cranko’s biographer. ‘John wanted to work with people who wanted to work with him,’ adds RAD vice-president, Monica Mason, who performed in Cranko’s ballets when she was a member of the Royal Ballet. ‘Stuttgart Ballet were his “followers” – he invested so much emotion into people in the same kind of way Kenneth MacMillan did. Ashton was different – he was inclined to be lyrical and romantic – but John and Kenneth were much more realistic in outlook. They lived in the real world, but they also minded about technique.’

To this day, dancers enjoy appearing in Cranko’s creations. ‘I loved performing them, especially Pineapple Poll, as they were a real company effort and had lots of characterisation,’ enthuses Iain Mackay, former principal with Birmingham Royal Ballet. ‘There were always lots of good roles, and they were great fun, but they were bloody hard to perform! With Captain Belaye in Poll, his solo is fiendish – it requires such precision. And in Shrew, those pas de deux for Kate and Petruchio are so tricky – they were always a real challenge.’

Despite his achievements, Cranko never settled down in a happy, long-term relationship. Openly gay, I wondered if Cranko was lonely? ‘Desperately so,’ confirms Killar. ‘He was lonely, but he was also a loner,’ reveals Anderson. ‘He spent all day with the ballet company. In a way, I don’t think he was a person you could have had a relationship with – I don’t think his mind ever left his calling.’

Did the way Cranko worked as a director influence his dancers when they themselves became directors of dance companies? ‘Oh, God! Yes!’ exclaims Anderson. ‘Absolutely!’ replies Killar, ‘but an understanding with one’s administrator is vital. Cranko was inordinately fortunate in being employed by former playwright Erich Walter Schäfer, the Intendant at Stuttgart. Cranko’s habit of asking his dancers to explore a world outside themselves pays amazing dividends.’

As the anniversary of Cranko’s death approaches, Stuttgart Ballet will be presenting a gala tribute to him in June 2023, and is also involved in the making of a feature film on Cranko’s life, and that of his dancers. ‘John made us all feel like human beings – it was all about you and how you could “be” on stage,’ Reid Anderson concludes. ‘You were part of the family.’

Ashley Killar’s Cranko, The Man and His Choreography is published by Matador.

WATCH

Scenes from Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet and Pineapple Poll

Jonathan Gray was editor of Dancing Times from 2008 until 2022. He has also contributed to the Financial Times and Guardian, and is now a freelance dance writer.